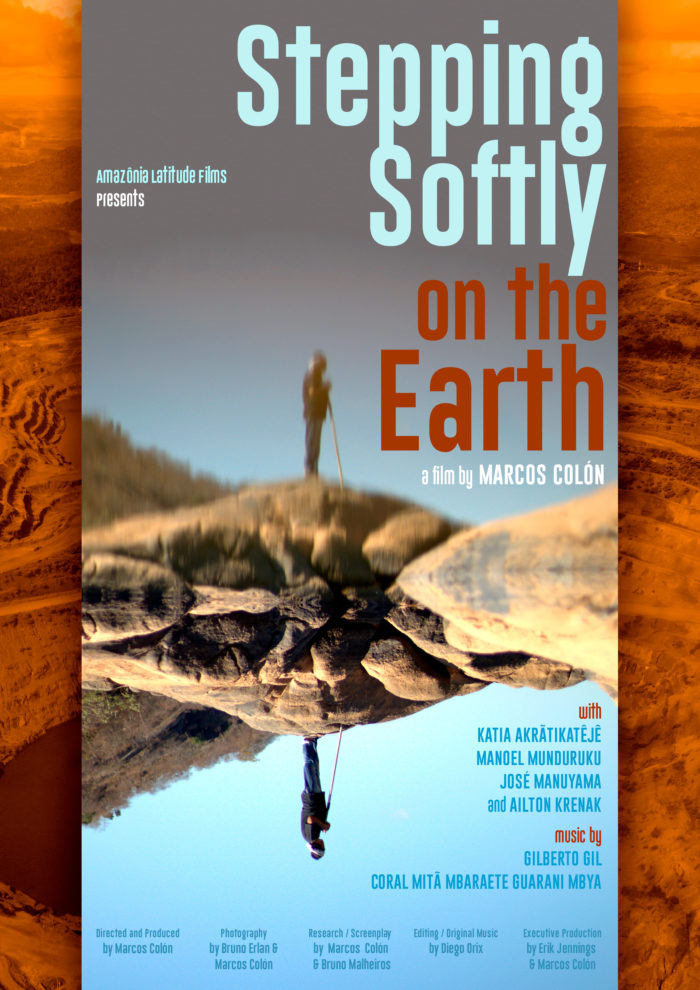

Marcos Colón describes ‘Stepping Softly on the Earth’, a new film which he has directed, due for release in September 2022.

The film ‘places in the center of our ways of thinking, those who have been historically pushed to the edges of thought. They are the indigenous peoples, the protagonists of a possible future, since, as Krenak would say, ‘the future is ancestral’ and we need to learn with it to step softly on the earth.’

We were on the BR 155, a few kilometers away from where it crosses the Trans-Amazonian highway, when a meat packing company sign announced our entrance into ‘a world of sun and pasture’. The view on both sides of the road was soon taken over by enormous farms. The arid environment wrapped the febrile landscape in a permanent cloak of heat. A few kilometers ahead, we saw a beautiful Brazil nut tree, exuberantly elegant, a silent witness, an ancestral presence, forgotten by history in the middle of a field, calling the cows to gather in its shade.

The colors of the scene invited us to stop the car in the only place with a hard shoulder, right next to the entrance to a farm. We took the drone out of its case, and started guiding it towards the tree, to capture the scene. Even before the drone gained altitude, a car, which was about to enter the farm, stopped when it caught sight of us. The driver stared at us for a long time. Uncertain what to do, we quickly landed the drone, as at that moment, we felt threatened. In this region of the Amazon where leaders and defenders of human rights and nature are frequently killed, a car stopped in front of you can mean much more than an intimidating look. We didn’t record the scene, but we felt that we needed to tell this story, and others – of an Amazônia suffering under a death project which produces fire, smoke, contamination, and blood.

Extensive livestock production, which supplies the meat packers we saw near the start of the highway, and numerous others spread across the South and South-East of Pará, has steadily penetrated the various parts of the Amazon, spreading deforestation and the burning of forests.

