On 10 December, Alberto Fernández and his deputy Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (no relation) assumed the Argentine presidency marking an end to the right wing administration of Mauricio Macri.

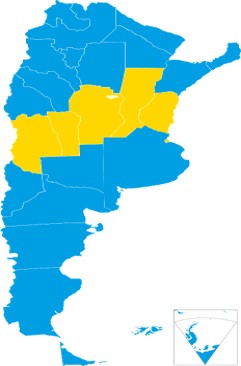

The General Election had been held on 27 October with 33,858,733 Argentines heading to the polls, representing a turnout of just under 82%. The victorious Fernández, at the helm of a broad-church Peronist coalition named Frente de Todos, received a total of 12,945,990 votes (48.24%) as against the 10,811,345 votes (40.28%) achieved by Macri and his Juntos Por El Cambio coalition. Impressively, Fernández was victorious in 18 out of Argentina’s 24 provinces.

The desperate state of the Argentine economy was a crucial factor in Fernández’s victory. It must be remembered that in the 2017 mid-term and senatorial elections the Peronist parties, albeit not united, were resoundingly thumped by incumbent Cambiemos who won 41.75% and 41.01% respectively.

However, to attribute Fernández’s triumph entirely to macro-economic circumstances paints a misleading picture. Other factors, notably the return of Cristina Kirchner, the figure of Fernández himself and the legacy of Perón also played crucial roles.

It’s the economy, stupid

The election was held amidst yet another Argentine economic crisis. In 2018 the economy contracted by 2.8% with no signs of a real recovery on the horizon and shrunk a further 5.2% during the first 6 months of 2019. Moreover, the value of the peso has plummeted over the last 5 years. When the multi-millionaire businessman and economically reformist Macri assumed power in December 2014, the peso was being exchanged at 14 to the US dollar, it now stands at around the 60 mark. Since Macri left office, it has stabilized, declining only slightly from 59.10 to 60.10.

The steady depreciation of the currency and an inadequate government response saw a sell-off of central bank reserves. As investors lost confidence in the peso, inflation spiraled.

Inflation rose from 38.5% in 2014 to 53% in 2019. The crisis reached its height in July 2019 when Argentina signed a loan agreement with the IMF for a total of $57bn making this the largest bailout in history. This loan increased Argentina’s ever-growing external debt to US$284,000,000,000 equating to around US$6,310 per capita. The political costs of external debt are well known as it gives strong leverage to debt holders such as the IMF, hedge funds and the US government.

The IMF bailout fueled anti-government sentiment across the country and brought back painful memories of the 2001-02 economic crisis where IMF-imposed austerity was held broadly responsible for an astronomical rise in poverty and human suffering: in early 2003 unemployment reached 25%, the proportion of the population living in poverty to 60% with around 28% living in extreme poverty.

Obviously there are social and cultural consequences from any such economic collapse. Poverty and extreme poverty have risen once more in Argentina and now stand at 35.4% and 7.7% respectively. Macri, it should be remembered, had promised to bring poverty down to zero.

During his 4 years in office Macri was indecisive and on the whole incompetent. Rather than administering shock therapy he claimed he would reform and modernize the Argentine economy. He relied on a painfully slow form of gradualism, hoping to attract foreign investment while preserving political popularity. Unfortunately, neither happened. Even after his resounding success in the mid-terms indicated considerable support, he failed to capitalize on it.

Macri was obliged to institute austerity measures to curtail an ever-mounting state deficit and to rein in the public spending fuelling that rise. This increased support for the Peronist opposition from the lower-middle and working classes. However, the killer blow to the president’s popularity was a rise in US interest rates and a strengthening dollar.

Investor confidence in the government’s reformist agenda plummeted, causing the already weakened peso to tumble even further. As it entered free-fall the central bank attempted to stem the collapse by using foreign reserves – in the process emptying the coffers. Argentina is now left with a mere $10bn of foreign reserves, a figure similar to that of Venezuela, whilst neighbouring Brazil has $300bn.This collapse of the peso in a country where de facto dollarization pegs the prices of so many basic utilities to the US currency had a significant impact on middle-class consumers, further shrinking the president’s support base.

