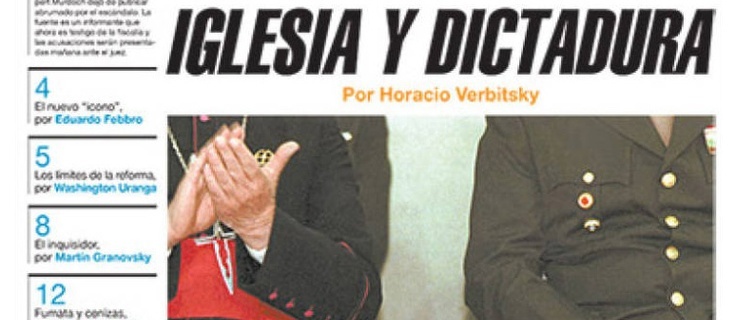

In his first press conference, the spokesman for Pope Francis dismissed charges that Jorge Mario Bergoglio had handed over two Jesuits to ESMA (Naval Officers School of Mechanics), a notorious torture centre during the ‘dirty war’, by describing Pagina 12, the newspaper that had published the charges, as ‘left-wing’. Horacio Verbitsky, the journalist who had made the allegations, replied in hard-hitting article, published in the same newspaper on 17 March 2013. LAB has translated the most important sections. The two Jesuits who were handed over to ESMA were Orlando Yorio and Francisco Jalics.

Shedding Skin

by Horacio Verbitsky

Father Jalics has retired to a monastery in Germany where the German Provincial of the Jesuits explained that this priest had been reconciled with Bergoglio. Jalics, now 85, made it clear that he felt at peace “with those events which are now for me a closed book.” He added that he had nothing further to say about Bergoglio’s role in those events.

For Catholics, reconciliation is sacramental or sacred. In the words of Carmelo Giaquinta, who is a noted Argentinian theologian, reconciliation is “to forgive wholeheartedly the one who has caused you to suffer”. (See note 1, below). But this indicates only that Jalics has pardoned the wrong done to him. It says more about him than about Bergoglio. Jalics has never denied the facts, laid out in his 1994 book on meditation exercises. “Many right-wing people disapproved of us living in poor, marginalised communities. They saw this as us supporting subversion and they denounced us as terrorists. We knew which way the wind was blowing and who was responsible for these lies. I went to speak to the person in question to tell him he was putting our lives at risk. He promised he would make it clear to the military that we were not terrorists. But we discovered later through documentary evidence that he had not kept his promise. On the contrary, he lodged false evidence against us with the military.”

He added that this person “used his authority to give credence to his accusations” and “told those who detained us that we had acted as terrorists. And I had only just told him that he was playing with our lives. He had to be aware that he was condemning us to death with his declarations.”

In November 1977, when in Rome, Father Orlando Yorio gave a similar account in a letter to Father Moura, general assistant of the Company of Jesus. In this case he named the person concerned as Jorge Mario Bergoglio. Seventeen years before Jalics’ book was published, Father Yorio said Jalics had spoken twice to the Provincial Father of the Order, who had promised to quell rumours which were spreading through the Company and to take the initiative to tell people in the armed forces that we were innocent.” He also mentioned that within the Company of Jesus criticisms were circulating about Jalics and himself. It was said twe were “praying strange prayers, living with women, committing heresies and involved in the guerrilla movement”.

In his book Jalics said that in 1980 he burnt documents with evidence of the offences comitted against them. Until then he had hung onto them with the intention of using them. “Since then I have felt truly free and can say I have been able to forgive him with all my heart.” In 1990 Jalics met Emilio Mignone and his wife, Angelica Sosa, in the Prayer and Faith Institute, 2760 Calle Oro. “Bergoglio was against my returning to live in Argentina when released. Were I to leave the Jesuit order, he asked all the bishops to block any attempt on my part to find a position as a diocesan priest.” This information comes directly from Fathers Orlando Yorio and Francisco Jalics, not from Pagina/12.

So, who is being destructive to the Church? Each volume of my Political History of the Church in Argentina includes this warning: “These pages do not judge the dogma or worship of the Roman Catholic Apostolic Church but try only to analyse its behaviour in Argentina between 1976 and 1983 as a sociological phenomenon of a particular people in a particular place as exemplified by its own Bishops’ Conference. The ‘theological reality of mystery’ (see note 2 below) can be seen in the believers, who have earned my respect.”

In defence of the tradition

Bergoglio’s spokesperson attacked this newspaper for being anti-clerical and leftwing. This shows us the persistence of deepl- rooted attitudes. Today’s Pope made the same accusations 37 years ago about his priests, even though it put them in serious danger. The accusations against Bergoglio were made long long before Pagina/12 existed. They were made by the author Mignone, then Director of the official body, Catholic Action, founder of the Christian Democrat Federal Union and deputy Education Minister in the government of Buenos Aires province. All these appointments required the blessing of bishops. In 1986 Mignone wrote his book about the church and the dictatorship in which he said that the military authority cleaned up “the inner patio of the church with the connivance of the bishops”.

