Main video: President Desi Bouterse casting his vote on Monday 25 May at a polling station in Paramaribo, ‘President Bouterse has fulfilled his civic duty’. Nationaal Informatie Instituut. YouTube. 25 May 2020.

Suriname, the smallest country in South America and with a population of 550,000, does not usually make international news headlines. However, the recent parliamentary election was the first to take place in the region since the coronavirus pandemic began. Not only this, but it appeared that one of the last remnants of the military coups and juntas of the 1970s and 1980s could be swept away, meaning that Desi Bouterse would have to relinquish his 40-year grip on power. With on-going economic trouble, corruption scandals and recent offshore oil discoveries, 2020 is a key year for the former Dutch colony.

Who is Desi Bouterse?

Desi Bouterse, now 75, first came to power in 1980, as leader of the so-called Sergeants Coup when 15 military officers overthrew Henck Arron, the first leader of Suriname since its independence from the Netherlands in 1975. For the next seven years, he was the de facto ruler of the country as Chairman of the National Military Council. After losing the 1987 election, he remained a prominent figure during the 1990s and 2000s and finally managed to win power democratically in 2010 as head of the Mega Combination coalition, narrowly winning re-election in 2015.

Bouterse has been no stranger to controversy over the past 40 years. In 1982 soldiers killed 15 of his opponents at Fort Zeelandia, a fortress in the capital Paramaribo, in an event that has become known as the December Murders. Bouterse claimed the victims were shot escaping the building (at the time his headquarters) and he has always denied personal responsibility, although in 2007 he did admit ‘political’ responsibility for the murders.

The December Murders and Massacre in Moiwana:

Despite being granted amnesty by the National Assembly in 2012, in December 2019 a military court found Bouterse guilty of ‘overseeing’ the murders and sentenced him to 20 years in prison once the amnesty ruling was overturned. However, no arrest warrant was issued because under Surinamese law an arrest cannot be made until all appeals have been exhausted, a long process already delayed because of coronavirus.

Bouterse was also connected to a massacre carried out by his forces of at least 39 people in the village of Moiwana in 1986 during the Suriname Guerrilla War (1986-1991). Moiwana was the home of Ronnie Brunswijk, Bouterse’s former bodyguard and leader of the rebel army. The conflict, mainly in the remotest parts of the country, arose following a dispute between the pair.

Drugs and crime

In 1999, a court in the Netherlands found Bouterse guilty in absentia of trafficking cocaine into the country. Bouterse has always denied the charge and his election victory in 2010 conferred on him presidential immunity, meaning that, despite an outstanding Interpol arrest warrant, he could not be extradited to the Netherlands. Once he ceases to be president, Bouterse’s immunity will end and he may face arrest in countries that have extradition agreements with the Netherlands.

Several of his relations also have criminal connections. Desi’s son, Dino Bouterse, is currently imprisoned in the USA after being found guilty of offering Suriname as a base to Hezbollah and on drug trafficking charges. Also, soon after assuming the presidency in 2011, Bouterse pardoned his foster son, Romano Meriba, who was found guilty of murdering a Chinese man and throwing a grenade at the Dutch ambassador’s residence in 2005.

With such a murky past, how did Bouterse become so popular in Suriname? In a style similar to Hugo Chávez and the populist leaders of today, he portrays himself as a man-of-the-people and loveable tough guy. He was respected for founding the National Democratic Party (NDP) in 1987, which, more than any other party, managed to draw support from the many different ethnic groups in the country – Indian, African, creoles, Javanese and indigenous communities. After his 2010 election, Bouterse’s government initially embarked on massive spending on social welfare, healthcare and infrastructure projects, while income from exports of bauxite, gold and timber – the country’s main exports – remained consistent.

Economic problems and corruption scandals:

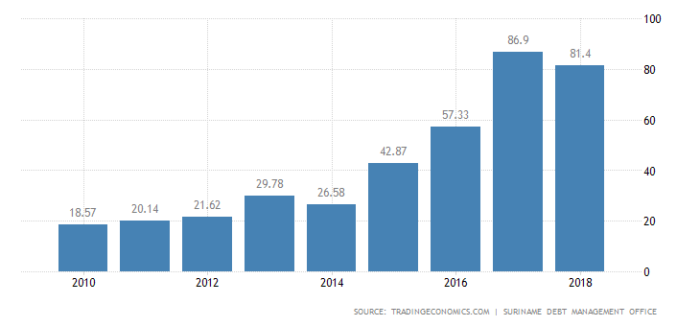

Government debt as a percentage of total GDP. Image: Trading Economics. Suriname Debt Management Office.

Recently, however, economic problems and corruption scandals have mounted up, with fears emerging that the country could default on its debt payments. Economic mismanagement and overspending have had a profound effect while the prices of gold and bauxite have fallen. Suriname recently received $1.5bn in Chinese loans but this has proved insufficient to resolve the crisis. In 2018, government debt reached nearly 81.4% of GDP, inflation rose from 4.3% in July 2019 to 17.75% in March 2020 and the currency exchange rate was fixed – causing protest from the country’s banks.

