This is the latest post in LAB’s London Mining Network blog, a partnership initiative between LAB and LMN. It contains a roundup of Latin America-related content from London Mining Network’s January 2022 newsletter, with additional material supplied by LAB, researched and written by Kinga Harasim.

Argentina: Another attempt to impose mining in Chubut failed.

‘We show that democracy comes from the street’ – Viviana Moreno, No a la Mina Esquel

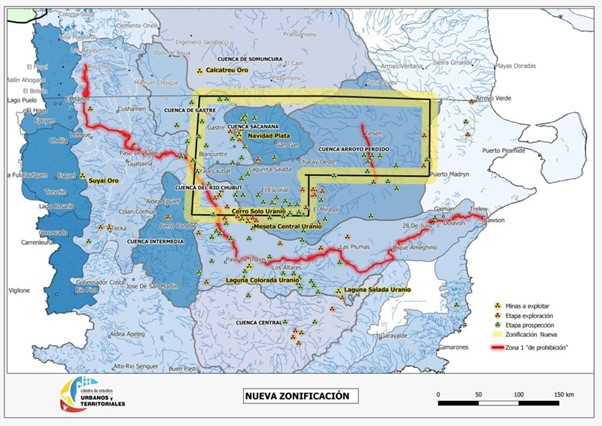

Protests returned to the streets of Chubut, in the province of Patagonia, after the Provincial Legislature approved The Mining Activity Rezoning Law, which would allow activity in Telsen and Gastre, where the multinational corporation Pan American Silver owns the Navidad silver and lead deposit. Despite the fact that communities recently rejected mining in a referendum and that the province has had legislation (Law 5001) prohibiting open-pit mining since 2003, the government unexpectedly called an emergency session on 14 December, at which 14 deputies voted in favour of the project and 11 voted against it.

Shortly after the news broke, protesters gathered outside the Legislature building in Rawson, the provincial capital, to oppose the approval granted to the project. Things heated up when security forces in riot gear confronted the crowds, fired rubber bullets and tear gas and used extreme violence to make arrests, as denounced in social media.

‘Behind the scenes and in a grotesque manner, this demonstrates how mining not only degrades the environment but also democracy… There are marches all over the province; it’s a disgrace,’ said Enrique Viale of Argentina’s Association of Environmental Lawyers. ‘Thousands of rubber bullet rounds to impose mega-mining in Chubut. Just like that, by shooting, using force, tampering with institutions, and destroying democracy.’

‘We know that the only way to get mining approved in Chubut is through repression; there is no other option. Yesterday, there was a lot of outrage over what happened the night before, with hours of constant repression, which I had not seen in 20 years of activism, where at 2 a.m. we could still see policemen on motorcycles, in vans, in civilian clothes, shooting at anyone who passed them on the street,’ said Pablo Lada, an environmental activist.

Following the violent repression, protests intensified over the next few days, spreading to other towns throughout the province. A group of masked people set fire to Government House in Rawson, as well as some other buildings including governor Mariano Arcioni’s notary office. Protesters denounced the presence of police infiltrators who started fires in order to justify criminalization of the protest and repression. They noticed that the police were nowhere to be found when the incidents occurred, whereas the day before when protests were peaceful, they were everywhere.

A prosecutors’ team is looking into whether there was a ‘liberated zone’, where the police deliberately absent themselves because they are a party to the crimes that are carried out. However, Victor Acosta, Chief of Police in Chubut, ruled out this theory, stating that police forces acted ‘in accordance with the governor’s orders to avoid any type of confrontation’.

No means No, Mr. Governor!

The new mining law was proposed by Mariano Arcioni, the governor of Chubut, who previously gained popularity by campaigning against mining in the region. He changed his approach after assuming office, and mining became his primary strategy for development in Chubut.

‘We don’t believe in his lies; in 2017, when he was a candidate for National Deputy, Arcioni filled the province’s media with anti-mining advertisements, and now he wants to stab you in the back,’ the protesters said. ‘No means no, Mr. Governor; do not provoke us any further, and do not yield to pressure from a national government.’

Moreover, some of the deputies who voted in favour of the project were previously involved in corruption scandals. For example, Graciela Cigudosa resigned as Minister of Education following allegations of corruption. Another deputy, Sebastián López, was caught asking a multinational mining company for a 100,000 peso payment in return for lobbying on their behalf .

‘The Arcioni government has shown numerous signs of corruption; some of them are on trial, while others are already imprisoned’ stated one of the activists. ‘They buy their vote, offering them a seat as a deputy, which ensures they will vote in favour of any project presented by the provincial executive.’

Despite the governor’s public declaration that he will not overturn the decision, after six days of massive protests, he called another voting session in which 23 deputies voted to repeal the Law. Furthermore, he announced that he will hold another Popular Consultation to hear the will of the people. People were celebrating on the streets across the province, chanting in front of the legislature, ‘The people united will never be defeated.’

‘We show that democracy is practised on the street, not by the authorities, and that we, the people, have the potential to define our own destiny, even in the face of the extractive dictatorship imposed by powerful economic groups,’ said Viviana Moreno from the organisation No a la mina Esquel.

