Letter from Marabá

by Francis McDonagh 20th January 2012

The first settlers in Brazil clung to the beaches like crabs, said the 17th-century historian Frei Vicente do Salvador. The remark is often quoted, but it is a good description of the next part of my journey, from Recife to Natal and Fortaleza and then to Belém. In my case the crabwise journey was dictated by the availability of flights on my airpass.

Belém, of course, is at the mouth of the Amazon, and the river was the one thing (apart from scattered strips of light) that loomed up out of the night as our plane made its descent in Belém. Again on take-off, the high-rises in Belém looked like matchboxes beside the river, and as one walks through the city the river is a huge presence: while I was there an ocean-going ship turned on its axis far in the distance, hardly noticeable. I didn’t have time to try more than one exotic juice – bacuri – in Ver-o Peso market, and I did no more than photograph some very explosive-looking peppers. I would have liked to see more of the architecture left from the rubber boom, so I shall just have to go back.

Brazil nut treeMy next stop was Marabá, en route for Xinguara, in south-east Pará, to visit an old friend, French Dominican friar Henri des Roziers, who has worked for the Catholic Church’s Pastoral Land Commission in this region for over 30 years. Now almost 82, he has just returned from a year of medical treatment in France, having been given the choice by his French doctors of living longer in France or more happily in Brazil.

Brazil nut treeMy next stop was Marabá, en route for Xinguara, in south-east Pará, to visit an old friend, French Dominican friar Henri des Roziers, who has worked for the Catholic Church’s Pastoral Land Commission in this region for over 30 years. Now almost 82, he has just returned from a year of medical treatment in France, having been given the choice by his French doctors of living longer in France or more happily in Brazil.

Take-off from Belém for Marabá brings the traveller up against the modern Amazon. Expanses of rainforest soon disappear to be replaced by ranches scattered with patches of reddish-brown earth. My instructions are to take a minibus from the ‘old bus station’ in Marabá, which turns out to involve a 90-minute wait until there are enough passengers. The roll-call of the minibus destinations is a roll-call of economic expansion in this area over the last 50 years, Tucuruí, Parauapebas, Açailândia. Finally we pack into the bus and thread our way through Marabá, making a final stop at what is presumably the new bus station, before setting out on to the main road to Xinguara.

Any hope that we will cover the 250-odd kilometres to Xinguara in a nippy four hours is dashed as the rain sets in and the minibusstarts a regular jolting over pot-holes, but conversation gets going and I learn several life stories, usually about breakdowns in relationships or buying a piece of land only to find after an absence that it has been sold again to someone else, who is building a house and planting crops. The victim in this case seemed remarkably open to negotiate, though the terms seemed stiff: ‘You can plant, but you can’t have the crop.’ I never did find out exactly how the story ended, but it seemed an appropriate introduction to the region and its issues. My mobile had no coverage, and I was cursing myself for not updating my hosts on my progress before leaving Marabá, so I trusted on my experience that things usually worked out in these sorts of arrangements.

I was heartened when I gave the address to the taxi-driver at Xinguara’s bus station. ‘Frei Henrique’s house?’ he asked. And when I finally banged on the door and clapped my hands, no-one seemed that surprised to see me. Frei Henri explained that he’d not been quite sure whether I was coming that day or the previous day. I confirmed my bona fides by handing over a bottle of malt whisky that had been the subject of much conversation in the previous weeks, and which replaced one I’d given to Henri in Paris a few months before and which hadn’t got past Henri’s Dominican brothers in São Paulo. Most Dominicans I know I have good taste in drink; that probably has something to do with their motto, ‘Truth’ – accept no substitutes!

Not much whisky was drunk that night, but I was revived with a nourishing soup, and gladly retired.

