‘The pandemic will bring tremendous personal health risk to smallholder coffee farmers around the globe, but also a series of financial risks, including market access, global demand, credit access and more.’ (David Browning CEO of Enveritas)

It is estimated that in the first month of COVID-19’s rapid spread, 80 per cent of world coffee shop sales were lost from the effects of mass closures as well as consumers avoiding any outlets remaining open. This is a result of our collective attempt to flatten the ominous curve of transmission, but for countries like Nicaragua, where coffee is responsible for the livelihood of 45,000 families, what will be the consequences of such a plunge in demand?

As a result of the brutal fall in demand in this sector, I have had contracts reduced, and in some cases, cancelled. Because of this, I have had to make huge budget cuts, invest less in the finca, and reduce the workforce.

Jorge Luis Lagos, a speciality coffee producer from Dipilto in Nueva Segovia, Nicaragua, highlighted the challenges being faced by farmers who only produce speciality coffee for ‘small’ or ‘medium’ buyers. ‘Personally, it has affected me a lot because my market is small scale clients who buy speciality coffee for coffee shops and restaurants. As a result of the brutal fall in demand in this sector, I have had contracts reduced, and in some cases, cancelled. Because of this, I have had to make huge budget cuts, invest less in the finca, and reduce the workforce. These cuts will undoubtedly be reflected in next year’s harvest.’

The situation in Nicaragua was already complex. The political crisis of 2018 pushed the country into economic recession – with a decrease of 5.0 per cent GDP in 2019. As civil unrest continued and unemployment levels rose, the country saw a surge in emigration to neighbouring countries. According to a survey carried out by the Italian Institute for International Political Studies, the dream of the majority of young people in the country (around 70 per cent) is to migrate to Costa Rica. The situation has been further compounded by strained international relations and withdrawal of foreign investment.

Nicaragua’s coffee producing regions were hard hit by the political crisis in 2018. Farmers were already on the front line of an agricultural battle against ‘roya’ or ‘leaf rust’, (aka ‘coffee cancer’). Roya is a devastating disease that can destroy years of careful cultivation; over recent years its presence has been exacerbated by changing weather patterns caused by climate change.

On top of these environmental challenges, the political crisis made it even harder for producers to obtain credit for farm investment and large numbers of the workforce migrated to Costa Rica for harvest in the hope of higher wages. Now, with the merciless invasion of COVID-19, will these regions cope with further upheaval?

In order to understand how these impacts are being felt by Nicaragua’s coffee farmers, I spoke to Mirtila Rodriguez, sustainability coordinator for Exportadora Atlantic, one of Nicaragua’s largest coffee trading companies. Mirtila outlined the pressure producers were already facing and how this will be compounded by COVID-19. ‘For the latest season (2019/2020) some farmers abandoned the farms due to the political crisis and the ones who stayed had to face savage price fluctuations. When lockdown started at the end of the harvest, most of the farmers were finishing their tasks so they sent people home. Now it is the time for the post-harvest work and farmers have to prepare themselves for the new crop. They are operating with minimum workforce which is putting them under huge strain.’

Many international organisations are working to support farmers through this critical time. Enveritas, a non-profit organization dedicated to ending smallholder coffee farmer poverty globally, uses innovative technology, including geospatial analysis and on-the-ground observations, to conduct farm assessments. Their technology is adapted for a wide range of producer types and tailored to local conditions. They use this innovation to provide smallholder producers, in countries like Nicaragua, with free sustainability assessment and verification. This helps farmers to improve their practices and gives them access to high-value markets for sustainable coffee. David Browning, the CEO of Enveritas commented that, compared to other coffee-producing countries, Nicaragua has not enforced a strict lockdown. ‘Different countries have taken different approaches. Peru has enacted strict mobility policies whereas Nicaragua has not. The degree to which countries balance social distancing with economic activity will have differing impacts on the spread of the infection and the economic damage inflicted.’

In addition to more lenient mobility policies, there have been reports of miscommunication between the Nicaraguan authorities and the general public. Accurate figures are not being published and patients showing symptoms are being given alternative diagnoses such as ‘atypical pneumonia’, as some doctors and public figures are choosing to call it.

As a result, many coffee farmers are not fully aware of the gravity of the situation which could result in the pandemic having more severe consequences. Rommel Martinez, a senior agronomist who works with smallholder producers in Nicaragua, shared his experience of this miscommunication. ‘Until now, farmers have not taken the situation as something real or dangerous because there is a lot of misinformation from official media and health authorities. There are many cases in the country, but they report less than 10 per cent of these. Therefore, many farmers are not taking it seriously enough. As for government help, there is no support or plan of action from the government directed at the agricultural sector in general let alone the coffee farmer’.

It is important to note that in less economically developed countries it can be much harder to implement social mobility. Where food systems are less developed and social security systems more limited, a total lockdown can have much more negative implications. Rural areas such as Nicaragua’s coffee producing regions would be particularly vulnerable to such impositions.

David Browning was concerned about the plans being implemented in rural Central America.‘The strategies that were employed in Europe may be less effective in a country such as Nicaragua. Smallholder farmers are less able to “shelter in place” if they have limited financial reserves. Food systems are less automated than in Europe, meaning that it may be more difficult to ensure grocery supply chains continue to function while also complying with social distancing. Rural communities are unlikely to have the ICU beds to manage all those needing care.’

