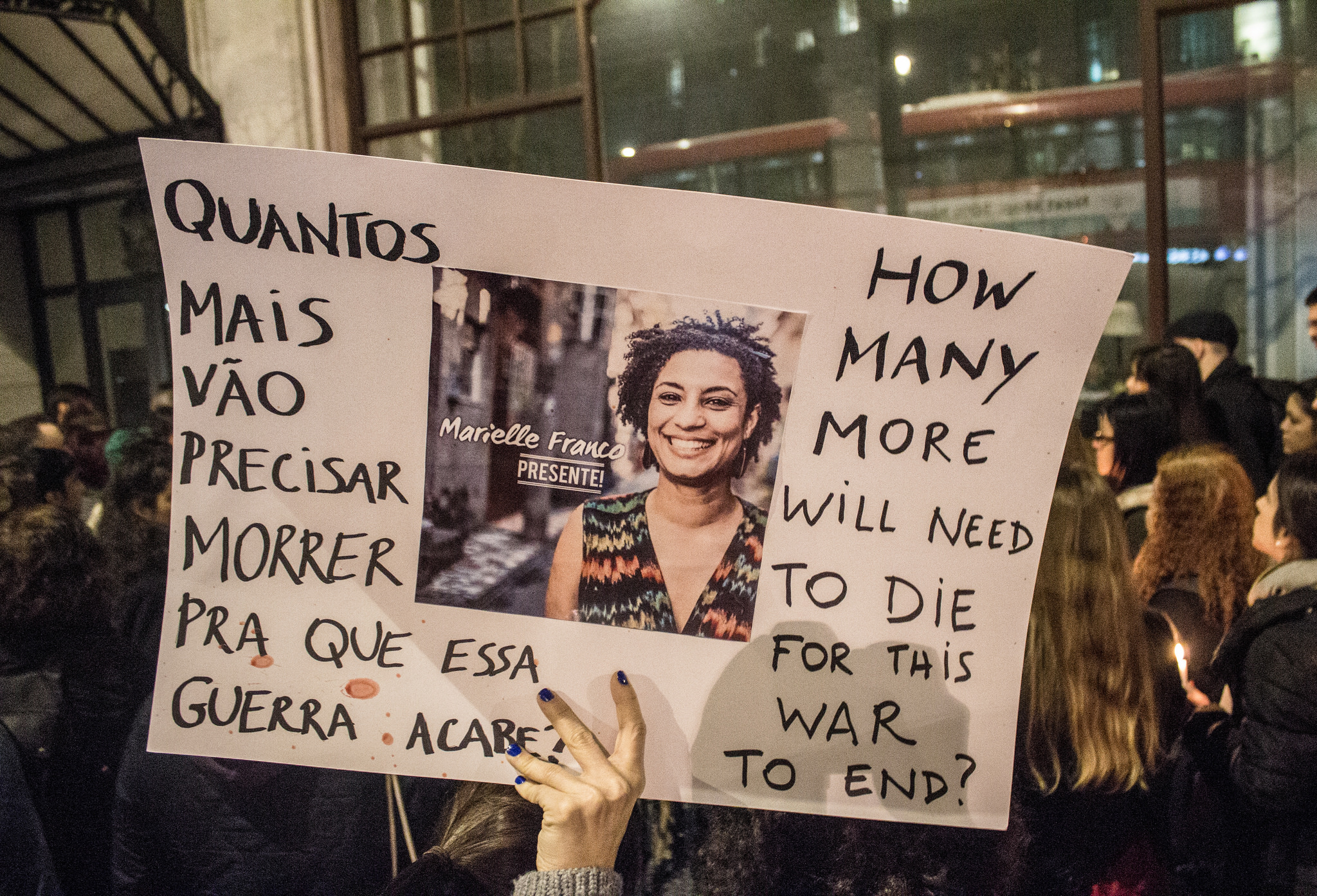

22 March 2018. Marielle Franco was executed with four bullets. One each for racism, misogyny, homophobia and impunity.

By killing Marielle, the assassins eliminated not just a politician elected on the PSOL ticket to the Rio City Council with 46,000 votes, a lone black woman in the sea of white, male, wealthy politicians. They also silenced the voice of a spokesperson for minorities, for the LGBT community, for the dignity of favela dwellers, for women in general, for the human rights of all Rio’s citizens, including the right of young black men not to be shot dead as suspects by violent, gun-happy policemen, especially those of the 41st Battalion, the most lethal in Rio.