Nevertheless, we are in the Amazon and the life of the forest still calls the living to a dance against this party of greed and destruction.

A few kilometers away from the silent Brazil nut tree witness, we went to meet a group of people who are key to the harvest of the nuts of this region. They come from one of the most severely affected indigenous territories in Brazil. This now consists of a tract of forest found marooned between the cattle farms, power lines, railways and streets, flowering like a solitary rose.

This is a story that must be told. It is the story of the chief of the Akrãntikatêgê people, Kátia Silene, who many wished to silence, but whose voice resonates with the strength of long-established roots. Every day, Kátia confronts the Vale mining company, which, in the first three months of 2021, in the midst of the second wave of the new coronavirus pandemic, posted a profit of US$ 5,546 billion, a 2,220% increase on the same period in the previous year. Profits so often followed by numberless deaths. Kátia is not intimidated. Every word she says broadens our ways of perceiving the world.

The forest lay down

It was in the Munduruku lands surrounding Santarém, still within the Brazilian Amazon, that we would again encounter the daily tension facing those who insist on living their lives in the Amazon. After much discussion as to whether we should go to witness the latest felling of trees – in an area where intimidation and threats occur every day – at around 1:00 am we decided that we had to face the danger and go.

We slept for a few hours and then by a back route arrived at the recently deforested area. The situation was so tense that our guides from the local area, fearing the worst, remained in the car. The trail of destruction was hidden by a carpet of morning mist soon burned away by the sun’s rays. We were on indigenous land that had been invaded by soy farmers.

We know that the area planted to soy in Brazil grew 166.5% between 1999 and 2018 and that soy, like mining for iron ore and other commodities, continued unchanged by the economic decisions of most recent governments in Latin America, irrespective of their place on the political spectrum. However, the statistics do not come close to capturing the real violence experienced by those who find themselves in the way of this expansion.

Only hours ago, chains stretched between tractors had dragged down an immense area of forest. The smell of fallen trees was everywhere – along with the fear. Nobody felt safe enough to leave the car, but the urgency of the scene, of the need to record it, helped us overcome this fear. Finding the forest demolished, and with the silent faces of people who no longer feel safe on their own land, we felt as we had done when we met the gaze of the driver that had stopped in front of us by the solitary Brazil nut tree. Yet we knew that we had to tell this story.

From there, from that climate of tension, another character will appear. This story will be told by a tribal chief that who dares to resist the threats and invasions of his lands, Cacique Manoel of the Munduruku people.

The rates of deforestation, the number of forests being burned down, as well as the expansion of monocultures and mining, are not only accelerating in the Brazilian Amazon. The rivers contaminated with the waste of economic activities such as mining are also not limited to a single country – albeit one whose government especially encourages the pillage of material and energy while eroding all the legal guarantees that still ensure some security to the peoples and traditional communities as well as to the land under environmental protection.

Capitalism as a war on Amazonian peoples is also a project of distinct governments that encourage capitalist barbarity in the region, be it in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela, the Guianas, Suriname or Colombia – the Nations whose territories abut the Amazonian biome.

Transcending the maps

We travelled through some of these countries, we criss-crossed the frontiers invented by Nation States, we met indigenous peoples and nationalities not limited by the lines drawn on colonial maps. Amazonian ancestry is connected in so many ways and our histories entwine in so many plots that for the people of these lands, the State becomes a coarse invention of a grotesque and exclusive project, that has always ignored other possibilities of being for the native peoples.

Perhaps that is why the violent expansion of capitalism in the Amazon is always backed by the State. The greatest and most real connection between so many peoples, cultures, and communities is not the State, but the Amazon River, and it was through the meanderings of this river that we arrived at an Amazonian image-in-common – a third story that needed to be told.

On the Peruvian side, we found a tributary of the Amazon, the Nanay River and a city erected upon it: Iquitos. The Nanay River is a water source providing for the city of Iquitos, but as in so many other places in the Amazon, mining and oil exploration don’t seem to care about that. Here, from the prow of a boat, José Manuyama, el hombre del agua (the water man), Kukama descendant and a member of the Water Defense Committee of Iquitos, tells us his story and makes us rethink our own, his knowledge nourished by the life of the river.