Nicaragua was already facing economic recession and because international loans are harder to access, the government is under higher pressure to keep the economy moving. The more the economy shrinks, the more limited credit opportunities will be for farmers. If farmers cannot invest in their land this year, then next year’s crop will be jeopardized. Browning pointed out that ‘coffee farms needing credit for farm investment and working capital will be placed under even greater strain.’

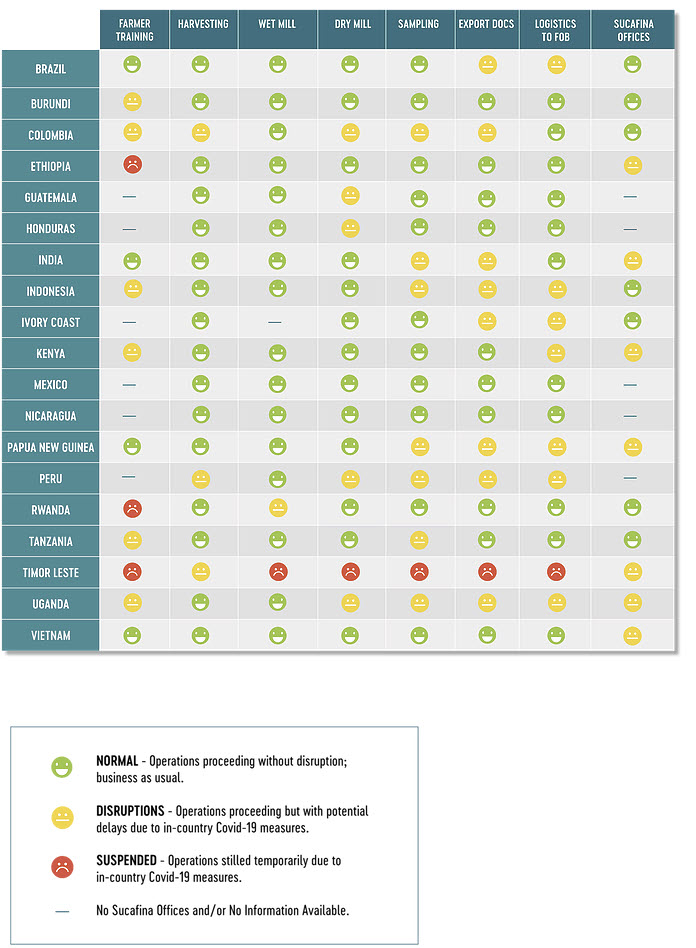

While the helpful and newly established open source COVID-19 information platform, set up by coffee trader Sucafina, shows that the harvest is in and milled and ready for export, market demand for the product is far from certain. While Americans and Europeans in lockdown are drinking more coffee in their homes, it is unlikely that this will compensate for the collapse in demand from coffee bars, cafes, and the wider entertainment sector. What is more, restrictions on international travel will mean fewer origin trips by buyers, reducing important market-access opportunities.

Taking into account the political and economic instability that Nicaragua faced prior to the pandemic and the financial and social impacts that it will inevitably bring, Rommel is concerned for the future of the farmers he works with and the threat of more suffering in a nation that has endured so much. ‘The effects could be catastrophic because we were already in an economic recession as a result of the political crisis and now a global pandemic is going to severely shake the economic stability of an already vulnerable sector which could bring unfortunate consequences such as malnutrition, migration, social movements and severe debts.’

There are two important ways of ensuring the resilience of smallholder producers. Firstly, using technology to drive sustainability. Secondly, the importance of consumers continuing to pay premiums for high quality, sustainably sourced coffee, such as those certified by Rainforest Alliance or Fairtrade. 95 per cent of coffee farmers in Nicaragua are micro- and small-scale producers; while they face such extreme financial pressure, many of these farmers will be unable to meet the sustainability requirements that would give them access to higher market value.

‘With so many challenges being faced both at origin and in consumer countries, it’s understandable that sustainability issues are far less on people’s minds right now; but child labour or deforestation will not go away because of COVID-19. In some cases, these issues may be exacerbated. Consumers’ long-term willingness to pay premiums for coffee brands proactively addressing these issues will not change.

‘Enveritas provides a sustainability approach which uses technology to reduce cost, which allows us to offer a system that is free for farmers which provides some measure of financial relief in these times.’ Furthermore, Enveritas has recognised the power-for-good that their geospatial technology can have as authorities across the regions work in to propel the implementation of COVID-19 testing. ‘We have offered our technology platform to health departments in various countries to support them as they develop randomized testing strategies for COVID-19.’

Coffee producers are one group in a web of communities across the world affected by the devastating effects of this pandemic. A study by Professor Andy Sumner of Kings College, University of London, warned that a recession caused by COVID-19 could push an extra half a billion people into poverty – 8 per cent of the world’s population – unless urgent action is taken. As the last harvest is shipped to Europe and with the lockdown easing only gradually, there is a question mark over the future resilience and viability of Nicaraguan coffee farmers whose situation was already so precarious.

Elizabeth Sanders is a student of Spanish, Portuguese, and Latin American Studies at the University of Edinburgh. Passionate about issues of social justice, in particular, matters of gender equality, she participates in the university’s Girl Up UN initiative and is a member of Model United Nations. She has been interested in social and environmental sustainability since working as an intern in the coffee sector in Nicaragua and Costa Rica.