To blame all of Argentina’s economic woes on Macri is somewhat unfair as many of Argentina’s issues are structural. Since independence in 1816 Argentina has defaulted on its debts 9 times and its economy has contracted in 22 years out of the last 58, second only to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

However, in addition to his economic mismanagement, Macri’s lack of charisma and blunders on progressive issues such as abortion and higher education have all contributed to his downfall. The position he inherited was never likely to be a comfortable one, but his timidity and vacillation doomed him and paved the way for the return of a woman who, for all the controversies that engulfed her own presidency, had shown herself to be both popular and decisive.

Cristina redeemed

The return, in effect the redemption, of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner is key to understanding Alberto Fernández’s victory. Cristina, the previous president, is as loved as she is hated. Many Peronists refuse to accept Cristina as one of their own and instead refer to her (and by extension to her late husband Néstor and the current president Alberto) as a separate movement: Kirchnerism. Yet, separate or united, the two factions are mutually dependent. On her own, Cristina would be unable to win elections, but without her the Peronist camp would remain divided and incapable of victory.

Alberto Fernández, a capable political operator, assumed his position as head of the so-called Frente De Todos. Fernández, like many others, had previously served in the Kirchner governments as Chief of the Cabinet before resigning in 2008 over the issue of agricultural tariffs, and later stating that nothing positive had come from Cristina’s government.

The centrist and pragmatic Fernández was able to reassure many that while Cristina would play a central role in his government, she would not dominate government policy. Kirchnerists were to return to the fold and have since occupied key cabinet positions, with De Pedro as Minister of the Interior, Zanini as Attorney General and Guzman as Minister of the Treasury. However, their advancement paved the way for the return of a number of avowed Peronists who had distanced themselves from the Kirchnerist camp. Sergio Massa, for example, the ex-mayor of Tigre and successor to Fernández as Head of the Cabinet had previously stated publicly on radio that he would ‘never again unite with Kirchnerism’, yet he joined forces with Fernández in June to complete the Peronist coalition.

Mismanagement and corruption

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner became President of Argentina in December 2007 succeeding her husband Néstor and winning 45.28% of the vote which would increase to 54.11% in the 2011 elections.

Positive elements aside, which will be discussed later, the Kirchner administrations were marred by corruption, embezzlement and economic mismanagement. Under Cristina the economic climate became considerably more adverse, with Argentina taking on a more isolationist and fiscally lax economic stance.

Tariffs were placed on export commodities like grain, currency controls were introduced, and the government began to renationalize pension funds and industries such as Aerolíneas Argentinas and the former Ferrocarriles Argentinos. The most problematic example was oil monopoly Repsol-YPF (Yacimientos Petroliferos Fiscales). Public spending increased dramatically as new social welfare schemes like the Universal Child Allowance were brought in.

It can of course be argued that investment and state welfare are the key to stimulating economic growth. Yet under Cristina this ranged from populist measures such as gas and electricity subsidies, to the borderline bizarre with state subsidies for broadcasting premier league football – the Fútbol Para Todos scheme – and for a veterinary hospital in Quilmes.

It was hardly surprising, therefore, that Argentina introduced an AR$ 1 bn cut to public spending in 2011 and adopted an austerity budget in 2012. This, however, was insufficient to stave off another debt default in 2014 during a further recession.

Cristina during this time became increasingly autocratic. She forced the Central Bank to fund international debt and railroaded through the controversial Audiovisual Media Law which provoked a showdown with the Clarín media group. She was accused of obstructing investigations into the AMIA bombings[i].

When Cristina stepped down in 2015 – in obedience to the 2-term limit imposed by Argentine electoral law – public opinion was already turning against her and voters declined to back her appointed successor, Daniel Scioli, fearing that if he were elected, she would be pulling the strings.

