Peru’s national contender for the 2021 Academy Awards, ‘Song Without a Name’, is a sensitive retelling of a mother’s desperate search for her child.

Peru’s official contender for the Oscars, Song Without A Name (Canción sin nombre) follows a young indigenous woman as she searches for her child, stolen at birth in a fake health clinic in Lima. Shot in black and white, in 4:3 aspect – reminiscent of old TV monitors and films – you’re transported in place and time back to Peru’s war-ravaged capital in the 1980s. As Andreas Roald, the film’s producer, outlines, this simple form allows the characters’ stories and perspectives to take centre stage.

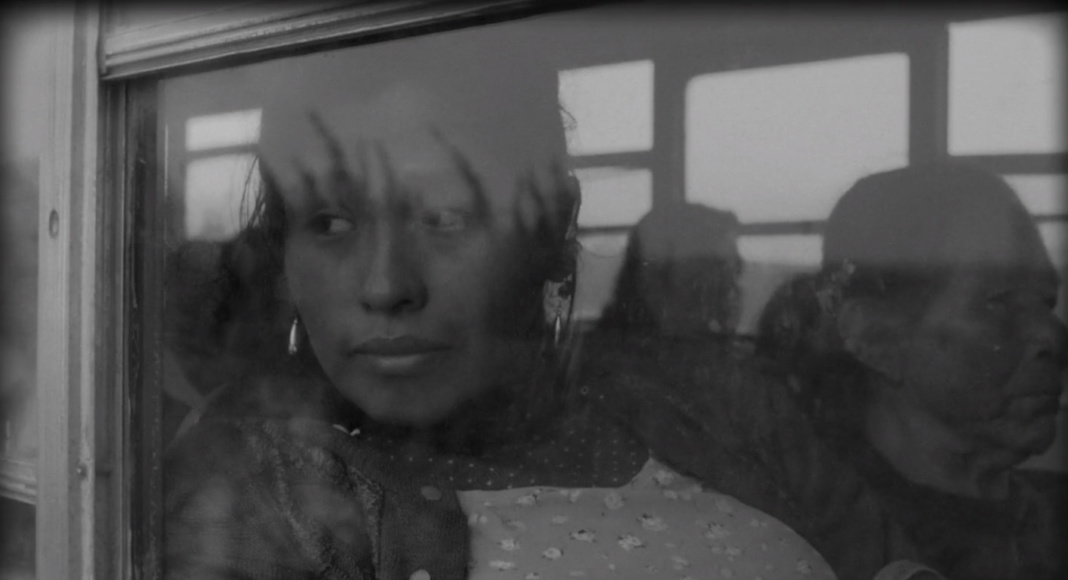

Pamela Mendoza is enthralling as Georgina, a mother who, lacking support or access to healthcare, gives birth in an unofficial clinic and never gets to see her child. Her acute pain and determination to find her child is evoked with sincerity and relatability. Georgina is unrelenting, and, as director Melina León notes, ‘Pamela Mendoza did everything to achieve that performance, even changing her figure to become a pregnant mother in the film’. She portrays a woman taking control of her situation, pooling her resources and searching for opportunities to find the truth, with absolute grace.

