This article was first published by History Workshop on 12 May 2021. You can read the original here

This spring marks the 45th anniversary of the military coup that ushered in the most violent years of Argentina’s history. Contemporary social movements struggling to uncover the full dimensions of those asphyxiating years have turned March 24th into a popular memorialising event. Usually, hundreds of thousands are drawn onto the streets – although in 2020, as Covid-19 began to impact the country and the government imposed a strict lockdown, activists were limited to hanging symbols outside their homes. This included the hanging of pañuelos; the emblematic neckerchief associated with the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo who mobilised to demand the return of their missing children. This year, human rights groups planted 30,000 trees in memory of the victims of forced disappearance. While the memorialising of these years takes place across Argentina, Argentinian terror extended beyond national territory. This has implications for histories of the global Cold War; it reveals the expansive logic of state terror in Latin America and the ways in which ideological violence and terror reached across borders and over continents.

Conventionally referred to as the ‘Dirty War’ or ‘state terrorism’, this period is sometimes understood as a specifically Argentine phenomenon. And there are good reasons for this: unique features distinguish the junta from contemporaneous regimes in the region. In contrast to its neighbour Chile, ruled by the iron fist of General Pinochet, Argentina was administered by the chiefs of the three wings of the armed forces (the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force), each one vying for dominance. Whereas in Pinochet’s early years, thousands of leftists were rounded up and publicly tortured in the national stadium, state terror in Argentina was waged in a deliberately concocted climate of confusion: people disappeared in the night and the fog.

Unlike other repressive Latin American states, including Pinochet’s Chile, the CIA was not directly involved in overthrowing the elected government in Argentina. Nevertheless, discretion and speed in carrying out countersubversive repression was encouraged by the US government under President Gerald Ford. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger advised his counterpart in Argentina, Admiral César Augusto Guzzetti, a from the navy and proponent of neo-Nazi germ theory, on how to avoid the ire of the international media faced by Pinochet. Kissinger advised Guzzetti: ‘if there are things that have to be done, you should do them quickly’.

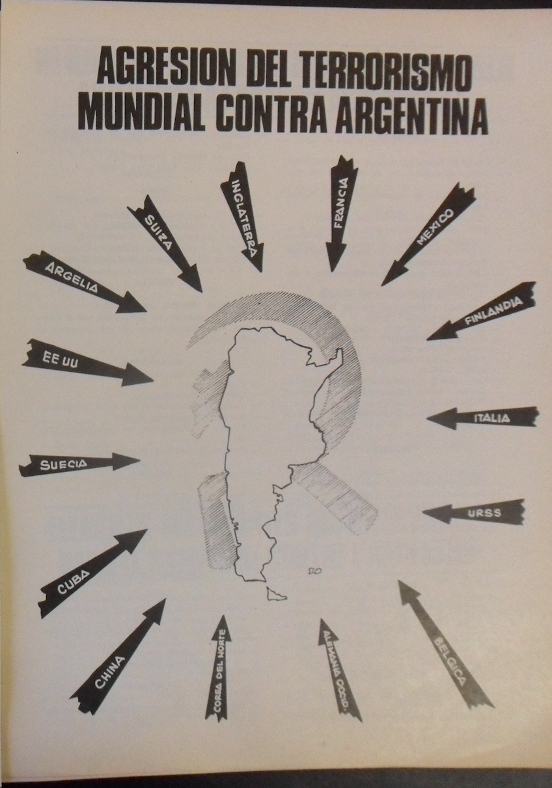

While there may have been unique characteristics of Argentina’s dictatorship, the terrain on which the campaign of terror was waged was certainly not – as scholars are increasingly demonstrating – confined to national territory. This is significant and should be of interest to global historians, as it helps to uncover the porous borders of state violence against internal enemies. Histories of state policing of protests and opponents, for instance, primarily focus on operations within national borders. Nevertheless, there is a distinct history to be told of states operating abroad against domestic opponents.

