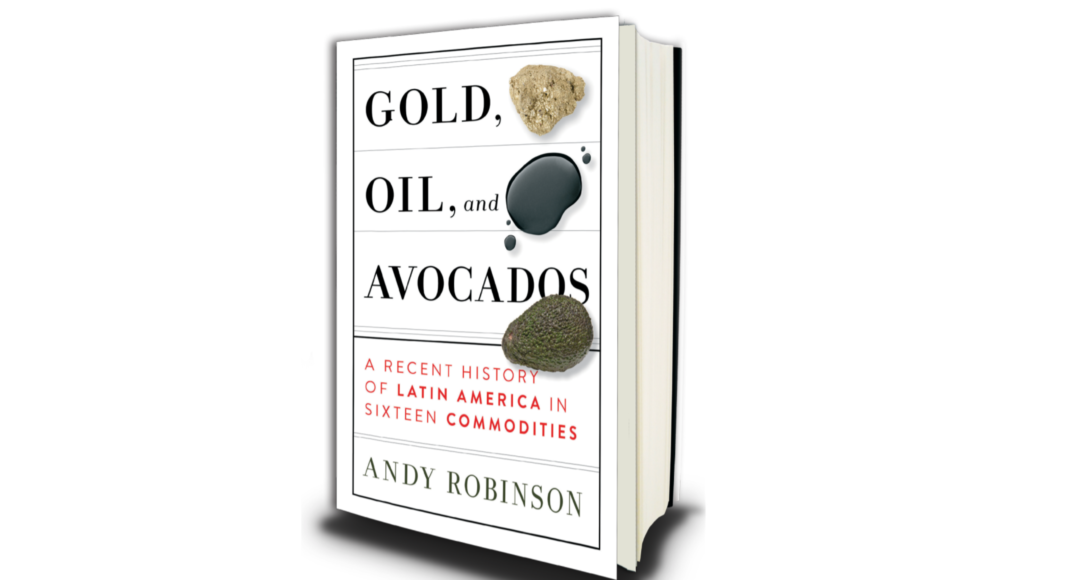

‘Gold, Oil and Avocados, A Recent History of Latin America in Sixteen Commodities’ by Andy Robinson is a detailed account of export extractivism in Latin America, offering rich context.

The past decade has seen major political upheaval in Latin America— from Brazil to Chile to Venezuela to Bolivia—but to understand what happened, ask first where your quinoa and lithium batteries came from…

Inspired by the work of Uruguayan author Eduardo Galeano, who traced Latin American history by exposing five centuries of exploitation in his bestseller Open Veins of Latin America more than five decades ago, Spanish journalist and international reporter, Andy Robinson, chronicles his adventures throughout the region while retracing Galeanos’ routes. He strives to portray the current political and economic dominance in the continent regarding the extraction and export of the region’s most valuable raw materials.

The author visited crop farms in Bolivia; mines in Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, and Chile; and cattle ranches and garimpos in Brazil. He talked with local workers, Indigenous communities, politicians, business owners, and others, allowing him to construct a detailed and well-documented narrative about the economic and social impact of the extraction of 16 sought-after commodities: iron, niobium, coltan, gold, diamonds and emeralds, banana, potatoes, copper, lithium, quinoa, silver, avocados, soy, beef, oil, and hydroelectric power. Robinson gives an eyewitness account of the entire chain of production from the initial extraction to their final distribution in the global market.

Unlike Galeano, who opted for a literary style, Robinson uses his reporting skills to offer detailed depictions of how the exploration and extraction of diminishing natural resources remains a serious and growing threat to the environment. He describes, for instance, how avocado plantations are advancing relentlessly around shrinking lakes and parched soil, given that each hectare consumes nearly 100 thousand litres of water per month.

Although Robinson does acknowledge Galeano’s change of mind 40 years later when he admitted that Open Veins was the work of a young man with no grasp of economics, infected by the dogmatism of the old left; the journalist still opts for an over-simplified and one-dimensional analysis. His narrative reduces everything to two polar opposites: left versus right, and he casts capitalism and imperialism as the sole culprits for exploitation and unscrupulous extraction of Latin America’s resource-rich land. But there’s more to the story; many other historic factors have played their role.

No doubt, Latin America remains at the mercy of the rise and fall of commodity prices, offering cheap labour and huge profit margins to the international market. It is true that the current Latin American right-wing leaders are oblivious to increasing inequalities and far from sympathetic to the environment, indigenous traditions, or sustainable development. Jair Bolsonaro’s cruel behaviour, for instance, could scarcely be more disastrous. However, former progressive leaders also bragged about bringing development and improving the lives of millions of citizens. Allowing people to acquire cell phones and domestic appliances (or jet-skis) is not enough to end poverty, especially when populist, morally flawed, and economically unsustainable measures lead to steadily increasing credit card debt. That’s consumerism, not sustainable growth.

Substantial investment in education, health and basic infrastructure have never been a priority for governments in Latin America. Unfortunately, in Brazil, as elsewhere in the region, ideology has always played second fiddle to bribery, as Robinson points out. It seems that the agenda of social transformation was never a real intention, and was more of an empty and somewhat deceptive campaign promise. And on the rare occasions when good intentions were in play, they should have been accompanied by meticulous studies of impacts on the environment and careful planning in relation to long-term benefits to the local economy.

With its detailed description and rich context, Gold, Oil and Avocados offers valid accounts on how primary export extractivism in Latin America in the past decade has continued to challenge the environment, the local economy and its people, a burden that has been leadened by disastrous government policies. Robinson’s observations confirm the need for the entire region to move towards implementing sustainable smaller-scale production systems and fomenting a more equitable income distribution.

Hopefully, the book will persuade global consumers to minimise the negative impacts of their consumption. It is now well established that environmental destruction and accelerating deforestation in the Amazon are hastening planetary climate change and bringing catastrophic droughts to the Andes and Central America. It’s already happening… and it’s never been more crucial to ask ourselves where those lithium batteries come from before we order the latest smartphone.

Gold, Oil, And Avocados : A Recent History of Latin America in Sixteen Commodities was published by Melville House Publishing last month. You can purchase a copy here.