The next day is my introduction to Pará and land issues. Henri has to go to the court at Redenção, the capital of the ranchers in this area, to lodge a complaint that he and the CPT think may show that many titles to estates in this part of the country are invalid. He doesn’t want to go into too much detail, but the journey and the conversation take us to the heart of the land conflict. This region was deforested about 20 years ago, and on our journey Henri points to a road sign for ‘Bannach’. Bannach, he says, was a family from Paraná in the south of Brazil that bought land in the area and then felled all the trees for timber. With all the timber gone, they started in ranching. The story is typical.

The MST encampmentOn our way we pass a turn-off to Floresta do Araguaia, and one of the reasons for the potholes becomes clear. There is an iron-ore mine at this town on the Araguaia river, and the truck and trailer units that rumble south from here to Marabá take their toll on the asphalt. The other main freight is cattle. At one point cattle were trucked to Belém for shipment live to the Middle East, apparently a lucrative trade, but I am told that it has been suspended because of objections to the insanitary conditions. Our driver comments bitterly about the state of the roads in the region. His names for the Trans-Amazonian highway are ‘Trans-Pothole’ and ‘Trans-Agony’. It’s odd that in a region apparently important for Brazil’s exports the infrastructure is so poor.

The MST encampmentOn our way we pass a turn-off to Floresta do Araguaia, and one of the reasons for the potholes becomes clear. There is an iron-ore mine at this town on the Araguaia river, and the truck and trailer units that rumble south from here to Marabá take their toll on the asphalt. The other main freight is cattle. At one point cattle were trucked to Belém for shipment live to the Middle East, apparently a lucrative trade, but I am told that it has been suspended because of objections to the insanitary conditions. Our driver comments bitterly about the state of the roads in the region. His names for the Trans-Amazonian highway are ‘Trans-Pothole’ and ‘Trans-Agony’. It’s odd that in a region apparently important for Brazil’s exports the infrastructure is so poor.

Before leaving Redenção, we call in one of the mobile phone shops. Apparently Henri’s usage entitles him to two free (almost free – I think he pays the equivalent of US$25) mobiles, which he has decided to give to the young admin assistant at the CPT and to the woman who cooks and cleans in his house. I spend some time helping the assistant with his choice – the variety on offer looks as good as in a British small town. As we wait the shop fills up, but it turns out to be mainly people coming in to get print-outs of their bills and pay. Digital payments don’t seem to be common here.

Over the next couple of days I’m filled in on the current concerns of the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT). It was set up by the Catholic Church at the height of the Brazilian military dictatorship, in 1975, with an initial brief to support the small farmers who had occupied land in the Amazon region, either before or in the wake of the official push to exploit the region. Under Brazilian law these squatters acquired rights if they occupied land for a year and a day, but the government-backed businesses moving into the region had no time for such niceties, and the list of union leaders, priests and nuns killed in the defence of poor farmers is a long one. In addition to famous names such as Chico Mendes, the CPT has its own martyrs, the priest Josimo Tavares, murdered in 1986, two local union leaders from the south of Pará, João Canuto (1985) and Expedito Ribeiro de Souza (1991), down to American religious Sister Dorothy Strang (2005) and the environmental activists José Claudio Ribeiro da Silva and his wife Maria do Espírito Santo in May 2011.

Little has changed, according to Henri and his colleague Aninha Souza Pint. A pair of young men from a squatter camp were ambushed a few months ago, and one killed, they tell me. ‘It was very difficult for the Landless Movement (MST) to establish itself in this region,’ they tell me. Nevertheless, the MST is here, and one nearby encampment is named after the murdered João Canuto. As we drive past it a few days later, people of all ages wave and shout greetings to Henri. ‘The MST is a key partner for the CPT,’ he tells me. They are well organised, they do educational work and they have political vision.’

Something of that vision comes across later when I attend a meeting between the CPT and leaders from the local MST encampment called to prepare for a negotiating meeting a few days later with INCRA, the land reform agency, and representatives of the landowner whose land they have occupied. The MST leaders have not only a Plan A, but Plans B, C and D. Their aim is to challenge the rights of the companies who occupy the huge estates – a million hectares, in one case, I’m told – either because the land is not productive (which makes them vulnerable to expropriation under Brazilian law) or, and this is the CPT’s suspicion, because the land titles on which they base their claims are invalid.