There are fairly well-known and evident instances in which the national dictatorship coalesced with international dynamics. New research has emphasised both global resistance as well as the globality of Argentine state terror. For example, while the junta attempted to exploit the 1978 World Cup held in Argentina to improve its international standing, the event was also used by exiles and human rights campaigners across the world to cast a critical eye on the situation in the country. A few years later, a regime weakened by an ailing economy, growing opposition and internal divisions mounted a botched invasion to recover the Malvinas/Falklands from Britain, with the resulting humiliation mortally wounding its ability to cling to power.

But the mixture of secrecy and violence that characterised the regime’s domestic actions was also a feature of its global activities, as shown by Plan Cóndor. This was a covert programme of collaboration and information sharing between the intelligence services of six Latin American countries. A more comprehensive picture of the Plan is being reconstructed by researchers through oral histories and the discovery of new archives. These have revealed that task forces could track down, kidnap, torture, and murder so-called ‘subversives’ in neighbouring countries.

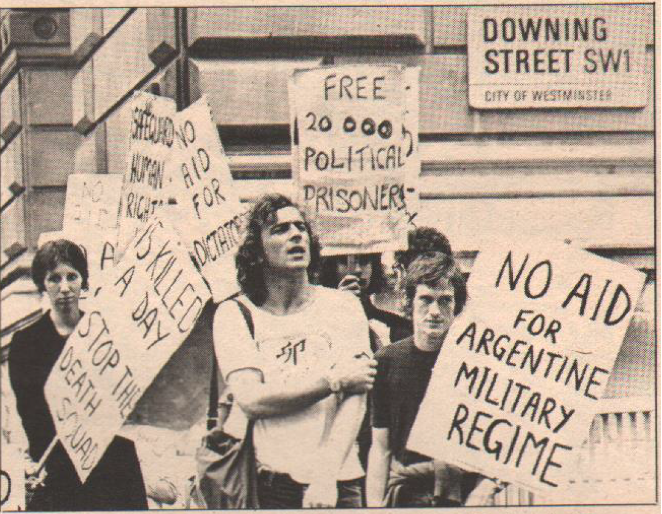

Less has been discussed about how the tentacles of the Argentine armed forces reached as far as Europe, in a war of intimidation against exiles, solidarity groups, critical politicians, and human rights campaigners. My research into UK-based solidarity networks led to a discovery. One of my oral history interviewee’s personal archives contains a press release circulated by an Argentina solidarity organisation. This revealed a largely forgotten story worth dwelling on:

