In 2000, as the new millennium created new expectations, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the PRI, lost power after running Mexico for 71 years, from the time of the revolution. During its tenure, the PRI created a vast network of corruption and nepotism that came to an end when the party finally decided to democratise Mexico’s political structure and to compete on equal terms with the main opposition party, the Party of National Action, PAN. It lost. Twice. A year and a half ago, after two disastrous PAN presidencies (Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón), the PRI came back with a vengeance.

Its leader, Enrique Peña Nieto, a politician with the manners of a bank manager and a poor grasp of the country’s basic structure (on one occasion he could not name all the states that form Mexico), became the come-back boy of his party. His main argument was simple: the PRI was no longer the party of corrupt politicians and “clientelismo” ( which meant favouring a party member for a public works contract or for a job in the state bureaucracy) but an organisation that had learned the lessons of the past. It would be the party of economic growth, friendly with the entrepreneurial class that would elevate Mexico to the pinnacle of the global economy.

One year and a half later, I interviewed two very different Mexicans. Both had nourished some hopes of the new PRI, but now their patience is wearing thin.

Sergio is a very disappointed man. He is a filmmaker, a man who in the past has produced videos for many companies. During the recession years, work drained away and life was difficult. So, when Luis Peña Nieto spoke in his campaign of economic growth and of promoting private initiatives, he thought that indeed the PRI was different today and that people like him, a self-employed cameraman, would benefit from the new wave of investments and profitable companies.

But things have soured. The economy in Mexico is stagnant. Peña Nieto’s promises of 6% annual growth have given way to a more modest estimate: 2.7%. Sergio has not seen a surge in his business. Income tax has increased and the National Association of Self-service and Department Stores has reported the biggest slump of sales in 30 years. Sergio is still waiting for the Peña Nieto miracle.

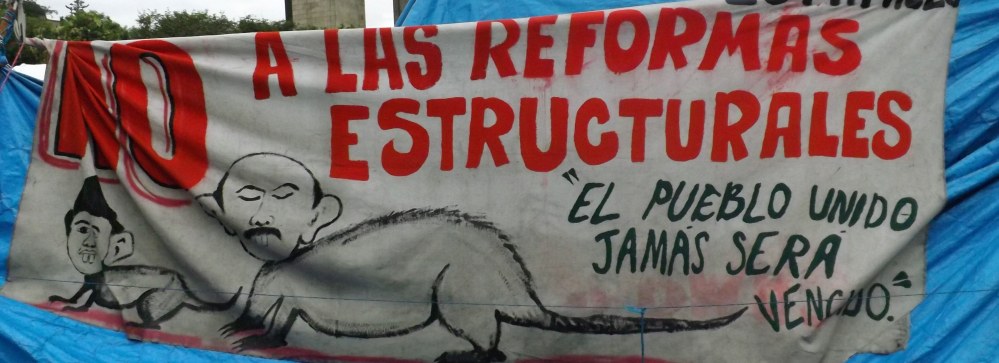

So is Luis, a teacher from Oaxaca who is camping behind the Monument of the Revolution, in downtown Mexico City. He belongs to the National Coordination of Education Workers, a teachers’ union created in 1979 as an alternative to the National Union of Education Workers, whose leader, Elba Ester Gordillo, is serving time for corruption. Luis comes from Oaxaca, where the teachers have been protesting against the so-called ‘education reform’. When Peña Nieto took office, he promised to improve the quality of the education system. However, the teachers’ union was dismayed when it realised that the new law did not include a single paragraph about reforming the way children and indeed university students are educated. “This is an administrative law, not a reform”, says Luis, while he and his comrades try to pour off the water from the top of their plastic tent as a storm threatens to destroy the place that has become their home.

The new education law requires teachers to take stiff exams. If they don’t pass the test the first time, they will be relegated to administrative duties. If they don’t pass the test a second time, they are out. Trouble is, says Luis – and his comrades nod in agreement – that in some poor states, like Oaxaca, in southwest Mexico, one teacher is responsible for four grades. Schools do not have the means to maintain their classrooms and sometimes children are too poor to attend. “How is testing teachers going to solve this problem?” asks Luis. Many teachers have been on strike for some months now and the government does not seem to be able to start a dialogue to hear their demands.