In that sense, the CPT’s role has changed little in the last 47 years, except that they came to understand the different situations of indigenous people and the demands of sustainability in this region. Their current challenge is to widen their vision to include the mining industry that is now well established in this region. Nevertheless the pastoral dimension of their work is still important: they encourage the MST to make sure their decisions are really discussed and supported by the people. The CPT’s origins in liberation theology, and its experience with authoritarian Church structures, give it useful experience here.

That experience may be needed again within the Church. Henri says that the current bishop, also French, is trying to re-establish a more traditional Church, with an emphasis on clerical dress. Because of his status Henri gives the local CPT some protection, but there is concern about what will happen when he can no longer continue his role. There are fond recollections of the previous bishop, Joe (Dom José) Hanrahan, who was firm in his support for the poor farmers, whose hardships were familiar to him from his Irish childhood. Support from authority figures like a bishop can be a matter of life and death for activists in places like Xinguara. Before he left for France at the end of 2010, Henri had police bodyguards who travelled everywhere with him – one slept inside the front door of his house. Now he thinks he doesn’t need this protection; he now has more of a back-seat role and won’t be so prominent. This view wasn’t shared by one of his former bodyguards who came round with his baker wife to bring Henri a cake: ‘There are some nasty pieces of work in the local police,’ he whispered to me as he left.

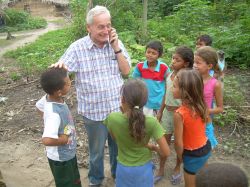

Friar Henri with children from the campBrazilians call this region the ‘Wild West’ (o faroeste), almost another country. And yet it is part of the new Brazil. Marabá is the railhead of the iron-ore trains of Vale, the once state-owned mining company now a multi-national and said to be the world’s biggest mining company with a presence in 38 countries. Many of the ranches in the area between Xinguara and Marabá are owned by the Santa Bárbara company, said by the CPT team to be the owner of the world’s second largest cattle herd. One of the shareholders in Santa Bárbara is the controversial banker Daniel Dantas. Another link with power is the frequent presence at cattle auctions here of Lula’s public relations chief, Dudu Mendonça. These contrasts come together as I leave Xinguara for Marabá in the down-market Volkswagen belonging to the CPT’s young lawyer, Nilson. We are taking Henri for a flight to São Paulo for the annual meeting of Brazil’s Dominicans, but the following day Nilson will face the Santa Bárbara lawyer from São Paulo in the negotiation on behalf of the MST.

Friar Henri with children from the campBrazilians call this region the ‘Wild West’ (o faroeste), almost another country. And yet it is part of the new Brazil. Marabá is the railhead of the iron-ore trains of Vale, the once state-owned mining company now a multi-national and said to be the world’s biggest mining company with a presence in 38 countries. Many of the ranches in the area between Xinguara and Marabá are owned by the Santa Bárbara company, said by the CPT team to be the owner of the world’s second largest cattle herd. One of the shareholders in Santa Bárbara is the controversial banker Daniel Dantas. Another link with power is the frequent presence at cattle auctions here of Lula’s public relations chief, Dudu Mendonça. These contrasts come together as I leave Xinguara for Marabá in the down-market Volkswagen belonging to the CPT’s young lawyer, Nilson. We are taking Henri for a flight to São Paulo for the annual meeting of Brazil’s Dominicans, but the following day Nilson will face the Santa Bárbara lawyer from São Paulo in the negotiation on behalf of the MST.

Henri makes his flight and we go on to our accommodation, which turns out to be an extremely dilapidated Church hostel-cum-training centre. ‘Rogues alley’, a taxi-driver calls the address, as we try to negotiate a lift for me the following morning. As we lie in our bunks looking at the cobwebs threatening to drop on to Nilson’s court suit hanging on the wall and listening to the toads, I remember many similar places, homes to similar struggles. Despite two terms of PT government, the struggle doesn’t seem to have got more equal.