Vicente Zazpe, the vice president of the Episcopal Conference, revealed the fact that just after the coup, the Church agreed with the Military Junta that the army would warn the relevant bishop before detaining any of his priests. Mignone affirmed that “in some cases, those same bishops gave the green light to act against them”. The army took the withdrawal of Yorio’s and Jalics’ licence as priests as “an authorization to proceed against them, a direct criticism of them by Jorge Bergoglio, their provincial superior”. Bergoglio was, for Mignone, one of those “shepherds who abandoned his sheep to the enemy without defending or rescuing them”.

Vicente Zazpe, the vice president of the Episcopal Conference, revealed the fact that just after the coup, the Church agreed with the Military Junta that the army would warn the relevant bishop before detaining any of his priests. Mignone affirmed that “in some cases, those same bishops gave the green light to act against them”. The army took the withdrawal of Yorio’s and Jalics’ licence as priests as “an authorization to proceed against them, a direct criticism of them by Jorge Bergoglio, their provincial superior”. Bergoglio was, for Mignone, one of those “shepherds who abandoned his sheep to the enemy without defending or rescuing them”.

By chance I came across documentary proof two decades later which Mignone did not know about and which confirmed his analysis of the situation. It is true that Bergoglio also helped other persecuted people but there is no contradiction here. Pio Laghi did the same, as well as Adolfo Tortolo and Victorio Bonamin.

Conservative but socially aware

We looked in some detail at this case four years before Kirchner formed a government. The first article, published in April 1999, said that the brand new Archbishop of Buenos Aires was “acclaimed by our informant as either the most generous and intelligent person to have said mass in Argentina or a Machiavellian rascal who betrayed his brothers in order to satisfy his insatiable lust for power. Perhaps, in reality, Bergoglio has both traits which don’t always go together. He is very conservative over dogma and also acutely aware of social injustice. In both these he resembles Pope John Paul II who appointed him to lead the principal diocese of our country.”

I said as much on the Thursday when the white smoke deeply moved the kneeling masses from La Quiaca to Tierra del Fuego. That note contrasted Mignone’s account with that of Alicia Oliveira, a lawyer from CELS (Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales) and a friend of Bergoglio, whose sister worked in Villa Flores together with Mignone’s daughter and the two priests. “He told them they had to leave, but they took no notice. When they were kidnapped, Jorge found out that the army had them. He went to speak to Massera [Admiral Emilio Eduardo Massera, hardliner, believed to have masterminded the ‘dirty war’] and told him that if he didn’t have the two priests released, that he as Provincial would accuse him of being responsible of what had happened. The next day they were freed.”

She also referred to the testimony of a Jesuit priest. “The navy did not interfere with any church person, so long as they were not harming the church. The Company of Jesus did not have a prophetic voice then, unlike the Palotines and the Passionists, because Bergoglio was connected to Massera. This was not only in the cases of Yorio, Jalics and Monica Mignone, whose kidnappings were never denounced by the Company. There were two other priests, Luis Dourron (who later left the priesthood) and Enrique Rastellini, both serving in Bajo Flores. Bergoglio asked them to leave there. When they refused, he told the military they were no longer under his protection. And so, prompted by this, they were seized.”

The priest quoted above, who died six years ago, was Juan Luis Moyano Walker, and he had been a close friend of Bergoglio. In connection with this account, Bergoglio offered me his own version, in which he emerged rather as a hero. Both he and Jalics (who I phoned in Germany where he lives in retirement) asked me to attribute this testimony to a priest each of them knew well. Bergoglio said he had seen Videla twice, and Massera also twice. In the first interview with each of them, each had said they did not know what had happened to the proests and would make enquiries. Bergoglio said that: ” in the second meeting with Massera, he appeared annoyed with this youngster of 37 who dared to press the point.” According to Bergoglio, they had this conversation:

“I’ve already told Tortolo what I know”, said Massera

“Monsenor Tortolo”, corrected Bergoglio.

“Look here, Bergoglio”, Massera began to speak, annoyed at being corrected.

“Now you look here, Massera”, Bergoglio replied in the same manner before repeating that he knew where the priests were and he wated them freed.”

I have recorded only what Bergoglio said, with the attribution he requested. But I have never felt this dialogue rang true as it was with one of the most powerful and cruel members of the government, who would have had no scruples in kidnapping Bergoglio.

Massera was made Honorary Professor in 1977 at the Jesuit University of Salvador. He objected to Marx, Freud and Einstein on the questions of the sacred nature of private property, and the “static and inert nature of matter.” Massera felt the University was “a useful means of starting a counter-offensive [against communism] from the West” as though Marx, Freud and Einstein were not a part of the western tradition. Bergoglio was careful to make himself scarce on the day of Massera’s investiture so that no photo should appear of him with Massera. It is hard to believe that the dictator should have been thus honoured without the Jesuit Provincial Superior having approved of the ceremony. He was in daily contact with a civil association run by the Guardia de Hierro.

