It is almost 12 years since the Mexican government ‘declared war on violence’. Since then there have been thousands more homicides and people declared missing. Narcoculture and violence have become normalised in Mexican society. Everyone is affected, but none more so than children, who exhibit more aggressive behaviour and violent play.

How violence impacts children

In May 2015, Christopher, aged just six, was intentionally killed in a marginalised neighbourhood of Chihuahua by five children aged 11 to 15 as they played, pretending to be kidnappers. They tied Christopher’s hands and feet and beat him with stones, branches, and a knife until he died, when they covered him with soil.

This event was a reminder of the harsh and violent reality in which children are growing up, a context where they learn that ending the lives of others has few if any consequences and where they learn to repeat that behaviour.

With the number of homicides increasing over the years and acts of violence among children, it is necessary to ask whether cases like that of Christopher are isolated, or all children are influenced by violence.

Violence is normal in society

In the state of Chihuahua in the north of Mexico, preschool teachers have observed the changes in the children’s behaviour and play. They believe this is due to community exposure to the violence generated by the drug war between the Government and organised criminal groups, with civilians caught in the middle. The street is a common site for murders, kidnappings, and other crimes. Chihuahua has been one of the five states with the most homicides since 2012.

Children often directly witness the violence that occurs in their communities and it is common for them to chat about what they have seen. They learn to accept violence as normal, and exhibit anti-social behaviour that gets in the way of learning at school, for example fighting with peers, arguing with teachers and not following rules. One teacher, Paula, noted:

‘Children have conceptualized violence as normal, from day to day, even at their home family fights are normal. Then when they go to school, they show clear signs of apathy (in their relationships with others)’

Laura, another teacher, commented, ‘Children comment on death or shootings very easily, without showing any feelings about it’.

Teachers find that children who have been exposed to community violence are less motivated in games and withdraw from activities that used to interest them in the classroom or the playground. At the same time, many children become anxious and easily irritable. Sofia noted: ‘Our school has not been directly affected. However, when something happens (violence outside the school) children get anxious”.

The violence also affects their relationships with peers because they cannot self-regulate, leading to disruptive behaviour in the playgrounds and classroom, which becomes an obstacle to learning.

In rural areas where there is no strong police presence, criminals move more freely in the community. Here young children are exposed to violence in a different way: while there are fewer crimes against civilians than in the city, the children see the criminals and their work in their neighbourhoods. As Samantha describes:

Teachers report that they see children playing violent games modelled on the violence they have seen in their community and in the media. The ‘games’ include imitating guns or knives with other objects, and pretending to fight, murder, or be hitmen or narcos.

A problem for teachers

Almost all the teachers we spoke to have implemented strategies with students affected by exposure to violence, devising lesson plans and conversations with parents to raise awareness of why violence is wrong and why children should not be exposed to it.

‘It is important to work the socio-emotional area. However, it is difficult to get children to show respect or empathy towards others because they see violent acts so frequently’

Equally important, teachers want more support from the education authorities to address the effects of violence on children, with a curriculum that incorporates solutions to these problems, psychological support for families and children, and awareness campaigns.

Even in Mexico’s preschools, violence and insecurity pose challenges for teachers. The children’s behaviour presents real difficulties for teachers who feel a responsibility to address the problems. Their attempts to help young children places at risk their own physical and emotional well-being as the problem goes beyond their capacity to address it with the limited resources at their disposal.

The scale of the problem

The scale of violence in Mexico and its infiltration into all areas of life requires solutions far beyond what can be achieved by classroom activities.

