By Mariana Simões, Agência Pública

Agência Pública is a LAB partner, and provided this article for publication in English by LAB. Translated by Julia May, Wide Avenues . You can read the original version in Portuguese here.

‘Do you think I’m not scared? I am. They know who I am. Now, it’s not just me who’s afraid,’ says the teacher Marlucia Santos de Souza, bending over the desk to get closer to the voice recorder, as if afraid of being overheard. No one else is around. ‘Everyone knows São Bento is controlled by the militias. So we residents have to deal with the fact there is no alternative. But we also have to defend our rights. Making complaints is a way of trying to find a solution,’ she adds. Marlucia is a woman of short stature with a fearless air. Her blue glasses contrast with her shoulder-length, straight black hair and loose, neutral clothes.

On March 7 this year, Federal Police (PF) agents asked this courageous woman to accompany them on an investigation in an environmental protection area. Besides being a state school teacher, Marlucia is the coordinator of the Heritage and Historical Reference Center of Duque de Caxias, a municipality in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro, and she also serves as executive secretary of the Municipal Council for the Defence of the Environment (Comdema).

The police wanted to investigate an illegal land-grabbing scheme in Guedes, a community also known as Novo São Bento, in Duque de Caxias. Since August 2015, residents have been complaining to the authorities that militias are getting the upper hand in the community, where more than a hundred families live, according to local leaders. Their objective: to profit from the illegal sale of land.

Militias in Brazil, which mainly operate in the metropolitan region of Rio, are gangs made up of current and former police officers who control areas of the city by force under the guise of fighting drug gangs. They profit through protection rackets and selling the right to access services such as electricity, gas, water, internet and landfill. In Guedes, the objective of the continuing occupation by the militia is to profit from the illegal sale of land.

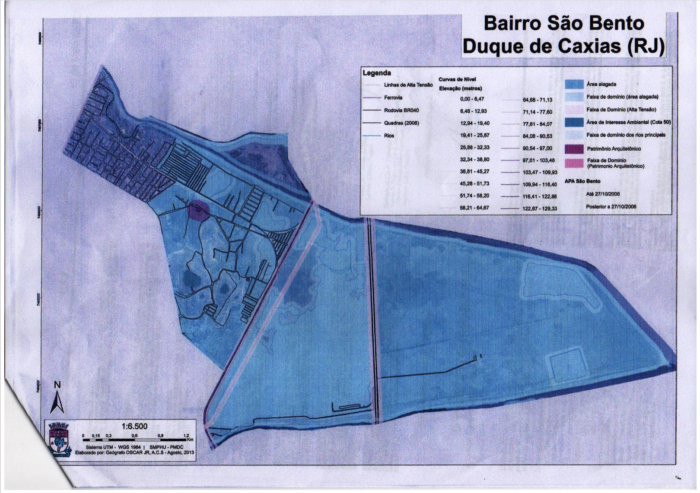

Surrounded by the Iguaçu and Sarapuí rivers, Guedes appears to be sprouting from a green oasis, as the area is surrounded by mangroves. Sales of plots and the construction of new buildings is not permitted in the entire area of São Bento, which is public land. According to the federal government’s National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), the land was acquired by the state in 1931.

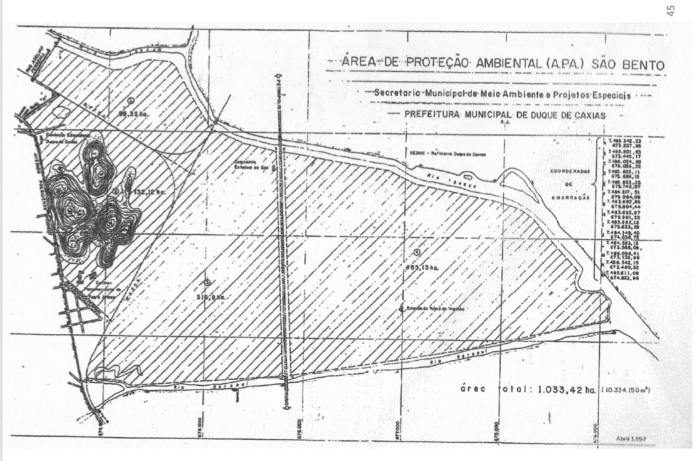

In addition, the community is located within the thousand-acre São Bento Environmental Preservation Area (APA), home to one of the last remnants of the Atlantic Forest, near the urban centre of Duque de Caxias. The APA was established as an ecological space in 1997 by a municipal decree (the Guedes community already existed there), stating that ‘activities that degrade or cause environmental impact’ are not allowed.

