São Paulo, 1 February: Election day is still eight months away, but Brazil’s presidential election campaign is in full swing.

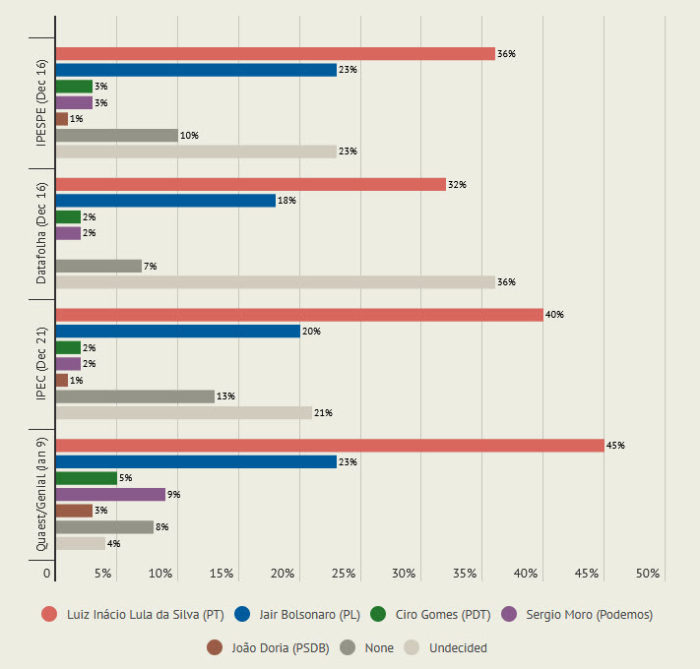

Poll after poll shows Lula, the Workers’ Party (PT) candidate, leading by a large margin, over 20 points ahead of President Jair Bolsonaro who is standing for re-election as candidate for the rightwing Liberal Party (PL). No other candidate has yet reached double figures.

Desperate efforts to find a moderate, the so called ‘Third Way’, have so far failed. Conservative sectors had high hopes that Sergio Moro would fit the bill and the establishment press have given him ample, favourable coverage. But the former judge, notorious for his harsh sentences condemning Lula and other PT leaders for corruption, before becoming minister of Justice in Bolsonaro’s government, has failed to impress.

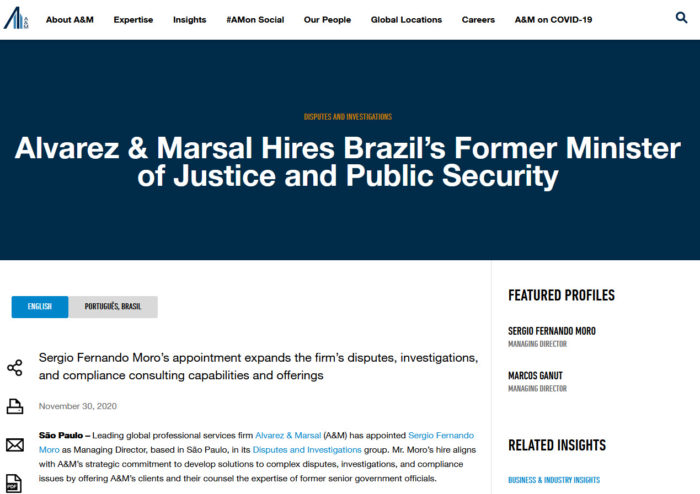

It is not just his wooden speeches and lack of charisma, but the revelation that he was paid almost 4 million dollars as a ‘consultant’ by the American firm Alvarez & Marsal, chosen to administer the financial recovery of Brazil’s major construction firms after they were destroyed by the anti-corruption crusade known as Lava Jato. This crusade was led by Moro and a handful of public prosecutors imbued with a McCarthyite spirit of persecution. Almost all of Lula’s convictions have now been overturned by higher courts, and Moro himself has been judged by the Supreme Court to have acted in these cases without impartiality.

The conservative press likes to present the election as a choice between political extremes, but it promises to be a contest between a far right populist and a broad front of parties who believe in democracy. While Bolsonaro has shown himself to be a neofascist who eulogises the military dictatorship and disdains civil society, Lula has been busy building a wide alliance of left, centre and centre-right parties. He wants Geraldo Alkmin, former governor of São Paulo for the social democrat party (PSDB) as his vice-presidential running mate, repeating the formula that brought him victory in 2002 when conservative businessman José Alencar was chosen for that role.

The threat of violence

Many fear that this will be an election marred by violence, encouraged by anti-communist rhetoric and incitement of hate crimes against certain groups. Researchers have noted the rapid growth of neo-Nazi groups, especially in the south of Brazil. The election of a sizeable number of gay, trans and black councillors in the 2020 local elections led to many of them becoming the target for hate attacks.