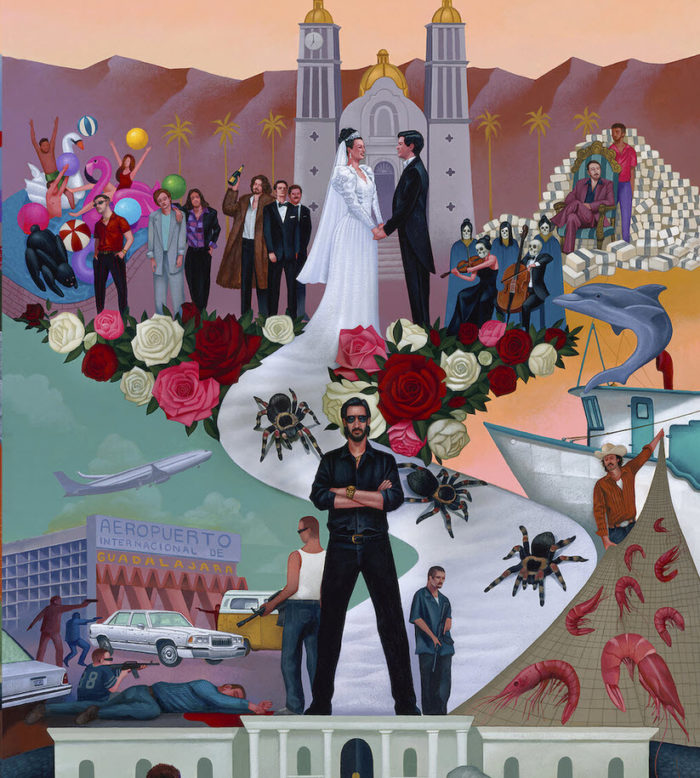

The omnipresence of violence in popular culture adds to its normalisation. For example, the violent behaviour of cartels is romanticised in TV programs, series, movies, and songs (narco corridos) that glorify the lifestyle. Netflix series such as Narcos México tell the stories of the rise and fall of Mexican cartels, portraying the history of figures like Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, inviting viewers to empathise with how, from humble beginnings, he worked hard and became a millionaire and was a responsible father; or Amado Carrillo Fuentes who is depicted searching and protecting his lover.

Most of the teachers we spoke to agreed that children from their schools see or hear about acts of violence from social media, songs, television, and in their household and community. Regardless of teachers’ recommendations, many parents do not consider that consuming violent content from media can have negative consequences on children because they too are consumers of such content.

States including Sinaloa and Baja California have imposed limits on playing narcocorridos, songs that celebrate narcoculture. Elsewhere however, efforts to reduce the broadcast of content perceived to promote violence have largely failed in the face of claims that such measures constitute censorship.

In 2011 some of Mexico’s top broadcasters agreed not to praise narcos, nor print their propaganda. Nonetheless, it is disturbingly normal to see photographs of victims of people killed or bloodily wounded on the front pages of digital or printed news, as well as images of both adults and children using weapons.

In recent years, violence has increased significantly. Since the beginning of AMLO’s presidential term in December 2018, the number of homicides each year has increased by 33 per cent. According to TResearch and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), in the 34 months of AMLO’s government, it has registered 97,254 homicides, of which 37 per cent occurred in 2020. Of those homicides in 2020, seven out of ten involved firearms.

AMLO’s policy of ‘hugs not bullets’ has not worked. Crime has increased and the cartel networks continue to terrorize entire towns, while complaints are made against security forces, including the new National Guard, for human rights violations. The complaints include premeditated murder, torture, and cruel and degrading treatment. Meanwhile, many perpetrators of violence go unpunished due to the inadequate judicial system. The lack of support and cuts to resources mean that the public prosecutors cannot open more cases, meaning that a staggering 94.8 per cent of the reported cases go unpunished.

In August 2021, the Mexican state sued several US gun companies for negligence in the sale of weapons in an attempt to control the availability of weapons in Mexico. According to the lawyers, these companies are the main arms dealers for the drug traffickers, which has resulted in thousands of deaths in the organized crime war in Mexico. One example cited in the case is Colt’s Manufacturing Company which produces three .38 calibre pistols called ‘El Jefe’, ‘El Grito’, and ‘Emiliano Zapata 1911’ obviously targeting Mexican buyers. The lawyers claim that these guns are ‘status symbols coveted by the drug cartels’. The case is ongoing.

Exposure to violence has made children perceive it as something normal, that they hear about on the news, in popular music, or from adults. It affects their ideas, leads them to display aggression in their games and daily behaviour, as it becomes part of their culture While combating violence is a problem beyond the power of teachers and schools on their own, it is important that as adults we do whatever we can to help children to develop and learn in healthy environments.

Main image: UNICEF (taken from 2019 report)

Part of the research for this article was completed under the supervision of Dr Samyia Ambreen, School of Education, University of Leeds.

Ana Karen Reyes is a Mexican teacher and junior researcher. She specializes in children, violence and social studies of childhood.