- The United States and Brazil have been conducting closed door negotiations to broker an Amazon rainforest protection agreement — with the U.S. and other nations tentatively to provide significant funding, and Brazil possibly agreeing to pragmatic measures to end deforestation.

- However, as the global Climate Leaders Summit progressed today, it became apparent that those talks are likely stalemated, with no deal announced, nor likely anytime soon.

- Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has made it clear that Amazon conservation is dependent on a big financial investment by the United States. However, Amazon deforestation continued soaring through March, even as critics offered substantial proof Brazil is insincere in its environmental commitments.

- For example, new federal rules make it nearly impossible to collect fines for environmental crimes. Also, Brazil has made suspect adjustments to its Paris Climate Agreement carbon reduction targets, allowing it to meet its goals on paper, even as it continues cutting down forests and releasing greenhouse gases.

Banner image: A pre-Bolsonaro IBAMA environmental agency raid on an illegal Amazon timber harvest. New rules under Bolsonaro make fines for environmental crimes nearly impossible to collect, which has resulted in a protest by 400 IBAMA personnel. Image courtesy of IBAMA.

This article was published by Mongabay on 22 April 2021. You can read the original here.

Despite ongoing closed door negotiations between the U.S. administration of President Joseph Biden and the government of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, no headway has yet been announced on any agreement to end Brazil’s assault on the Amazon rainforest. Even though the final outcome is still unclear, the talks seem headed for stalemate, despite the fanfare and pledges sounded at today’s online Climate Leaders Summit.

In his speech to the summit today, Bolsonaro changed his tone and refrained from attacking foreign governments, as he has frequently done in the past. Instead, he announced his administration’s new commitments on deforestation and zero carbon emissions, detailed below. He also used half of his speech to ask for money for the environmental achievements Brazil made over the last 15 years — accomplishments he has been actively reversing for two years.

In the past, Brazil has often played a key role in such summits, but Bolsonaro’s remarks today gained little notice by international media, though they did rouse critics. Marcio Astrini, executive secretary of the Observatório do Clima, a coalition of civil society bodies concerned with the environment, commented: “Brazil leaves the summit as it entered it: discredited. The current government has turned Brazil into a pariah, excluding itself from an agenda in which we were once protagonists and that we should be leading.”

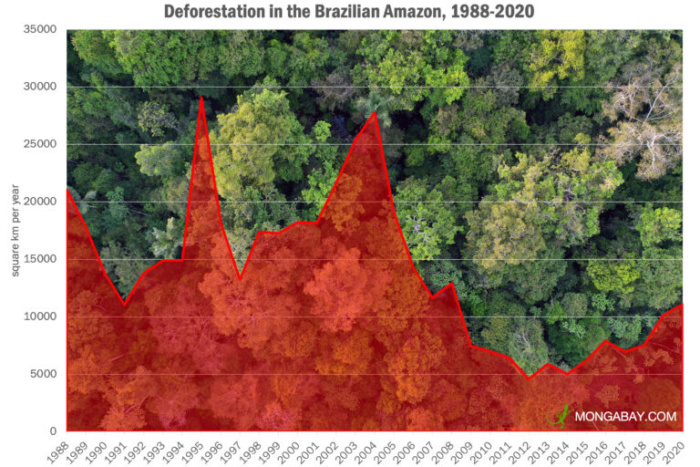

Meanwhile, Amazon deforestation — mostly conducted by land grabbers, agribusiness and cattle ranchers — surges and remains dire. On 19 April IMAZON, a non-profit organization, published its Brazilian Amazon deforestation data for March of this year: 810 square kilometers (313 square miles) of forest was cut in that month alone, more than twice the area lost in March last year and the worst result in ten years.

This brief report highlights the enormity of the task faced by President Joe Biden who on the campaign trail promised to mobilize US$20 billion in private and public money to stop the “tearing down” of the Amazon.