Growing up in the favela of Maré, Marielle had everything stacked against her, because the destiny of most poor black women in Brazil is still the lowest paid manual jobs, maids, cleaners, nursemaids. Research has shown that only a tiny percentage of children from the poorest homes, whose schools are usually the worst, will break through the ceiling of poverty and go on to have a career, to be successful. But Marielle got herself a degree and an M.A. and became a model for favela children, especially girls, an example of what could be achieved.

https://www.facebook.com/ali.rocha/videos/10156458271800992/

Marielle speaking at a protest meeting for a woman’s right to abortion, December 2016. Video: Ali Rocha

So was Marielle killed because she had successfully bucked the system? Because she believed in equality, justice and human rights?

Killed by the militias

A week after her murder, the police have questioned scores of people, have scanned hours of CCTV footage showing the two cars which followed her, have traced the bullets that killed not only Marielle but her driver Anderson Gomes, but seem no nearer to finding the killers.

For experts who study crime and security in Rio, though, there is little doubt that she was killed by the militias, the gangs of off-duty or ex-policemen who now constitute a parallel power in the city. Sometimes the militias work hand in glove with the organised crime gangs who control drug and arms trafficking and lorry hijacking, sometimes they compete with them for control of a particular area. But together this parallel power structure has more manpower, more arms, more funds and more control over large swathes of Rio and its suburbs than the police forces, including the federal intervention force sent there in February.

For hundreds of thousands of cariocas, it is the militias who, by taking their cut, control their utilities, services like gas, water, internet; it is the militias who decide which bars or shops, by paying for protection, can operate without being broken into and robbed; and during elections, it is the militias who decide which candidates can campaign in their areas, paying for access, and even who the population should vote for, through micro-control of voters. Anyone who tries to resist the authority of the militias is simply eliminated, killed.

A pole of resistance

But Marielle was independent, she had her own agenda, and she belonged to PSOL, a socialist party uninvolved in the massive corruption schemes which have engulfed Rio in recent years. She was a pole of resistance to the militias, she represented an alternative to a population trapped between the world of the criminal powers and the world of official, often corrupt and violent police power. Marielle said that when she took her degree, she was one of only 1% of the Maré population who had access to a university, but now ‘about 10% are going to university, thanks to community preparation courses organised by civil society, not because of public policies’. In election year, she would have played an important role in raising issues, in denouncing discrimination and injustice. Is this why she was killed?

In today’s Brazil anyone who dares to raise their head above the parapet runs the risk of being killed. Community leaders and indigenous leaders in the Amazon, landless workers’ leaders all over the country, union leaders and environmentalists are murdered on an almost daily basis for defending their land, their homes, their forest, their rivers.

Then women are killed every day for being women. Children are killed in crossfire in shantytowns. Young black men are shot every day, for the crime of living in gang or militia-dominated favelas. Last year in Brazil over 60,000 people were murdered. There is a permanent, undeclared civil war being waged in Brazil. The government ordered intervention in Rio because middle class areas were being affected, President Michel Temer, thought he could score a quick public relations triumph sending in the army.

For most analysts, the Rio intervention, an unplanned, underfunded operation will achieve nothing. Instead it risks exposing soldiers to contact with drug gangs, and consequently to a Mexican- style contamination of the armed forces.

Painting the façades

As Rio has been taken over by parallel, criminal, power systems, the authorities seem unable to comprehend what is happening. None more so than the city mayor, Marcelo Crivella, who announced after a flying visit to Rocinha, Rio’s biggest favela, that he would have the road-facing houses painted bright colours, to hide their ugliness, so that people driving along the road can look up and see a pretty, organised community of working people.

Those who defend real solutions for Rio, not just a coat of paint, however, say that what is needed is massive investment in social infrastructure for the favelas and poor communities to make up for the years of neglect. Instead of abandoning them, allowing the militias and drug gangs to move into a power vacuum, governments need to show presence – a positive presence through schools, health posts and jobs, not just a negative presence through police raids and shootouts. Marielle should no longer be an exception, one who got away, but the rule.

Her brutal death sparked off a huge wave of indignation, revolt, and anger all over Brazil, and in other countries. In death she has become famous. The question is will this indignation continue? Will Marielle still be ‘presente’ during the election campaign with her message of tolerance and solidarity? Will the thousands who have protested her murder be enough to drown out the messages of hatred and intolerance coming from some of the candidates? Will the thousands who live under the yoke of the militias and the drug gangs defy them and demand an end to their control? Will other Marielles emerge to lead them?