Our crude sketches on paper gained the contours of reality with the testimony of those who confront capitalist barbarity in the Amazon. You cannot pass through these lands without, at some point in time, coming across a person who for 40 years has told stories of the Amazon across the radio waves: broadcaster Mara Régia. The strength of her voice will guide us in this narrative.

Having finished filming, from Peru to Colombia to Brazil, from Santarém to Marabá, from Iquitos to São Paulo, we then began editing and, for a long time we were puzzled. There was a hiatus, something missing… Of some things we were certain: that we were standing by the people that confront the system of death and destruction that is capitalism in the Amazon; that we could convey the power of feeling in each voice. But then we started to change the terms of engagement and the depth of it all. We needed to listen more than speak, feel more than define.

To delay the end of the world

In reality, we were standing face to face with indigenous stories that could delay the end of the world. This seemed to be the most beautiful expression of the force that moves us. Perhaps, for this, we would turn to the thoughts of Ailton Krenak and his voice would sound sweet to ears full of uncertainties.

Like an ancestral echo, Ailton’s way of thinking defined an important step in the film: we spoke of three different Amazonians, three stories of struggle, but our characters are not defined only by the terms of those that wish to invade their lands: they are more than that, much more than that.

Each offers, in their own way, alternative horizons, a way out of the systemic chaos in which we live. Their ancestries point to a different way of seeing the world, a particular way of feeling and thinking with the Earth. Through their own voices and the territory they embody, each character invites the viewer to make a complete change of perspective: to see life, where it generally is not seen; to hear voices, where they are generally not heard; to feel the sensation of stepping softly on the earth, an experience that the concrete of the cities, and the hours told by clocks have taken away from our lives.

Different paths cross, distinct worlds draw closer together and form a story that needs to reach us. The indigenous Kukama (José Manuyama), who lives in the Peruvian Amazon, close to the city of Iquitos, on the banks of the Nanay River, a river contaminated by mining and the activities of the petroleum industry. The Munduruku chief (Manoel), confined in his own ancestral territory, in the west of the state of Pará, Brazil, by the rapid expansion of the soy monoculture. The chief of the Akrãntikatêgê people (Kátia), of the Mãe Maria indigenous land, located close to the city of Marabá, also in Pará, in the Brazilian Amazon, in a territory scarred by mining, by highways, and by power lines. Each one is the protagonist of other possible stories for a world anesthetized by a single story.

For all these reasons, Stepping softly on the earth is not meant just as a warning against the capitalist history of war on the Amazonian peoples, which has just entered its most frightening chapter. The film intends to be much more than this! It wants to speak of other horizons in the meaning of life, where the protagonists will be people that, even today, carry an ancestry capable of showing us ways of being in the world that are completely distinct from those we have chosen as a western society, and that are leading us to ruin.

More than denouncing, the film announces, as it hoists aloft and places in the center of our ways of thinking, those who have been historically pushed to the edges of thought. They are the indigenous peoples, the protagonists of a possible future, since, as Krenak would say, ‘the future is ancestral’ and we need to learn with it to step softly on the earth.

Stepping Softly on the Earth

Direction and Production: Marcos Colón

Script: Marcos Colón & Bruno Malheiro

With Katia Silene Akrãtikatêjê, Manoel Munduruku, José Manuyama and Ailton Krenak

Photography: Bruno Erlan & Marcos Colón

Editing & Original Score: Diego Orix

Executive Producer: Erik Jennings & Marcos Colón

Country and year of production: Brasil, Peru and Colombia / 2022

Coproduction: Amazônia Latitude Films

Duration: 73 minutes

Release: September/2022

Marcos Colón leads the Portuguese Program in the Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics of Florida State University and is the director of the documentary “Beyond Fordlândia”. Colón is a doctor of cultural studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.