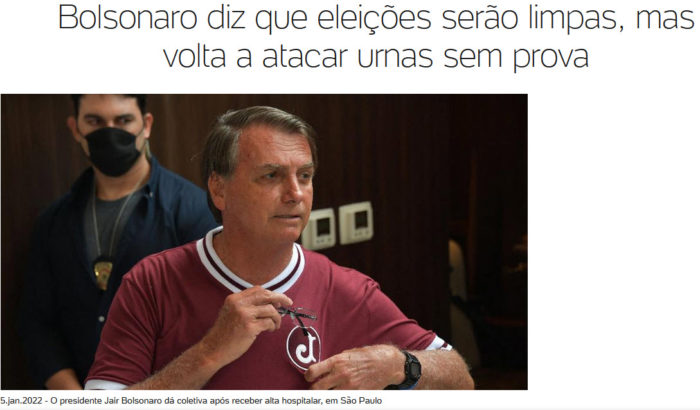

There is concern also about the increasing number of guns now circulating in Brazil, thanks to Bolsonaro’s continuous efforts to weaken gun control and undermine the Disarmament Statute, passed in 2003 after a plebiscite. Thousands of heavy arms have been imported into Brazil during this government, ostensibly destined for hunters and collectors, but with no control over their final destination. Not just violence during the campaign is feared, but if Lula wins, a US-like Capitol attack. For months Bolsonaro has been deliberately trying to undermine belief in the voting system, falsely claiming that the ‘electronic urns’ – a system which Brazil has exported to many countries – are open to fraud.

Doubt about the position of the armed forces in the event of a Lula victory also fed into this scenario. Would they accept Bolsonaro’s defeat? The commander of the Air Force has thrown a large bucket of cold water on these fears by letting it be known that he would ‘salute whoever wins’, but it is an indication of the apparent fragility of Brazil’s democracy that military commanders are front page news when they state the obvious.

If Lula wins…

The task facing Lula, if he wins, is daunting. Not only will he inherit a country devastated by Covid, with well over 600,000 deaths, including several hundred children, but he will also inherit a government machine which in many sectors has been deliberately destroyed by ideological bias, incompetence and corruption.

Thousands of unprepared military and retired police officers have been given well paid jobs in ministries, ousting experienced staff. Resources for education, health, research, science, environmental monitoring and enforcement, forest firefighting, indigenous health and traditional populations have been cut, but funding has been lavished on pro-Bolsonaro politicians.

The social advances achieved under PT governments – millions moving out of extreme poverty and thousands of black and socially disadvantaged students being able to go to university thanks to quotas and grants – have been undone by Bolsonaro, whose priorities are the uniformed forces and getting re-elected at any cost.

A huge increase in hunger and homelessness is the Bolsonaro legacy. Emergency aid to compensate the millions left jobless by the pandemic was sporadic and ill-targeted. It is reckoned that a quarter of the Brazilian population is going hungry. Scenes of people fighting over bones outside butcher’s shops have become common. The streets of São Paulo are lined with miserable makeshift camps and tents where entire families now live, unable to afford rent without jobs or welfare payments. The homeless population in Brazil’s largest city has grown by over 30 per cent during the pandemic.

The ‘Centre’ is rotten

Meanwhile funds for pro-Bolsonaro politicians are abundant. O Globo newspaper says that the Centrão, the alliance of right-wing parties which provides Bolsonaro with his political support, now controls most of the government budget, and is getting more money than the big-spending ministries of education and defense.

The three parties which make up the Centrao, the PP, the PL and Republicanos, occupy 32 key posts in the government, including that of the president’s chief of staff. Large sums are channelled through Congress to selected representatives, in what has become known as the ‘secret budget’, in exchange for their support in passing Bolsonaro projects and barring the many impeachment attempts.

However the Centrão is notoriously fickle. Few doubt that if Lula manages to build an ample alliance which includes not only political parties and movements of the left and centre-left but also the non-fascist right, and continues to lead the polls, then they will jump ship, leaving Bolsonaro to sink alone after pocketing his bribes. This will be at the same time a boost and a problem for Lula, saddled with sating the greed of these politicians for jobs and funds, the very situation that led to the Mensalão scandal in his second presidency.

… and Bolsonaro, if he loses

The elephant in the room is Bolsonaro himself. If he loses, will he go quietly? Or will he imitate his mentor Trump and call foul? Trump advisers are said to be working with the Brazilian president on his election campaign. For the far right Bolsonaro’s victory is vital to stop the advance of the left in South America, after the ‘fall’ of Chile.

The election is a straight fight between two diametrically opposed projects for Brazil. Bolsonaro promises more poverty, more discrimination, more hatred, more Amazon destruction, less education and health, a continuation of Brazil’s pariah status in the world. Lula offers less inequality, more social justice, a huge development programme and a return to Brazil’s status as a world power.

What is also at stake is not only the future of one of the world’s largest countries, but possibly the future of the world, because of the vital role in climate change played by Brazil’s Amazon rainforest. If Bolsonaro is re-elected, the Amazon, already suffering the worst destruction in decades on his watch, will be doomed. If Lula wins, there is at least a chance that it can be saved.

Main image: from PT official website