Sergio and Luis come from completely different trades. Sergio is an entrepreneur and Luis is a public servant, a teacher. They are not unhappy with the PRI because it has gone back to its old corrupt tricks. In fact, they both admit that the “new” PRI is not as corrupt as the ”old” one. Peña Nieto has learned the lesson. He and his party know that, if they are seen as the traditional party of cronyism, they will be out in the next election. However, the new proposals that made them electable again have not been fulfilled. Peña Nieto seems to have alienated people from both the left and the right. There is a link between Sergio and Luis: for as long economic growth remains elusive, the resources available to improve the standards of education in the country will be in short supply, and many teachers will be in danger of losing their jobs. Time may not be running out yet for Peña Nieto but it seems that people’s patience is beginning to be stretched.

In 2000, as the new millennium created new expectations, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the PRI, lost power after running Mexico for 71 years, from the time of the revolution. During its tenure, the PRI created a vast network of corruption and nepotism that came to an end when the party finally decided to democratise Mexico’s political structure and to compete on equal terms with the main opposition party, the Party of National Action, PAN. It lost. Twice. A year and a half ago, after two disastrous PAN presidencies (Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón), the PRI came back with a vengeance.

Its leader, Enrique Peña Nieto, a politician with the manners of a bank manager and a poor grasp of the country’s basic structure (on one occasion he could not name all the states that form Mexico), became the come-back boy of his party. His main argument was simple: the PRI was no longer the party of corrupt politicians and “clientelismo” ( which meant favouring a party member for a public works contract or for a job in the state bureaucracy) but an organisation that had learned the lessons of the past. It would be the party of economic growth, friendly with the entrepreneurial class that would elevate Mexico to the pinnacle of the global economy.

One year and a half later, I interviewed two very different Mexicans. Both had nourished some hopes of the new PRI, but now their patience is wearing thin.

Sergio is a very disappointed man. He is a filmmaker, a man who in the past has produced videos for many companies. During the recession years, work drained away and life was difficult. So, when Luis Peña Nieto spoke in his campaign of economic growth and of promoting private initiatives, he thought that indeed the PRI was different today and that people like him, a self-employed cameraman, would benefit from the new wave of investments and profitable companies.

But things have soured. The economy in Mexico is stagnant. Peña Nieto’s promises of 6% annual growth have given way to a more modest estimate: 2.7%. Sergio has not seen a surge in his business. Income tax has increased and the National Association of Self-service and Department Stores has reported the biggest slump of sales in 30 years. Sergio is still waiting for the Peña Nieto miracle.

So is Luis, a teacher from Oaxaca who is camping behind the Monument of the Revolution, in downtown Mexico City. He belongs to the National Coordination of Education Workers, a teachers’ union created in 1979 as an alternative to the National Union of Education Workers, whose leader, Elba Ester Gordillo, is serving time for corruption. Luis comes from Oaxaca, where the teachers have been protesting against the so-called ‘education reform’. When Peña Nieto took office, he promised to improve the quality of the education system. However, the teachers’ union was dismayed when it realised that the new law did not include a single paragraph about reforming the way children and indeed university students are educated. “This is an administrative law, not a reform”, says Luis, while he and his comrades try to pour off the water from the top of their plastic tent as a storm threatens to destroy the place that has become their home.

The new education law requires teachers to take stiff exams. If they don’t pass the test the first time, they will be relegated to administrative duties. If they don’t pass the test a second time, they are out. Trouble is, says Luis – and his comrades nod in agreement – that in some poor states, like Oaxaca, in southwest Mexico, one teacher is responsible for four grades. Schools do not have the means to maintain their classrooms and sometimes children are too poor to attend. “How is testing teachers going to solve this problem?” asks Luis. Many teachers have been on strike for some months now and the government does not seem to be able to start a dialogue to hear their demands.