Brazil: The mine railway which damages communities along its route

Brazil’s Fiol railroad project has been met with strong opposition from communities along its entire length. Despite the government’s promise that new infrastructure will spur development and job creation in the region, activists claim that it has so far resulted in conflicts, loss of livelihoods and environmental damage.

The initiative involves the construction of a ‘logistics corridor’, principally a railway line, connecting Brazil from east to west. Initially, it was part of the Federal Government’s plan to expand the rail network, in order to rebalance transportation and reduce transport costs for Brazilian products. Valec, an engineering firm, was commissioned to build the structure.

However, in April, the Brazilian mining company Bahia Mineração (Bamin), a subsidiary of the Kazakhstani company Eurasian Group Resources (ERG), won a government tender to operate a segment of the East-West Integration Railway (Fiol) for 35 years.

This will make it easier for Bamin to ship iron destined for the Chinese steel market from its Piedra de Ferro mine in Caetité to a new port at Porto Sul in Ilhéus. The Fiol is now 80 per cent complete, so Bamin must complete the missing section. Porto Sul is still under construction and is scheduled to open in 2026, while the Pedra de Ferro operation will last about 30 years.

‘How can a licence for the port be issued before the railroad is there? And how can the mine be approved without knowing how it will ship [the ore]? Everything was done in a hurry,’ said Maria do Socorro Mendonça, an activist.

Whose development?

‘What is at stake is the type of development wanted for this region,’ says Rui Rocha, professor at Santa Cruz State University (UESC). ‘Is it still our role in the twenty-first century to generate wealth for other countries? Why not improve the roads in the area, train people in sustainable agriculture, fishing, tourism, or even low impact industries like information technology – which we already have?’

Communities along the new railway line believe they have been largely excluded from the development process. They were not only not consulted about any resulting changes to their territories, but they were also left in the dark about what was going on and how it might affect their lives or the environment at each stage of the process.

Communities being split in half, forced displacements, property damage, contamination, and overexploitation of water resources are just a few of the project’s side effects. Many families have lost their source of income.

The fishers of Vila Juerana, for example, whose main fishing area is precisely where Porto Sul is being built, have already demanded compensation, as about 4,700 people from the two fishing villages will lose their livelihoods. Bamin responded by offering around 12,800 reais (US$2,228) per village and 7,000 reais (US$1,218) per association. After the Z-34 village divided the money equally among the members, each would receive merely 4.74 reais (US$0.83) as compensation.

In addition, over 1,000 jobs would be lost from the cocoa farms due to their land being expropriated. Rui Rocha says that ‘the numbers just don’t add up,’ when compared to the project’s goal of creating 1,500 jobs.

‘Cocoa has been cultivated for centuries, and artisanal fishing has been practiced for thousands of years. The region has the potential to develop community-based tourism, which could last for several generations. But priority is given to a short-term project,’ said Maria do Socorro Mendonça, a social activist.

On the other end of the railway, the municipality of Licnio de Almeida accuses Bamin of emitting toxic dust during ore transportation. They claim it can be seen coating furniture inside the homes and in the air, and that contaminated water has recently caused an outbreak of the virus. ‘The dust is really bothering me, I feel sick. We eat and drink dust here’- says Durvalina de Jesus, a pensioner. Furthermore, there is growing concern about the tailings dam that the company intends to build, particularly in light of the failures of the dams at Córrego do Feijão (Brumadinho) in 2019 and Fundão (Mariana) in 2015.

‘This project is implemented with violence,’ says Lucas da Silva, member of a Quilombo community. ‘We are not here to criticize or oppose development. But the fact is that we are here, we’ve got here first, our ancestors have always lived here… We don’t want to change our way of life; we just want to stay here quietly and peacefully as we are. We hope that the government will listen to us, as well as society, because society often sees only development. But development for whom?!’

In other news…

Perú: Following the resolution of a social conflict with the neighbouring community of Chumbivilcas, the Chinese mining company MMG confirmed the continuation of its operations in the Las Bambas mining deposit in the department of Apurimac. On 30 December, representatives from the government, the company, and the communities met in Apurimac and reached agreement to allow mining operations to resume.

Colombia: On 19 December, six municipalities from Nario and Cauca, San Pablo, Belén, Colón Genova, La Cruz, Cartago, and Florencia (Cauca), took part in a popular consultation against mining. The consultation was held in response to the recent presence in the area of agents from the AngloGold Ashanti company, as well as the grant of 102 mining applications and 16 mining titles. More than 30,000 people attended the consultation session and 99.8 per cent of voters rejected mining.

México: Trade unions demonstrated outside the Government Palace to express their dissatisfaction with the failure to reinstate Cananea miners from Section 65 who were sacked for organising a strike against the Grupo México company because of its failure to comply with health and safety regulations in the mine. One of the demands is that Section 65 miners be included in the Plan for Justice for Cananea victims of the disaster that occurred shortly afterwards and as a result of the company ignoring the health and safety risks of their operations.

Main image: Chubut protest. Conclusión Buenos Aires / No a la Mina Esquel