Later Massera was invited to a conference by the Jesuit University of Georgetown in Washington. On that occasion, Father Patrick Rice, an Irish priest, left Argentina, having been detained and beaten up there. He interrupted the conference, demanding an explanations for the crimes of the dictatorship. Father Rice claimed that the US Jesuit Provincial would not have invited a participant such as Messera without the approval or the request of its Argentinian counterpart. These facts make it very unlikely that the young Bergoglio took onwith the boss of ESMA, as he wouldsuggest.

A Christian death

In 1995 — the year after Jalics’ book came out– The Flight (El Vuelo) was published. In it the captain of the frigate Adolfo Scilingo, confessed to his part in ejecting 30 living people from naval and municipal airplanes over the sea, first having drugged them. He added that this was approved by the church hierarchy, who considered the flight constituted a Christian way to die. The army chaplains comforted those who flew those missions with the biblical parable of the separation of wheat from chaff.

This inspired me to look again at what had happened years before on Tiger Island, known as ‘El Silencio’. This was where the army had hidden 60 people who had been detained or disappeared so that the InterAmerican Commission of Human Rights should not find them in the ESMA. The island once belonged to the Archbishop of Buenos Aires. Each year seminary students used to go there to celebrate their graduation, and Cardinal Juan Aramburu used to spend his weekends relaxing there.

What happened was that Father Emilio Grasselli had sold the island to an ESMA task force in charge of disappearances. who had used a forged document in the name of one of their prisoners. But I had not seen the conveyancing documents until Bergoglio gave me the exact details in the will of Antonio Arbelaiz, the unmarried administrator of the Curia who emerged as the owner. It is typical of the money laundering that went on: Arbelaiz sold the island to Grasselli who sold it to the ESMA who held it with an illegal document. The mortgage was paid to the Curia which was the beneficiary of Arbelaiz’ will. In one of his legal declarations, Bergoglio claimed to have spoken to me about the detention of Yorio and Jalics but he said he had never heard of the island “El Silencio”. Another example of double standards/dealings – private admission and public denial.

Behind their backs

While I was looking into all this, I came by chance upon a file of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I think this is conclusive evidence with respect to the discussion of Bergoglio’s role in relation to Yorio and Jalics. I found a civil servant who knew where this file was lodged in the archives. The then director, Minister Carlos Dellepiane, had it in a safe to prevent its removal or destruction. The story revealed in this file seems familiar. When Jalics was freed in November 1976, he left for Germany. In 1979 his passport expired and Bergoglio requested that the Chancellor renew it, but without his having to return to Argentina. The Chancellor’s Director of the Catholic Faith, Anselmo Orcoyen, recommended that this request be refused “in view of the petitioner’s record” which was provided by “that same Father Bergoglio, who signed the request, clearly asking that it should be refused.”

While I was looking into all this, I came by chance upon a file of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I think this is conclusive evidence with respect to the discussion of Bergoglio’s role in relation to Yorio and Jalics. I found a civil servant who knew where this file was lodged in the archives. The then director, Minister Carlos Dellepiane, had it in a safe to prevent its removal or destruction. The story revealed in this file seems familiar. When Jalics was freed in November 1976, he left for Germany. In 1979 his passport expired and Bergoglio requested that the Chancellor renew it, but without his having to return to Argentina. The Chancellor’s Director of the Catholic Faith, Anselmo Orcoyen, recommended that this request be refused “in view of the petitioner’s record” which was provided by “that same Father Bergoglio, who signed the request, clearly asking that it should be refused.”

He said that Jalics was not clear about his duty of obedience, had a disruptive attitude in congregations of women religious and had been detained in the ESMA together with Yorio as “suspected guerrilla contacts”. In other words, those same allegations which Yorio and Jalics had made (and were corroborated by many priests and lay people I interviewed.) While he seemed to be helping them, he was also accusing them behind their backs.

What happened in 1979 is not sufficient to support his prosecution for the kidnappings in 1976. The document signed by Orcoyen was not even attached to the file, but this report does indicate a certain type of conduct. To say that the Dictatorship’s Director of the Catholic Religion was involved in a conspiracy against the church is a step too far. For this reason Bergoglio and his spokesperson have kept quiet about these documents and choose instead to discredit those who found, preserved and published them.

Note 1 Carmelo Giaquinta: “Reconciling ourselves with our history”. Organised by the project “Seventy times Seven” and Editorial San Pablo, 36 International Book Fair, Salon Roberto Arlt, 8 May 2010.

Note 2 Conference of Bishops in Argentina, National Plan for Pastoral Care, Buenos Aires 1967 p 14, Luis O Liberti, Monsenor Enrique Angelelli. The evangelising pastor who cares for the whole person, Editorial Guadalupe, B.A. 2005 p 164