The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating toll in Latin America. It has left many important lessons that show vulnerabilities in the region’s preparedness for health emergencies. For the Indigenous communities in pre-pandemic Chiapas, Mexico, weak health systems and even weaker trust in authorities had dangerous consequences. The government’s mishandling of the pandemic and failure to include community input in mitigation plans exacerbated already low levels of trust. In turn, conspiracy theories spread rapidly, worsening the already low compliance of prevention measures. If Latin America is to be better prepared for future pandemics, cases like this will be a key piece in the puzzle of the vastly different needs and strategies.

If Latin America is to be better prepared for future pandemics, cases like this will be a key piece in the puzzle of the vastly different needs and strategies.

Disproportionate impacts

As elsewhere in Latin America, Indigenous peoples in Mexico faced disproportionately higher risks and negative impacts during and as a result of the pandemic. Some of the most frequently cited risk factors for Indigenous communities include the return of migrant workers to their home communities, limited access to clean water in rural villages and poor urban neighborhoods, overcrowded living conditions, reliance on working outside the home, lack of access to the Internet, and limited availability of updated public health information in Indigenous languages. In addition, health services in Indigenous-populated areas are often inadequate in coverage and quality which make early management of diseases more difficult, leading to greater risk of complications and fatalities.

However, Chiapas, lying on Mexico’s southern border with one of the highest Indigenous populations of all 32 states in Mexico (1.4 million of the state’s 5.5 million inhabitants) as well as the largest percentage of people living in poverty (75.5 per cent), has surprisingly low official figures for COVID-related infections and deaths.

By September 11, 2022 the official figures placed Chiapas as the state least affected by the pandemic, with 48,606 cases and 2,431 deaths, from a national total of 7.4 million cases and 344,000 deaths. In comparison, the neighboring states of Oaxaca and Tabasco respectively report three and four times as many cases of infection as in Chiapas, despite having lower overall populations (4.1 million in Oaxaca and 2.4 million in Tabasco). Both register more than double the number of deaths.

As a result of the seemingly low figures, the 4-colour traffic light system, used in Mexico since June 2020 to indicate the degree of risk from the pandemic and associated instructions, designated Chiapas ‘green light’ status in November 2020. It was only the second state in the country to enter the lowest-risk category, where it spent 48 weeks in 2021.

Undercounting and a “Green Light” for Chiapas

However, the rural and Indigenous population in Chiapas was not as protected as the green light suggests. Testimonies from several Indigenous communities in highland Chiapas suggest rising numbers of infections during the first four months of the pandemic. However, limited access to testing meant official data showed a much less severe situation with only 6,327 infections by August 27, 2020 (121 per 100,000) among the state’s total population of 5.5 million.

Likewise, there was also a marked increase in recorded burials by municipal authorities. For example, in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, there were around 170 recorded burials in May-June 2020 compared to just 30-35 in the same period in 2019. For the same comparative dates in the state capital, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the number of burials jumped from 180 in 2019 to 500 in 2020. In contrast, official COVID-19 figures suggest only 239 COVID-19 related deaths across the whole state by June 20, 2020.

Since the Health Ministry in Chiapas categorized deaths as COVID-related only when the deceased had tested positive at a regional hospital to which they had been admitted, the deaths of Indigenous people who died in their rural homes, unable to access to far away hospitals, do not appear in official COVID statistics, leading to a serious undercount across the region.

At the same time, the contradictory and slow response from federal government during the onset of the pandemic degraded already low levels of confidence in the truth of the pandemic and therefore also compliance with the measures in place.

Contagious conspiracy theories

Faced with the lack of a coherent public health strategy and reliable information from the government, conspiracy theories rapidly spread in many Indigenous communities. According to a survey of 1,000 people aged 15-18 in a marginalized area of Chiapas, a shocking 66 per cent of respondents believed in a conspiratorial origin to the pandemic.

Stories spread through WhatsApp and Facebook messages throughout Chiapas in the first few months of the pandemic, encouraging people to ransack local clinics and destroy government vehicles. The messages were sparked by a falsely subtitled video of Vladimir Putin that appeared to show him saying, in Russian, that he had discovered this evil plot and was exposing it to the world.

The precise origins of the conspiratorial WhatsApp messages is unknown but they tapped into theories that fed on people’s existing mistrust. For example, some messages claimed that the virus was being spread with the intention of reducing world overpopulation; that the Mexican government was under pressure from foreign powers to meet a quota of 60,000 deaths; that Mexican aircraft were dispersing the virus into the atmosphere above towns and villages of Chiapas where it would remain in the air for 36 hours in order to kill as many people as possible; or that fumigation by government officials was not to kill the virus but to spread deadly chemicals.