Although they are illegal, land subdivision and land sales have persisted for nearly three decades.

Over four months of investigation, Pública gathered documents, interviewed witnesses and talked with the public authorities in charge of investigations. We found that residents live in fear and are subjected to the comings and goings of the dump trucks used by the militia to appropriate land and allocate more illegal plots. To make matters worse, the local government has built a bridge facilitating the entry of those same trucks.

Although it proved that the accusations were well founded, a police inquiry into the advance of land grabbing in Guedes was shelved by the Public Federal Prosecutor (MPF). An order issued by the MPF stated that over the past four years the PF (police) had failed to ‘define the location of the irregular allotment and the people involved with the illegality’. However, Pública obtained a copy of the PF’s investigation, which contradicts this statement.

‘This is an area undergoing ground works, where there are already brick constructions and signs of land occupation advancing in the direction of the banks of the river, in the local area and in the opposite direction as well,’ stated the PF report.

‘It was possible to ascertain,’ the report continued, ‘that the area is controlled by the militia, who influence the city council and public notary offices in the region so that they are able to legalize the invaded areas. Other areas of the reserve are being occupied.’

The findings were so alarming that, in April, prosecutor Julio José Araujo Junior of the MPF in a neighbouring municipality, requested the reopening of investigations. ‘This practice [of land grabbing] has reestablished itself, and now we have another enquiry, taking into account the recent data from the investigation that was carried out,’ explains the prosecutor.

The mis-selling of land prone to flooding

Guedes itself was founded by militiamen. Throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, the militias allotted and sold the land to about 80 families who have remained in the area for nearly three decades.

Families living there say they were deceived by the militiamen when they bought their homes. ‘You just believe them. We went to the notary’s office, the primary office, our signatures were validated. For us, everything was legal,’ said a resident of Guedes, who did not want to reveal his identity. Many of them are poor families who came from the Northeast of Brazil with the dream of finding work and building a home of their own in Rio de Janeiro. Today, they live in fear of the militia, which plans to expand the settlement.

In addition to the sale of land being illegal, the plot where the appropriation of native vegetation and the construction of new homes occurred has been deemed a hazardous area. Guedes sits on top of a polder – an area of natural flooding from the surrounding rivers. In addition to being at risk, people who build on these lands increase the risk of flooding in the remaining occupied areas of São Bento and other surrounding areas.

In 2012, the state environmental inspectorate, in partnership with the Ministry of Cities, promised to integrate Guedes residents into the Projeto Iguaçu housing program, relocating them to a safer area. The program envisaged the resettlement of 2,500 families living in areas of high flood risk on the banks of the rivers as well as construction works to contain the floods. However, in June 2017, residents received the news that the project had been canceled.

Prosecutor Julio Araújo affirms that the city council does not seem interested in resettling residents. ‘I tried to reverse this by calling the city council, and it was a very difficult dialogue with them because the city council didn’t want to cooperate. It had other plans for the area. And then, when you cannot provide the means for people to exercise their right [to resettlement], we move into the area of accountability, seeking to make the authorities responsible for what happened. That is what we are doing today,’ said the prosecutor.

While plans for the illegal expansion of Guedes continue, the city government seems to be more interested in advancing another project: an access bridge, the construction of which is being investigated by the MPF.

The issue at hand is the widening of a bridge within the São Bento APA, built by residents to facilitate access to the Guedes community. After improvements were made by City Hall, the bridge can now handle much larger vehicles. The construction work, according to the PF investigation in March 2019, ‘facilitated the access of trucks that carry rubble for the occupation of the said area, which according to our information, was previously accessed only by carts.’