In recent days, Bolsonaro has tried to reassure the Biden administration that he can reverse the tremendous momentum of the deteriorating deforestation situation, and so should be entrusted with the money. In a dramatic change from earlier defiance, Bolsonaro sent a conciliatory letter to Biden in mid-April, stating his commitment to eliminating illegal deforestation by 2030. He added, however, that this could only be achieved with “substantial resources” from the international community, particularly the U.S. government.

In similar fashion, Brazil’s environment minister, Ricardo Salles, said in the same week that the Bolsonaro administration was finally prepared to accept the goal agreed to by Brazil under the Paris climate accord to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 (instead of 2060), but only if it received US$10 billion annually in foreign aid.

In the ongoing negotiations between the two nations, the U.S. then publicly made clear that it was unwilling to hand over money in advance without clear assurances of precisely how the funding would be spent to curb deforestation.

Thus, it seems the U.S.-Brazil Amazon negotiations are at an impasse. The reason: despite Bolsonaro’s and Salles’ reassuring comments, facts on the ground tell a very different story: the Bolsonaro administration has continued with (or perhaps even intensified) its offensive against the environment.

Amazon and climate change sleight of hand

In the week Bolsonaro sent his letter to Biden, his environment ministry changed rules for levying fines for environmental crimes, hindering their payment. Inspectors will no longer be able to impose fines, but will need approval first from their bosses, in a complex administrative procedure. Over 400 IBAMA environmental agency staff sent an open letter to the institution’s president, Eduardo Bim, expressing their perplexity with the new norms, saying that it has brought the fine system to a standstill across Brazil. It’s difficult to imagine how deforestation can be combatted under such conditions, say critics.

Environmentalists are also skeptical of Salles’s 2050 Paris commitment, pointing to a recent government sleight of hand to avoid meeting Brazil’s greenhouse gas reduction goal as originally pledged under the Paris Climate Agreement. In December 2020, the administration quietly changed its calculation for its 2005 emissions, the baseline upon which the nation’s target NDC (nationally determined contribution) was calculated in the Paris accord — raising the 2005 baseline from 2.1 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions to 2.84 billion. By increasing its 2005 estimated baseline, Brazil is now promising emission reductions of 37% by 2025 and 43% by 2030, while in fact, it will be making much smaller real emissions cuts than first pledged. Simply put: by moving the 2005 goalposts, Brazil can appear to make big emission reductions, some of which will exist only on paper, even as the Amazon continues to burn and be deforested.

Calling the baseline alteration “a carbon trick maneuver,” six young climate activists, backed by seven former environment ministers, are now suing the Brazilian government. Txai Surui, a 24-year-old activist and one of the plaintiffs, said in a statement posted on Twitter by her environmental group, Engajamundo, that the government is “flagrantly violating the Paris Agreement, which only allows countries to increase the level of ambition of their NDCs (nationally determined contributions), not to reduce it.” Another of the plaintiffs, Marcelo Rocha, added: “This ploy is a threat not only to young Brazilians but to the whole planet.”

Anders Haug Larsen, head of policy at Rainforest Foundation Norway, is equally outraged. He told Mongabay: “By recalculating its baseline emissions, Brazil has managed to give itself a free pass to dramatically increase emissions. The new NDC… allows Brazil to emit 3.4 gigatons more CO2 over the next decade than its previous climate commitment did. As most emissions stem from deforestation, this will enhance the already critical situation for the rainforest.” These extra emissions entering the atmosphere between now and 2030 — equivalent to more than half of U.S. emissions of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2019 — will make the carbon reduction challenge facing the world even more difficult.

However, according to the Bolsonaro government, Amazon deforestation concerns are all in the past — another sleight of hand. Earlier this month, General Hamilton Mourão, Brazil’s vice president and the president of the Bolsonaro-founded National Council of Amazônia Legal, published Plano Amazônia 2021/2022 in the official gazette. In this declaration, the Bolsonaro administration for the first time ever set an Amazon target for itself — it plans to reduce the rate of deforestation by the end of 2022 to the average level seen between 2016 and 2020, which was 8,700 square kilometers (3,360 square miles). Mourão announced this goal as a response to those criticizing Brazil for the runaway deforestation recorded over the last two years.

