Carole Concha Bell reviews Alborada Films’ new documentary feature, ‘Santiago Rising’. You can watch her interview with director Nick MacWilliam here.

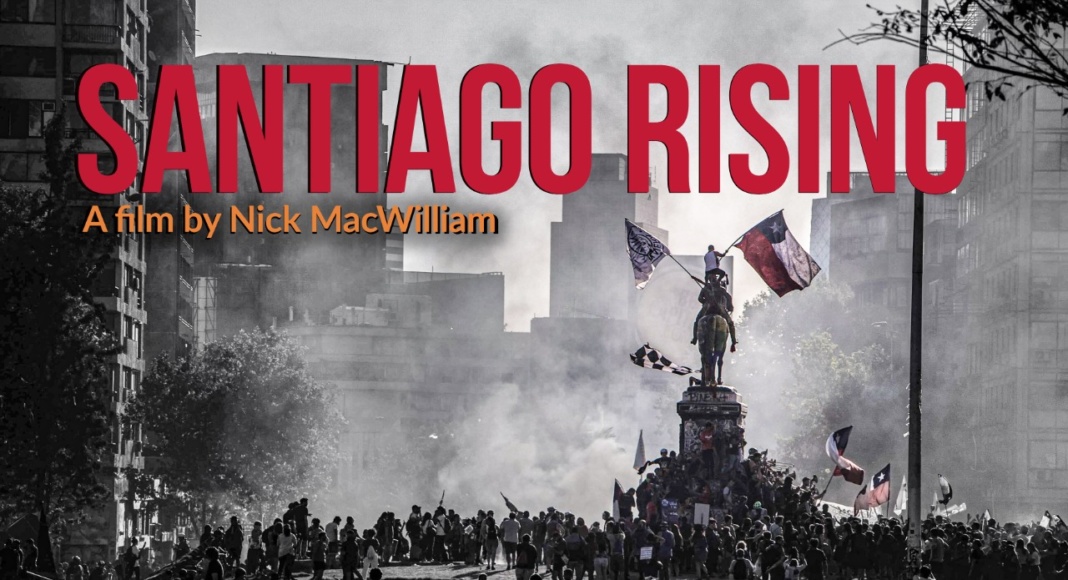

‘I’m not scared.’ remarks an elderly woman as she calmly navigates her way home amid the carnage, bread bag in her hand and handkerchief at the ready in case the tear gas becomes too overwhelming. She’s near Plaza Dignidad in Santiago, as carnivalesque protesters and armed police battle for the heart of Santiago Central’s emblematic Plaza Baquedano (renamed Dignidad). It is January 2020, and protests against extreme neo-liberal policy, installed by the Pinochet regime and managed by successive ‘centrist’ administrations during Chile’s dubious transition to democracy, rage on.

It’s the fearlessness of a generation that have suffered the direct effects of living in Chile’s neo-liberal jungle that really comes across in Nick McWilliams’s first documentary, ‘Santiago Rising’, now available now to stream/download on Vimeo.

‘I wanted to capture what was happening in Chile and to pay homage to the strength and commitment of the Chilean people. They are taking on neo-liberalism and a militarised state with stones and trumpets. This is a lesson for the rest of the world, we can learn so much from them. There are no political parties coordinating this, yet Chileans are on the street every single day. Independent media networks have been fundamental to the process, as have the medical brigades, musicians, and artists. To witness the sheer scale of how grassroots groups were organising was fascinating,’ says McWilliam in interview with Latin American Bureau.

The documentary takes us on an epic journey through the hearts and minds of those at the protests. ‘We have nothing to lose’ is a repetitive mantra expressed by interviewees that range from recently politicised young people, to housewives and old school activists such as feminist Beatriz Batasew.

What the film manages to do is place the viewer at the heart of the action. By focusing on the events as they occur, we manage to get a glimpse of the violence inflicted upon peaceful demonstrators by Chile’s brutal police force Los Carabineros, plus the euphoria of the crowd as they unite against oppression, both historically and in real time.

‘There were mounted police charging directly at me. One [policeman] hit me on the head. I was clearly press of some sort. The tear gas was horrible and there was a real sense of aggression and intimidation. At the Mauricio Fredes memorial I had the feeling they were shooting at the camera to destroy it. They were attacking everybody; at times it was scary, and I saw them using excessive force towards protesters, yet there was a real sense of unity. Men and women (the Primera Linea) fought off the police and formed a human barrier to protect everyone from the violent repression.’

McWilliam states that it was a combination of curiosity and being in the right place at the right time that allowed him to capture emblematic moments at the now historic protests. One harrowing scene takes place at the funeral of Mauricio Fredes, a much-loved member of the frontline or primera linea; a group of men and women who act as a form of human shield to protect more vulnerable protesters such as the elderly, against the might of Chile’s heavily armed security forces, often risking injury and even death. In one scene, the funeral of Fredes is unjustly repressed by the carabineros. The naked fury and impotence of the attendees makes for tough viewing.

What makes this documentary stand out in the cacophony of voices commentating on the uprising is its focus on the arts. McWilliam skilfully narrates the history of the art embedded in Chilean protest traditions, for example in song and performance in the viral Las Tesis performance ‘Un violador en tu camino’; in political street art via the mural brigades (Brigada Ramona Parra) in Allende’s Chile; in the more contemporary songs of Los Prisioneros whose famous ‘El baile de los que sobran’ has come to epitomise the plight of those left behind by a cruel system in which the poor get poorer at the expense of the rich elites.

The innovation and humour of the protests permeates the mood of the film, as bright costumes and classic protest songs such as Victor Jara’s anthem ‘El derecho de vivir en paz’ dominate the soundscape. Before the pandemic forced protesters into retreat, Santiago’s centre had become a living art gallery. Mosaics, murals and sculpture adorned the main avenues and made global headlines, all neatly captured and interpreted by the film.

By examining the role of Chilean music, street art and dance alongside the socio-political explosion, we get a glimpse of how culture and politics have become symbiotic against a backdrop of repression and the criminalisation of protest.

What this important film imparts is not just a glimpse into the uprising, but important lessons for all activists and grassroots movements. The walls of Santiago may have been stripped clean by a right-wing government hellbent on quashing the voice of dissent, but the unity of the Chilean people in their sheer will and determination to push for real change will remain with the viewer.

Santiago Rising is available now to stream/download on Vimeo.