Sergio and Luis come from completely different trades. Sergio is an entrepreneur and Luis is a public servant, a teacher. They are not unhappy with the PRI because it has gone back to its old corrupt tricks. In fact, they both admit that the “new” PRI is not as corrupt as the ”old” one. Peña Nieto has learned the lesson. He and his party know that, if they are seen as the traditional party of cronyism, they will be out in the next election. However, the new proposals that made them electable again have not been fulfilled. Peña Nieto seems to have alienated people from both the left and the right. There is a link between Sergio and Luis: for as long economic growth remains elusive, the resources available to improve the standards of education in the country will be in short supply, and many teachers will be in danger of losing their jobs. Time may not be running out yet for Peña Nieto but it seems that people’s patience is beginning to be stretched.

Mexico: Is the “new” PRI worse than the “old” one?

In 2000, as the new millennium created new expectations, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the PRI, lost power after running Mexico for 71 years, from the time of the revolution. During its tenure, the PRI created a vast network of corruption and nepotism that came to an end when the party finally decided to democratise Mexico’s political structure and to compete on equal terms with the main opposition party, the Party of National Action, PAN. It lost. Twice. A year and a half ago, after two disastrous PAN presidencies (Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón), the PRI came back with a vengeance.

Its leader, Enrique Peña Nieto, a politician with the manners of a bank manager and a poor grasp of the country’s basic structure (on one occasion he could not name all the states that form Mexico), became the come-back boy of his party. His main argument was simple: the PRI was no longer the party of corrupt politicians and “clientelismo” ( which meant favouring a party member for a public works contract or for a job in the state bureaucracy) but an organisation that had learned the lessons of the past. It would be the party of economic growth, friendly with the entrepreneurial class that would elevate Mexico to the pinnacle of the global economy.

One year and a half later, I interviewed two very different Mexicans. Both had nourished some hopes of the new PRI, but now their patience is wearing thin.

Sergio is a very disappointed man. He is a filmmaker, a man who in the past has produced videos for many companies. During the recession years, work drained away and life was difficult. So, when Luis Peña Nieto spoke in his campaign of economic growth and of promoting private initiatives, he thought that indeed the PRI was different today and that people like him, a self-employed cameraman, would benefit from the new wave of investments and profitable companies.

But things have soured. The economy in Mexico is stagnant. Peña Nieto’s promises of 6% annual growth have given way to a more modest estimate: 2.7%. Sergio has not seen a surge in his business. Income tax has increased and the National Association of Self-service and Department Stores has reported the biggest slump of sales in 30 years. Sergio is still waiting for the Peña Nieto miracle.

So is Luis, a teacher from Oaxaca who is camping behind the Monument of the Revolution, in downtown Mexico City. He belongs to the National Coordination of Education Workers, a teachers’ union created in 1979 as an alternative to the National Union of Education Workers, whose leader, Elba Ester Gordillo, is serving time for corruption. Luis comes from Oaxaca, where the teachers have been protesting against the so-called ‘education reform’. When Peña Nieto took office, he promised to improve the quality of the education system. However, the teachers’ union was dismayed when it realised that the new law did not include a single paragraph about reforming the way children and indeed university students are educated. “This is an administrative law, not a reform”, says Luis, while he and his comrades try to pour off the water from the top of their plastic tent as a storm threatens to destroy the place that has become their home.

The new education law requires teachers to take stiff exams. If they don’t pass the test the first time, they will be relegated to administrative duties. If they don’t pass the test a second time, they are out. Trouble is, says Luis – and his comrades nod in agreement – that in some poor states, like Oaxaca, in southwest Mexico, one teacher is responsible for four grades. Schools do not have the means to maintain their classrooms and sometimes children are too poor to attend. “How is testing teachers going to solve this problem?” asks Luis. Many teachers have been on strike for some months now and the government does not seem to be able to start a dialogue to hear their demands.

Sergio and Luis come from completely different trades. Sergio is an entrepreneur and Luis is a public servant, a teacher. They are not unhappy with the PRI because it has gone back to its old corrupt tricks. In fact, they both admit that the “new” PRI is not as corrupt as the ”old” one. Peña Nieto has learned the lesson. He and his party know that, if they are seen as the traditional party of cronyism, they will be out in the next election. However, the new proposals that made them electable again have not been fulfilled. Peña Nieto seems to have alienated people from both the left and the right. There is a link between Sergio and Luis: for as long economic growth remains elusive, the resources available to improve the standards of education in the country will be in short supply, and many teachers will be in danger of losing their jobs. Time may not be running out yet for Peña Nieto but it seems that people’s patience is beginning to be stretched.

