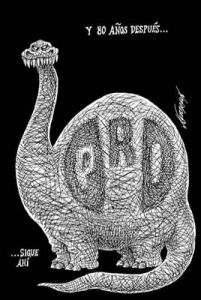

“And 80 years later…still here”With the clear victory of its candidate Enrique Peña Nieto in last week’s presidential contest, Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) has completed a triumphant return to power after 12 years in opposition.

“And 80 years later…still here”With the clear victory of its candidate Enrique Peña Nieto in last week’s presidential contest, Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) has completed a triumphant return to power after 12 years in opposition.

The PRI lost control of the presidency in 2000, after more than 70 years when the destiny of the country and that of the sprawling nationalist movement that emerged from the Mexican revolution seemed forever intertwined.

Paradoxically, it was reformers inside the PRI itself – Presidents Zedillo and Salinas – who set in motion the possibility for the PRI to be voted out of power. By the mid-1980s, these technocratic leaders bowed to pressure from the United States to make Mexico more ‘democratic’ by bringing in more transparency and establishing more independent institutions, from the judiciary to the electoral authorities.

As a result, by the end of the last century the groundswell of dissatisfaction with the authoritarian ways of the ruling party was enough to bring Vicente Fox, the first opposition president, into office.

Further liberalisation under PAN

The party he led, the Party of National Action (PAN), in fact merely continued what the last 20th century presidents from the PRI had begun. President Fox sought to liberalise the economy still further, and to align Mexico even more closely with its NAFTA partners the United States and Canada. (Fox had been an executive in the Mexican subsidiary of Coca-Cola before entering politics).

Over the past six years, his PAN successor as president, Felipe Calderón, has continued with similar policies. The links with the United States have been more important in foreign affairs than any ties with Latin America, as Mexico and Colombia became the super-powers closest allies in the region. In domestic politics, Calderón’s overwhelming priority was to confront the drugs cartels that had grown immensely powerful over the previous decade. To do this, he brought in 50,000 troops to take on the cartels’ gunmen: in the ensuing conflict, an even greater number of Mexicans (the vast majority of them not involved in the illicit drugs trade, despite Calderón’s claims) has been killed.

The increased sense of security brought about by this violence, plus the inability to create jobs and provide solid economic growth, were what gave the PRI the chance to regain power in the 1 July 2012 elections.

A ‘reformed’ PRI

Their candidate, the photogenic Enrique Peña Nieto (who will be 46 this July), was carefully chosen to show that he represented a new, ‘reformed’ PRI that could show it had learned its lesson from more than a decade in opposition. Although his election has been challenged because of many alleged irregularities, Peña Nieto has promised to respect democratic freedoms, and declared his aim to ‘recuperate the road of peace, security, economic growth and effective action against poverty.’

Putting these promises into practice is going to be a huge challenge for the incoming president. He has already said he will take the fight against the drugs cartels out of the hands of the army, and create a new federal police force.

But it was the endemic corruption at all levels of the existing police forces that led his predecessor to bring in the armed forces in the first place, so how is President Peña Nieto going to change this? The fact that he is intending to bring in Oscar Naranjo, until recently head of Colombia’s police, to advise him in this has already ruffled nationalist feathers, not least within his own party.

The PRI, or some parts of it at least, are also unlikely to accept any further liberalisation of the economy. In opposition, the PRI blocked attempts by the two PAN governments to break up the state-run PEMEX’s monopoly of the oil sector, as well as other reforms in the energy, insurance and pension sectors.

Optimistic observers in Mexico stress that the country has changed in the years since the PRI was last in power. They point to the emergence of key independent institutions ranging from the Central Bank to the Supreme Court. They also point out that the PRI is likely to be in a minority in the lower house of Congress, and that the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) controls Mexico City, the second most powerful political position in the country, while opposition governors head a third of Mexico’s 32 state governorships. All of this, they argue, will prevent Peña Nieto and the PRI from returning to theor old authoritarian ways.

Many more decades of PRI rule?

Mr. Peña Nieto takes office in December of this year. It will soon become obvious whether he does represent a ‘reformed’ version of the PRI, or whether he will allow the ‘dinosaurs’ of the party, who for years dressed up their corrupt manipulation of power in the jaded rhetoric revolution, to regain the upper hand. If they succeed, his six years in office could be chiefly aimed at consolidating the PRI in power for decades to come.