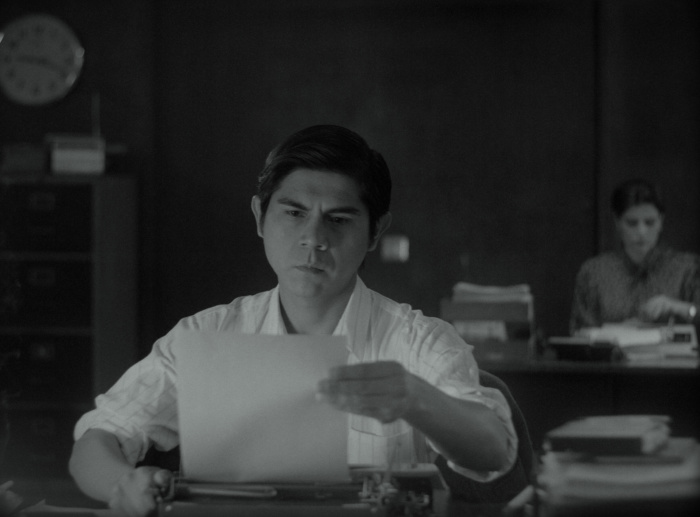

Context is established at the film’s opening, with a montage of newspaper headlines detailing huge inflation, power cuts, curfews and violence attributed to the Sendero Luminoso insurgent group. This montage reflects León’s own introduction into the issue the film centres: her father reported on the illegal trafficking of children as a journalist in Peru in the ‘80s. Three decades later, her father received a phone call from a French woman who explained she was one of the children he had reported on 30 years prior. León decided to mirror this woman’s journey back to Peru from Europe to learn about her past.

But the film is not just an exposé of the scandal of child trafficking and the tragedy of a mother searching for her child. It also conveys the multiple problems of the times. Life is precarious and candlelit for all the protagonists and León manages to weave multiple storylines into a compelling plot by quietly exposing the underlying social, economic and cultural inequalities.

Pedro, the journalist who fights for Georgina’s case to be heard, is caught up in his own stigmatised love story. Georgina’s husband, Leo, is easily recruited by the Shining Path armed group to carry out violent activities. With a baby on the way, no legal ID and having been fired from his job at the market, he’s left with few other options. The voices of Georgina and other indigenous women are ignored by the authorities.

The monochrome effect renders familiar landscapes alien, like the open sea, sand dunes and rocky cliffs of outer Lima. The first time we see Georgina and her husband Leo making the long, arduous walk up the remote hill they live on, it’s hard to tell whether they’re stepping through volcanic ash, sand dunes or mud piles. Their physical remoteness and the distorted views reflect their exclusion from city life and politics.

It’s important to note that three out of four Peruvians affected by the armed conflict were Quechua speakers. This was a racialised conflict, as the film quietly demonstrates.

The community celebrations and dances which Georgina and Leo take part in are dynamically filmed. Leo dances the ‘danza de las tijeras’, in costume, and Georgina sings. The Quechua songs are subtitled, giving an insight into their contemporary relevance. These moments offer Georgina a chance for reflection on her situation. ‘There’s a lot of soul in it,’ León explains, ‘Despite the darkness, there are moments in this film that speak about the many possibilities of life’.

Although the film was shot over just five weeks, León explained that it took years to research the issue and develop the screenplay. This is an issue that people don’t tend to speak about, she told the audience, one which happens particularly to women and overwhelmingly to indigenous women, often sold into sex work in touristy areas of the the Amazon and Cusco. León also emphasised that this story sadly is not relegated to the past, nor is it unique to Peru.

In this vein, although there’s no one clear message in the film, León attests that she wanted to find a link between the many forms of violence we perpetrate on one another.

Canción sin nombre shows how a culture of racism among Peru’s elites allowed for the conflict to reach such heights, and this is epitomised in a horrific act committed against an indigenous woman and the lack of reparations for the crime. While white Peruvians suffer blackouts, increased poverty and horrific headlines, they still find work and general security; Georgina and Leo, on the other hand, find themselves caught up in arduous violence simply through trying to survive.

Song Without A Name will move audiences globally, as it is framed from the survivor’s point of view, relaying how these tragic crimes affect the victims, and highlighting their irreversible effects, regardless of complicity and whether legal justice is served. ‘I just hope that we get to show it to Peruvians soon’, said director Melina León…

Our partners Cine Latino and King’s College London will be screening Song Without A Name online for 48 hours beginning on Friday November 5, 2021 at 6pm. All are welcome, and you can register for free here.

You can also watch the film on Curzon Home Cinema, Vimeo On Demand, Amazon, YouTube, Netflix and MUBI.