In 2000, as the new millennium created new expectations, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the PRI, lost power after running Mexico for 71 years, from the time of the revolution. During its tenure, the PRI created a vast network of corruption and nepotism that came to an end when the party finally decided to democratise Mexico’s political structure and to compete on equal terms with the main opposition party, the Party of National Action, PAN. It lost. Twice. A year and a half ago, after two disastrous PAN presidencies (Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón), the PRI came back with a vengeance.

Its leader, Enrique Peña Nieto, a politician with the manners of a bank manager and a poor grasp of the country’s basic structure (on one occasion he could not name all the states that form Mexico), became the come-back boy of his party. His main argument was simple: the PRI was no longer the party of corrupt politicians and “clientelismo” ( which meant favouring a party member for a public works contract or for a job in the state bureaucracy) but an organisation that had learned the lessons of the past. It would be the party of economic growth, friendly with the entrepreneurial class that would elevate Mexico to the pinnacle of the global economy.

One year and a half later, I interviewed two very different Mexicans. Both had nourished some hopes of the new PRI, but now their patience is wearing thin.

Sergio is a very disappointed man. He is a filmmaker, a man who in the past has produced videos for many companies. During the recession years, work drained away and life was difficult. So, when Luis Peña Nieto spoke in his campaign of economic growth and of promoting private initiatives, he thought that indeed the PRI was different today and that people like him, a self-employed cameraman, would benefit from the new wave of investments and profitable companies.

But things have soured. The economy in Mexico is stagnant. Peña Nieto’s promises of 6% annual growth have given way to a more modest estimate: 2.7%. Sergio has not seen a surge in his business. Income tax has increased and the National Association of Self-service and Department Stores has reported the biggest slump of sales in 30 years. Sergio is still waiting for the Peña Nieto miracle.

So is Luis, a teacher from Oaxaca who is camping behind the Monument of the Revolution, in downtown Mexico City. He belongs to the National Coordination of Education Workers, a teachers’ union created in 1979 as an alternative to the National Union of Education Workers, whose leader, Elba Ester Gordillo, is serving time for corruption. Luis comes from Oaxaca, where the teachers have been protesting against the so-called ‘education reform’. When Peña Nieto took office, he promised to improve the quality of the education system. However, the teachers’ union was dismayed when it realised that the new law did not include a single paragraph about reforming the way children and indeed university students are educated. “This is an administrative law, not a reform”, says Luis, while he and his comrades try to pour off the water from the top of their plastic tent as a storm threatens to destroy the place that has become their home.

The new education law requires teachers to take stiff exams. If they don’t pass the test the first time, they will be relegated to administrative duties. If they don’t pass the test a second time, they are out. Trouble is, says Luis – and his comrades nod in agreement – that in some poor states, like Oaxaca, in southwest Mexico, one teacher is responsible for four grades. Schools do not have the means to maintain their classrooms and sometimes children are too poor to attend. “How is testing teachers going to solve this problem?” asks Luis. Many teachers have been on strike for some months now and the government does not seem to be able to start a dialogue to hear their demands.

Sergio and Luis come from completely different trades. Sergio is an entrepreneur and Luis is a public servant, a teacher. They are not unhappy with the PRI because it has gone back to its old corrupt tricks. In fact, they both admit that the “new” PRI is not as corrupt as the ”old” one. Peña Nieto has learned the lesson. He and his party know that, if they are seen as the traditional party of cronyism, they will be out in the next election. However, the new proposals that made them electable again have not been fulfilled. Peña Nieto seems to have alienated people from both the left and the right. There is a link between Sergio and Luis: for as long economic growth remains elusive, the resources available to improve the standards of education in the country will be in short supply, and many teachers will be in danger of losing their jobs. Time may not be running out yet for Peña Nieto but it seems that people’s patience is beginning to be stretched.