Once again, closer examination reveals that the goal isn’t what it seems. Observatório do Clima points out: “When Bolsonaro came to office [in January 2019], annual deforestation in the previous year [2018] had been 7,500 square kilometers (2,900 square miles). He increased it by 48% to 11,088 sq. km. (4,281 sq. miles) [in 2020]. In other words, General Mourão wants to be applauded for promising to bring down deforestation by the end of the [Bolsonaro] government to ‘just’ 16% higher than it was at the beginning of the government.”

Failure to consult stakeholders

NGOs and Indigenous organizations in Brazil say that the Bolsonaro government cannot be trusted and that they must be involved in any Biden-Bolsonaro Amazon deal (negotiations so far have only been held between the two nations behind closed doors). In a letter sent to the U.S. government on 6 April, 205 civil society organizations warned:

It is not sensible to expect any solutions for the Amazon to stem from closed-door meetings with its worst enemy. Any project to help Brazil must be built from dialogue with civil society, subnational governments, academia and, above all, with the local communities that know how to protect the forest and the goods and services it harbors. No talks should move forward until Brazil has slashed deforestation rates to the level required by the national climate change law and until the string of bill proposals sent to Congress containing environmental setbacks is withdrawn.

Representatives of these bodies, skillful in their use of social media, say they are taking on a new role, talking directly to members of the Biden administration, who, they note, are young and hyperpolitical, very different from the technocrats of the Obama days. When John Kerry, Biden’s climate tsar, applauded Brazil’s “recommitment” to ending illegal deforestation, he was flooded with tweets from these activists, saying that the Bolsonaro administration couldn’t be trusted.

Indigenous organizations too have been active, with eight leaders speaking online on 12 April to Jonathan Pershing, the U.S. official in charge of the Amazon negotiations, and to U.S. ambassador Todd Chapman. According to Climate Change News, Dinamam Tuxá, the coordinator of APIB (Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples Articulation), asserted: “There is no dialogue with the Indigenous peoples of Brazil. That’s not because the Indigenous people refuse to speak, but because Brazilian government policy does not allow for this to happen… the Brazilian government is not worried about Indigenous peoples and protecting the forests.”

Many Europeans are also unhappy with the escalation in deforestation.

E.U. Environment Commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius told Brazilian officials in early April: “The E.U. and the international community are expecting Brazil to show a much higher level of ambition.” He added that deforestation must fall sharply in Brazil. With the E.U. expected this summer to introduce legislation to eliminate forest degradation from its commodities supply chains, his comment was seen by analysts as a warning to Brazil that it could face a trade boycott unless it takes action.

Catholic investors are also worried. At the end of March the Catholic Bank für Kirche und Caritas in Germany, along with the Brazilian bishops’ Commission on Integral Ecology and Mining, and the Global Catholic Climate Movement, sent a letter to President Bolsonaro, urging him to do more to protect the Amazon. It was signed by more than 90 Catholic organizations and congregations in at least 17 countries. It read in part: “As Catholics and citizens of this world, we are extremely concerned about the ongoing destruction of the Amazon forest,” and called for a range of measures, including much stricter enforcement of environmental legislation.

Aware of a probable impasse in the Biden-Bolsonaro talks, Brazil’s state governors have been developing their own Amazon initiatives. Twenty-three of Brazil’s 27 governors have formed a bloc called the Governors Coalition for the Climate and have written, but not yet sent, a letter to Biden in which they express their “awareness of the global climate emergency.” It continues: “Our states possess funds and mechanisms created specially to respond to the climate emergency, available for the safe and transparent application of international resources, guaranteeing rapid and verifiable results”.

Despite surging national and international outrage over Brazil’s failed environmental policies, it seems clear, according to many analysts, that the Bolsonaro government hasn’t yet taken onboard that the climate crisis, particularly as it impacts the Amazon rainforest, is a key issue facing Brazil in its foreign diplomacy.