$100m recently went missing from the Suriname Central Bank. It was found that the institution’s foreign exchange reserves had been used to import food, pay foreign debt and to strengthen the Surinamese dollar. A corruption inquiry was established and Robert van Trikt – the bank’s governor – was fired and arrested. Charges were also brought against Gillmore Hoefdraad, the Finance Minister and a Bouterse ally.

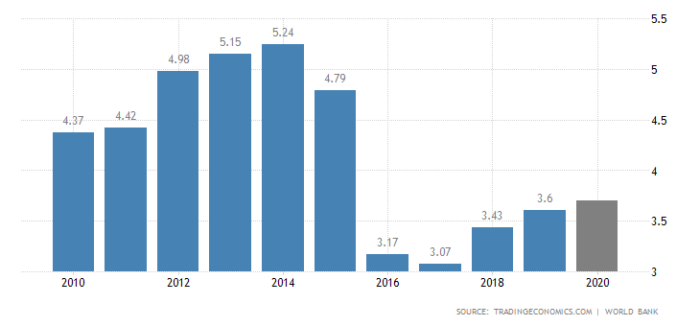

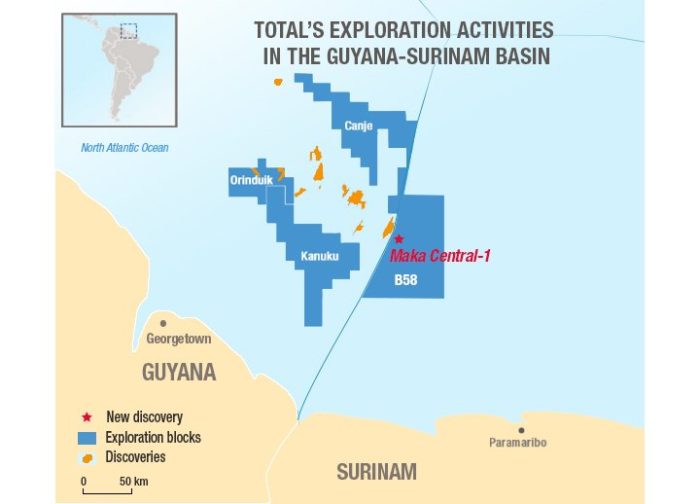

A glimmer of economic hope recently emerged with the discovery of offshore oil reserves in January 2020. According to Staatsolie (a state-owned Surinamese oil company), the country has oil reserves of around 100m barrels. But, the recent global collapse in oil prices and ongoing low demand means that it may take a long time before the recent oil discoveries pay dividends.

2020 Parliamentary Election:

Election Day – 25 May – took place with observers from the Organization of American States (OAS) and CARICOM (Caribbean Community). The EU, however, decided not to send a mission as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. Polls favoured opposition parties but Covid-19 made political campaigning harder, especially in hard-to-reach inland. The curfew was briefly lifted however to allow voting and the 10-person OAS mission reported a fair election with 70% turnout. However, there were reports of some voting irregularities and disorder at polling booths.

17 parties had registered to run against the NDP and Bouterse, meaning that a coalition would likely be necessary to beat Bouterse. But, the post-election political landscape was muddied because a recent electoral reform prevented parties from forming pre-vote coalitions, a common occurrence in previous elections, with no one party ever winning an absolute majority since 1987.

Observers reported that the process of declaring results had been slow. Vote counting was briefly suspended on 26 May as a result of fatigue and was again halted after the number of coronavirus cases increased in the country.

The Electoral Office said it would be at least two weeks before the count could be finalised. In the end, it took until the evening of 4 June to announce the results. VHP (the Progressive Reform Party) won 20 seats (39.5% of the vote) compared to 16 seats (23.9%) for the NDP.

Earlier, on 30 May, a coalition was announced led by VHP along with ABOP (General Liberation and Development Party – led by Ronnie Brunswijk) NPS (National Party of Suriname) and PL (Pertjajah Luhur).

This coalition obtained 33 seats in the National Assembly – a majority, but one seat short of the two-thirds majority needed to elect a president when the new parliament convenes in August. It is led by Chan Santokhi – the ex-chief of police who lead the December Murders investigation and is a critic of Bouterse. Generally Centre-Left, the coalition joins political parties who have traditionally appealed to Afro-Surinamese, Indo-Surinamese and Javanese Surinamese communities.

While Bouterse was reported to have lost his own National Assembly seat in Paramaribo to the VHP candidate, the NDP has asked for a recount in some areas. In contrast, opposition parties accused Bouterse of obstructing the formation of a new legislature and delaying the vote count.

All these events came shortly before strict measures were introduced to combat a spike in Covid-19 cases. From zero cases at the end of May, there are now 80 cases in the country. It seems that Bouterse’s grip on power has come to an end, but with coronavirus still active and a pre-existing economic crisis, Suriname confronts many challenges in the days to come.