‘The Municipality of Duque de Caxias has been revealing itself as a notorious violator of environmental norms and socio-environmental requirements for properties,’ said the MPF in a recommendation issued last year. The document also points out that Duque de Caxias is facing no less than six investigations regarding the violation of environmental norms involving real estate.

Trapped amongst wolves

The suspension of the resettlement process by the city council gave a clear signal to the militias, according to Marlucia. ‘Then I think it was like a feast for the wolves.’

For Marlucia, the resettlement of residents would have helped to impose public order, sending the message that new building would not be tolerated. But since the removal of the residents did not happen, she said that the way had been cleared for a new advance of construction.

‘The militias no longer have brakes on their expansion projects. They are consolidating. When the PF came here, one of the things they asked was how these guys got a street lamp here if this is INCRA land and an environmental preservation area? Here the militias are the mayors of the area. They put up signs, open streets,’ he says.

The new land grabbing and occupation process has been going on for two years and is still in full swing, Pública was told by residents. It begins with the burning of vegetation to make room for land allotment. The practice itself is already an environmental crime, because it occurs in the middle of an ecological area protected by law.

Then comes the rubble, composed of civil construction waste, on a large scale, followed by the sale of lots for just under US$3,000. ‘They use this debris to occupy and then sell the plots to poor workers,’ continues Marlucia, who points out that the debris also contaminates the soil.

Every day at dawn, residents wake up to the sound of trucks pouring rubble outside their homes. According to residents, the action takes place at dawn so that it goes unnoticed, and the purpose of the rubble is to build the foundation of new homes in the area.

Truck drivers, who arrive daily, do not identify themselves when entering Guedes and, due to security conditions, residents and police cannot tell where the rubble is coming from; but the Federal Police investigation confirms the residents’ version that the flow of vehicles is also controlled by the militia, which charges for every skip of rubble unloaded at the site.

During the day, the population of Guedes is forced to live with rubbish, dust and chaos. ‘Today, the place looks like a war zone to me. It looks like a bomb was dropped there. Very ugly,’ says one resident. ‘We are embarrassed to invite people to see where we live. Because when you arrive, you will soon see rubble, rubbish, old toilets,’ adds another resident.

How the militias grab territory

The situation is an example of how militia-dominated territory is being expanded, according to sociologist José Cláudio Souza Alves, who has been studying the expansion of the armed groups in Rio de Janeiro for 26 years.

Although they are best known for practices such as executions, trafficking and charging ‘security fees’ from residents of the communities they control, Alves argues that the main practice of militias in Rio de Janeiro has long been the sale of land and real estate. ‘It’s not a new thing. But now it’s become an uncontrollable, monstrous thing,’ he says. He claims that Rio’s militias are more powerful than the drug gangs, as they have close ties with the political world.

In the case of Guedes, militia action is still in its infancy, but for José Claudio, the trend is of expansion. ‘To sell houses, you have to have land to build on. So the logic is land-ownership, with the highest possible density of inhabitation, to ultimately make the biggest profits,’ he says.

In Guedes, the militia still sells clandestine services such as the distribution of water, electricity, gas and even TV signal, from forged contracts. According to residents, although the range of services offered is increasing, they still do not feel obliged to use them.

‘For now, they only offer services. Then they will start charging fees and forcing people to use the service,’ says one resident. ‘In future you will have to pay to get inside your house. This future is very close, very close,’ adds another.

One resident says he feels completely abandoned by the government. ‘We feel like we are animals,’ he said. ‘Animals with no one to hear our groaning.’

‘We dream of an afforestation project for São Bento and the recovery of the Iguaçu and Sarapuí rivers. There is the potential for tourism, research and to improve the quality of life for residents. We dream of having residents with water, light and without the intervention of the militia. Only we can see that our legs are shorter than theirs. How are we going to move mountains and stop this happening if people are scared?’

Despite this, Marlucia sees hope in the residents’ insistence on continuing to report the illegalities that have persisted for decades in Guedes. ‘There are many people who make complaints to the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Many people. That is a good thing,’ she says.