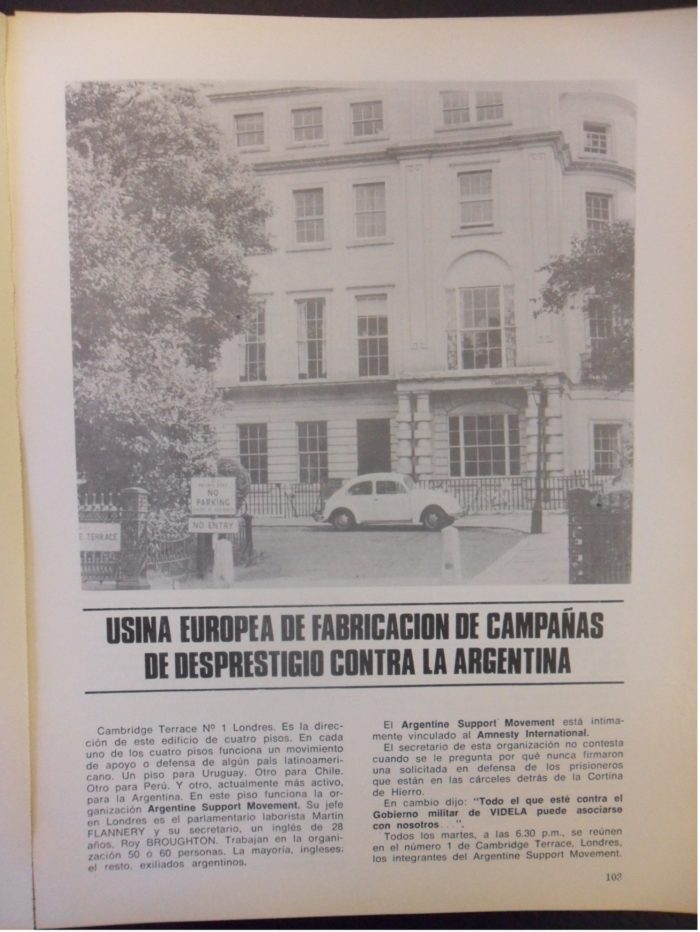

In July 1977, a man going by the name of Hugo Mario Sofia appeared at 1 Cambridge Terrace in London, a property on the edge of a Regency-era row of terraced mansions, moments from Regent’s Park. The building was run by the Catholic Institute for International Relations which allowed a variety of human rights and Latin American organisations to use its four floors as office space. Claiming to be an engineer from the Argentina National Shipping Company, Sofia spoke to the secretary of an Argentina solidarity organisation and proceeded to ask searching questions about the group’s membership and activities.

During this conversation, an Argentine activist who cannot be named, walked into the room. She had been imprisoned in the Naval School of Mechanics, a notorious secret detention camp in Buenos Aires, and managed to escape and find refuge in London. She immediately recognised Sofia as her former interrogator, who had brutally tortured her only months earlier. According to the accounts, the man stared menacingly back, clearly recognising her but unperturbed by the situation. She immediately left the room, no doubt horrified by seeing his face: not only would the trauma of her detention follow her around; so would her actual torturer.

The story went under the radar of the British media, but was nevertheless picked up by Lord Avebury, a peer in the Liberal Party with ties to human rights organisation Amnesty International, who demanded the government investigate, find Sofia and consider his deportation. As far as we know, Sofia was not seen again in London. But a dictatorship propaganda text from September 1978 featured in its pages a photo of 1 Cambridge Terrace. This trilingual publication (in Spanish, English and French), titled Argentina and its Human Rights was circulated internationally to combat global opposition, and described the building in London as a ‘factory’ for discrediting Argentina.

The anecdote of Sofia’s visit and the propaganda against solidarity groups speaks to the willingness of the Argentine regime to expand its practice of state terror beyond its borders. Other violent events suggest it could have been worse: Orlando Letelier, a charismatic Chilean diplomat in exile, had only months earlier been murdered in Washington D.C. by General Pinochet’s spies, while similar fates befell lower profile Argentines in places like Peru and Mexico.

We know from a May 1977 CIA report that there were plans to dispatch a team to London, disguised as businessmen, who would monitor solidarity activities. In this same document, it is claimed that Condor leaders even contemplated assassinating people living in Europe deemed to be a terrorist threat, including Amnesty International figures. Meanwhile, those who sought to extend the violence in the Argentine armed forces believed that a Third World War was underway. They also promoted anti-Semitic notions that a global Zionist conspiracy threatened Argentina. The implication was that the terrain of conflict was international.

Countries of refuge were thus not merely distant places away from the intense state repression of the Southern Cone dictatorships; they also occasionally became sites of contestation, conflict, and even danger themselves. Exiles, alongside local allies, not only sought to mount resistance to their home governments, but dictatorial states directly interacted with, intimidated or even killed their national opponents abroad. Stories such as these present a challenge for the conventional divide between the domestic and international spheres, demonstrating the need for a more interconnected and global perspective of Latin American state terror.

Main image: gallery of photos of the mothers and fathers of children stolen by the military regime and for whom the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo have been searching since 1977.

Dr Pablo Bradbury teaches History at the University of Liverpool, and International Relations at the University of Greenwich International College. His PhD research looked at the Christian left in Argentina and its responses to the last dictatorship. Currently, he is investigating the global dynamics of and resistance to Argentine state terror. He tweets @PMBradbury.