- The city of Manaus made world headlines last April when a first wave of the coronavirus swept through the city. Now that city, and the entire state of Amazonas, is being swept by a second wave of the pandemic, which is shaping up to be far worse than the first.

- Indigenous people are especially vulnerable, with their mortality rate from COVID-19 at least 16% higher than the Brazilian average. Now, São Gabriel da Cachoeira, located 852 kilometers (529 miles) from Manaus, near the Colombia-Venezuela frontier, is being heavily impacted.

- São Gabriel has a large Indigenous population, and while it escaped the worst of the first wave of the pandemic, its meagre health system resources are now being overwhelmed. The state of Amazonas lacks sufficient hospital beds, its ICUs are overrun, and medical facilities lack sufficient oxygen.

- Of extreme concern is a new Brazilian coronavirus variant called P.1, which recently appeared in Amazonas state. While more research is needed, one possibility is that P.I. is bypassing the human immune response triggered by the initial coronavirus lineage that ravaged Manaus last year. This means people could be reinfected.

This article was first published by Mongabay on 20 January. You can read the original here.

“Health professionals are physically and psychologically exhausted, and patients from Manaus and the interior of Amazonas state are queuing for beds. In a word, we are going through a crisis of unprecedented dimensions. Perhaps we are witnessing one of the most painful situations in the history of this pandemic.”

These dire words were reported by phone on 14 January to Mongabay by researcher Jesem Orellana, from the Amazonia branch of the Brazilian Health Ministry’s Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), one of Latin America’s leading health institutions.

Bluntly put, the nation’s health care system is collapsing in Manaus, as it, and the rest of Amazonas state, are swept by a second horrific wave of the pandemic— maybe exacerbated by a new COVID-19 variant recently detected in the South American nation.

Manaus made headlines round the world in April 2020 when its capacity to deal with high numbers of COVID-19 dead was stretched to the breaking point. Burials were carried out night and day then, as coffins were piled in collective graves. The crisis was finally brought under control in August.

But, starting in late December, the coronavirus came roaring back and escalated tragically, with some health officials believing the Brazilian Amazon’s second wave will prove to be even more deadly.

Indigenous especially at risk

One under-reported aspect of the healthcare breakdown in Manaus is its impact on Indigenous peoples hundreds of miles distant, up and down the Amazon’s many rivers. São Gabriel da Cachoeira is one such place, located 852 kilometers (529 miles) to the west of Manaus, not far from the Colombia-Venezuela frontier. It has a bigger Indigenous population than any other municipality in Brazil, with 92% of the area’s land designated Indigenous territory and 77% of its 46,000 inhabitants belonging to one of the 23 Indigenous peoples who have inhabited the region for thousands of years.

Since Brazil’s colonization in the 16th century, epidemics, brought in by outsiders, have wrought havoc on Indigenous peoples lacking resistance to European diseases and these cultural catastrophes still figure heavily into the collective memory handed down from generation to generation. Indigenous peoples remain particularly vulnerable to these alien diseases, with their mortality rate from COVID-19 at least 16% higher than the Brazilian average.

Aware of the danger the coronavirus pandemic represents for them, São Gabriel’s Indigenous population took early action to try and avoid the worst. On 18 March 2020, organizations there partnered to create the Coping with COVID-19 Committee. Among its members were FOIRN, the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Rio Negro; FUNAI, the government’s indigenous agency; ISA, the Socio-Environmental Institute, an NGO; the municipal health department; and the Brazilian army.

The committee was proactive, combatting COVID-19 before it reached the town. São Gabriel’s populace speaks four official languages (Portuguese, Nheengatu, Tukano and Baniwa) so multilingual booklets outlining preventative measures were produced and distributed, and information broadcast by radio, with the support of young communicators from the Wayuri Indigenous Communication Network and ISA.

These measures prevented the worst earlier in 2020, even as Manaus took the brunt of COVID’s first wave, but by January 2021 it was clear that the epidemic was spreading rapidly.

On 16 January, Floriza da Cruz Pinto, president of the Yanomami Kumirayoma Womens’ Association, told Mongabay: “The situation is getting worse very quickly for us Indigenous along the lower, middle and upper reaches of the Negro River. And it has reached my community, the Yanomami of Maturacá.”

She went on to describe the disease’s rocketing spread: “The situation is very serious in São Gabriel because the hospital there hasn’t enough beds for us, the Indigenous, and the people of São Gabriel.”

That hospital is also ill-equipped to deal with very sick patients. “São Gabriel does not have a single Intensive Care Unit (ICU), and when patients get very seriously ill, they have to be taken to Manaus,” Carla Dias, an anthropologist with ISA, told Mongabay.

But now, desperately ill patients are arriving in Manaus, not just from São Gabriel, but from all over Amazonas, it being the only city in the state to have hospitals equipped with ICUs. The scope of the crisis is stunning: Amazonas covers 1,571,000 square kilometers (606,566 square miles) and is more than three times the size of California. It also has a population of 4.2 million, and the Manaus hospitals are not coping as they try to deal with the runaway pandemic.

Lack of oxygen

According to Union of Amazonas State Health Workers President Graciete Mousinho, “The situation is completely chaotic. We have patients needing oxygen waiting in the corridors and the wards. But we have no more oxygen, no more beds, no more room in the ICU. Patients will have to be transferred to other states. The worst thing is that we see patients trying to breathe and not managing to.”

On 16 January, the Brazilian press reported that the Amazonas state government had relayed instructions to one municipal government in the state’s interior to start digging graves, as it wouldn’t be able to provide oxygen cylinders to any state municipality.