Following the 2015 electoral defeat, Cristina and the Kirchnerist movement faced further challenges, as the Macri administration initiated legal proceedings, mostly for corruption, against herself and her former allies. One by one, former ministers like Timerman and De Vido were tried and Cristina herself was indicted. It seemed only a matter of time before she either went to prison or was relegated to political obscurity.

Populism and support

So how are we to understand this relatively rapid turn-around in their fortunes, leading to a new electoral victory in 2019? There are two key factors which explain Cristina’s popularity in Argentina and her enduring status as the keystone of the Peronist coalition: her economic policies, following on from those of her husband; and her identification as the heir to the legacy of Peronist doctrine and ideals.

Nestor Kirchner had entered the Casa Rosada in 2003 with the country in acute crisis and the policies of the previous administrations totally discredited. The first 4 years of his administration saw a concentrated effort to rebuild the economy. With the work of ministers like Lavagna, Prat Garay and Redrado, Argentina successfully capitalized on the international boom in commodity markets fueled by rocketing demand, especially from China, and soon Argentina’s economy was growing at 9% per year. At the same time, Nestor Kirchner successfully gambled by raising minimum wages and investing in infrastructure. He also managed to negotiate the largest debt haircut in global history slashing the country’s overseas debt from US$193bn to US$125bn and reducing the debt to the IMF to a single repayment of US$9.8bn due in 2005.

Social mobility grew under the Kirchners and poverty levels decreased thanks to social policies including an increase in child benefits, healthcare expansion and the introduction of the Progresar educational policy which provided low income families with a notebook computer and funding to access the internet.

This period of economic growth and social mobility consolidated a powerful base of support for Cristina and Nestor.

The three pillars of Peronism

But that support base was built on the abiding ideological legacy of Peronism, a factor fundamental to Argentine politics for almost 70 years.

This legacy enshrined the three pillars of social justice, economic independence and political sovereignty enunciated by Juan Domingo Perón from 1944 onwards.

The belief that Perón cared for and bettered the lot of the working class retains iconic, almost mythical stature in Argentine political memory. Behind this shield, Peronism was been able to traverse the political spectrum over the decades, and adapt its positions on social and economic issues.

This pedigree enabled the Kirchners and Fernández to take the lead on progressive social and legal issues: legalizing gay marriage, pro-abortion, opposing amnesty laws and prosecuting dictatorship-era crimes. These social positions generated a reference point for young people and the disadvantaged.

It was not only social and economic policies that drew on the Peronist legacy, but also symbolic ones. In many ways Cristina tried to present herself as the Evita of the 21st century, a powerful and glamourous woman who cared for the working classes, just as Evita, the beloved wife of Juan Perón, championed labour rights and women’s suffrage.

Equally, the Kirchners drew heavily on the Peronist doctrines of economic independence and political sovereignty. Their fight against international hedge funds struck a chord with many who view their once prosperous country as a carcass being picked at without respite by a consortium of vultures. The strategy, however, has not been entirely successful. In 2012 Argentina was humiliated when hedge-fund NML Capital – one of the creditors which refused to sign up a debt haircut – hoovered up Argentine debt and succeeded in getting the Argentine Navy ship La Libertad impounded. The actions of the vulture funds and the conditions on new loans imposed by international financial institutions still severely limit Argentina’s freedom of action.

As to the

allegations of corruption and mismanagement laid against Cristina Kirchner, many

are happy to blame the large agro-businesses intent on maintaining a monopoly stranglehold

over the economy, and cite the

resistance of these in 2008 to proposed increases in tax on agricultural

exports. In this the Kirchers echo the rhetoric of the original Peronists: that

it is essential to break the monopoly power of the traditional agricultural

elites, who otherwise will remove Cristina (and Alberto) as they did Juan

Domingo.

[i] A terrorist attack on the Argentine Mutual Israeli Association in 1994 which killed 85 people and injured hundreds. Iran and Hezbollah militia were suspected, and the Kirchners were accused of covering this up.