The messaging led to attacks on health clinics and staff fumigating against recurrent tropical diseases such as dengue and zika, and against agricultural extension workers spraying fruit trees to prevent infestations. It shows not only the depth of mistrust between communities and government but also the void in reliable information that was quickly filled.

Autonomous organization

Chiapas has a long history of mistrust, before the pandemic and traffic light systems came about. Discrimination, violence, and exploitation by more urban-based, non-Indigenous elite families referred to locally as la familia chiapaneca have been exposed by periodic revolts and social movements, most famously the armed uprising in 1994 of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), referred to simply as the Zapatistas. During the pandemic, the deep divide between la familia and the people became evident again.

Compared to the government’s confused and weak response to the pandemic, the Zapatistas implemented measures of prevention and temporarily isolated those community members who were returning from other parts of the country in their autonomously-governed communities, as was seen in other Indigenous areas in Mexico. They were also more prepared to respond to the pandemic due to their existing network of community health promoters whose approach is to ‘treat the person and not the disease.’

Declaring a ‘red alert‘ as early as March 16, 2020, the Zapatistas closed off their communities to non-members and recommended a series of steps to prevent the spread of infection in response to what they called the “the frivolous irresponsibility” and “lack of reliable and timely information” from the government. Such measures included the use of face coverings, social distancing, reduction of contact with urban populations, a 15-day quarantine for community members who may have been in contact with people infected by the virus, and the frequent washing of hands with soap and water.

Such measures helped to mitigate the impact of the pandemic in Zapatista communities, although at least 12 members of the organization had died due to the virus by October 2020. The Zapatistas took responsibility for not implementing even stronger measures that may have prevented these deaths.

In adopting preventative steps, the Zapatistas were able to count on the greater degree of trust in their own, autonomously selected community-level authorities, in contrast to the historic mistrust of most Indigenous communities toward the federal, state and municipal agencies of the Mexican government.

Responding to the pandemic’s disproportionate impacts

One of the lessons of the pandemic in Mexico has been the need for greater understanding in how different groups of the population have been impacted. Indigenous communities have remained mistrustful of state officials and the necessary steps for building preparedness, trust, and community involvement have not been taken, partly because of the discrimination that denies Indigenous people the right to equal participation in national life. In Chiapas, community mistrust was exacerbated by the lack of a clear and effective response from the government, the absence of reliable information, and the way that conspiracy theories quickly filled this gap. These issues of trust and involvement go beyond public health preparedness, but they must be addressed if the goal is to ensure a more just future for all Mexicans.

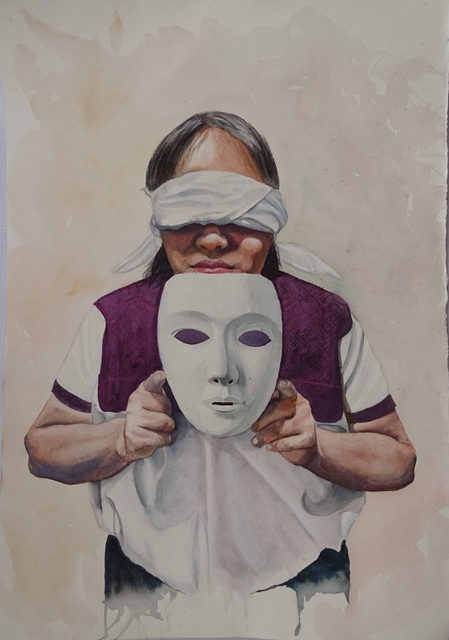

In September 2021, the United Nations Human Rights Council called on governments and international forums to provide for greater participation of Indigenous peoples in the design of recovery programs, something which has been echoed in official declarations by the federal government and UNESCO in Mexico. So far, their implementation remains to be seen. For their part, there are many grassroots efforts to build and expand more independent forms of participation, including the investigative journalism and podcasts in Spanish and Indigenous languages produced by Chiapas Paralelo, the vibrant work of Indigenous artists that reflect the resilience of their communities, the struggle for food sovereignty by small farmers and rural communities organized in Via Campesina, and the ongoing efforts of the Zapatista movement to build alternatives to dominant economic and political models in Mexico and beyond.

Neil Harvey is a professor and head of the Department of Government at New Mexico State University (NMSU). He specialises in politics in Mexico and Latin America, particularly the role of social movements in the struggle for democracy and new forms of political representation. Neil has written extensively on rural politics and indigenous people’s movements. The research for this article was carried out upon a recent trip to Chiapas, Mexico. Research assistance provided by Camira Haughton, NMSU.