In part, the severity of the crisis is being caused by the unexpected virulence of the pandemic’s second wave. Orellana explains: “Between December 2020 and January 2021, the demand for oxygen [in Manaus hospitals] was three times greater than it was during the mortality peak in the first wave in April and May. This second wave is far more violent than the first.”

According to El País, family members in Manaus are waiting for hours in queues trying to buy oxygen for sick relatives. On 15 January, the Amazonas government issued an SOS, saying it would need to transfer 61 premature babies to another state, as it could no longer provide them with oxygen. The federal government responded, sending in a 48-hour supply of oxygen.

A doctor, who preferred to speak off the record, said: “It’s not a second wave we’re dealing with, but a whole tsunami.”

The armed forces have been brought in to help. According to Reuters, the Air Force evacuated 12 patients from Manaus hospitals to the northeastern city of São Luis over last weekend and brought in eight tanks of liquid oxygen. The Navy is sending 40 respirators.

A new, maybe more dangerous, variant

The new surge stunned Nuno Faria, a virologist at London’s Imperial College. He had co-authored a paper on the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the pandemic coronavirus, in Brazil for Science in September 2020. The research estimated that 75% of the inhabitants of Manaus had already been infected with SARS-CoV-2 as a result of the first wave. This should have been more than enough, researchers believed, for herd immunity to develop.

The pandemic should have been over, but the recent surge shows that this isn’t the case.

“What is happening [now] completely demolishes the idea that Manaus has herd immunity,” Orellana told Mongabay.

Faria is also bewildered. He told Science: “It was hard to reconcile these two things,” the high level of infection in the first wave, and the virulence of the second wave. He and other researchers immediately began to investigate why the herd immunity they predicted has not materialized. On 12 January, they posted their initial conclusions on the website virological.org: Thirteen out of the 31 samples they collected in mid-December in Manaus turned out to be part of a new viral lineage they called P.1.

Although they caution that much more research is required, one possibility is that P.I. bypasses the human immune response triggered by the initial coronavirus lineage that ravaged the city during the first wave. This means people can be reinfected.

The alarming prospect of another full epidemic has created great concern among health experts worldwide, enough for the UK government to decide to ban flights out of Brazil from 15 January. Italy followed suit, and other countries are expected to do the same, including the U.S. under the Biden administration.

If the new lineage also turns out to have greater transmission potential than the earlier one, as now initially hypothesized by experts, the risk for the Amazon’s Indigenous peoples will become even more severe, at least until they are immunized with a vaccine that works with all lineages.

Bolsonaro government stumbles

Brazil’s Indigenous population is already a priority group in the national immunization plan, along with health professionals, the elderly, teachers, security forces and prisoners. But it may be some time before any vaccine reaches them.

That’s because the federal government’s pandemic policy remains contradictory and inadequate. While Brazilian health professionals see vaccination as the only hope, President Jair Bolsonaro told BBC Brasil on 15 December: “I’m not taking the vaccine. Full stop. Will I be putting [my] life at risk? That’s my problem.”

Not surprisingly, some Brazilians have been following the president’s unconcerned lead; the percentage saying they will take the vaccine fell from 91% in August 2020 to 73% in January 2021.

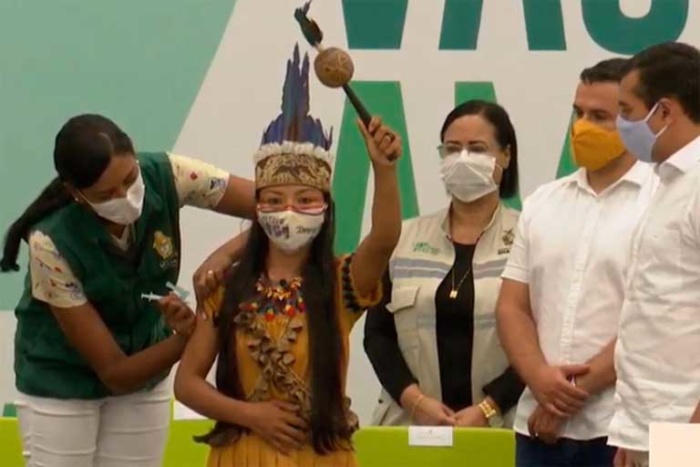

But vaccination has now begun. On 19 January, the first person was vaccinated in Amazonas state — an Indigenous nurse in Manaus. She was given a vaccine manufactured by the Butantan Insitute in São Paulo, using inputs from the Chinese pharmaceutical company, Sinovac. But supplies from China have already run out, with Brazil’s foreign ministry, Itamaraty, admitting that the tense relations between the two countries, partly caused by what were seen as “racist” attacks on China by the Bolsonaro government last year, are largely to blame.

The government still hasn’t developed a viable plan for combatting the pandemic among Indigenous people that is acceptable to Brazil’s Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal, STF). In December, the STF rejected the third version of the administration’s plan, saying it was “too generic.” In his ruling, minister Luís Roberto Barroso decided another version must be drawn up rapidly, stating: “after almost 10 months of pandemic, the federal government has not yet managed to come up with the minimum: a plan with the essential elements. This situation continues to expose the life and health of Indigenous peoples to risk.”

Indigenous groups expect little assistance from the federal government any time soon. “We are waiting here for the vaccine, but who knows when it will arrive,” says Floriza da Cruz Pinto stoically. But, she adds, the people will get through it. “We remain positive. All this will pass with the force of the spirits of nature.”