Serena Chang reviews the new LAB publication, ‘The Past is an Imperfect Tense’ by Bernardo Kucinkski, translated by Tom Gatehouse. A book launch event hosted by Latin America Bureau and supported by Sounds and Colours, will be held online on 29 October 2020. This article was published by Sounds and Colours on 16 October. You can read the original here.

“What did we know about adoption? Nothing, absolutely nothing. Almost a lifetime later, when what had been done couldn’t be undone, I decided to study the issue. Today I do know something about it, though not a great deal. A handful of ideas fished from an ocean of problems.“

We are told, at the beginning of the The Past is an Imperfect Tense, that a father has sent his (unnamed) only son a letter banishing him from the family. We are told straight afterwards that the pain of sending this letter has affected the father deeply and that the boy’s mother didn’t identify with the letter’s content. In short, poignant chapters, the father then tells us the family’s story. The novel stacks up complex issues such as adoption and racial prejudice in a prose full of psychological reflections that are painful but fascinating to read.

I’m sure there will be a number of theories around why the boy is referred to as “the boy” throughout the novel, and it’s an interesting thought as to how that plays out in translation as well. My personal impression was that the father has attempted to sever himself from his son by not using his name, though still cannot help but think of the boy as somewhat infantilised and with complicated affection, as after all, the memories are there.

The fact of the boy’s adoption hangs over the story throughout, sometimes bubbling over and becoming the dominant theme. The father seems to constantly remind the reader of these circumstances. We understand that the couple adopt the boy through what is called “unofficial adoption”, or adoção à brasileira. It’s hard to find much research in English by way of information about this, and of course it’s a complicated issue. I notice that the choice of translated word “unofficial” is very important semantically. Later in the book, especially as the father feels more unease and strain, “illegal adoption” is sometimes used instead.

There are both memories of his son as a happy, playful child and descriptions of some of the early challenges faced by the family: as the boy was born with rickets, a condition affecting bone development, he needed corrective plaster casts for both his legs and he was poorly and helpless for parts of his early life. Some other difficult memories relate to visceral examples of how the boy (who is black but adopted by white parents) is treated with racial prejudice. The stories really speak for themselves, such as when he was waiting outside the doctor’s surgery for his mother:

“Two officers came out of nowhere, guns drawn. They forced him to stand spread-eagled while they searched him, his hands on the roof of the car.”

We glimpse some of the father’s professional work interspersed amongst his personal accounts. As a documentary producer, his work covers some fascinating sociopolitical themes; including the Palestinian diaspora in Brazil, the Sandinista Revolution (overthrowing the dictator Somoza) in Nicaragua and the Cabanagem rebellion. As well as being informative, I found these snippets reinforced some of the background context to the novel’s characters and explored some complex issues. Revolution and immigration particularly stand out; the boy is adopted during the darkest years of Brazil’s military dictatorship, the father discusses how his grandfather was a Lebanese immigrant while his wife is the daughter of Bessarabian Jews. We are reminded that what seem like deeply personal circumstances are not formed in a vacuum, but that families everywhere are coloured by the state of the world they live in.

Drug addiction takes over the family’s story during the boy’s adolescence, leading his father to question his actions. The narrative contains increasingly more ruminations on part of the father, snippets of research, quotes from scientists and doctors. The questioning, itself heart-wrenching to read, and the father’s attitude shows how hindsight is a double-edged sword, freshly sharpened here with some dangerous emotions. Though we know he has sent a difficult letter to his son, he punishes himself so heavily too: perhaps in a way only a parent can.

It feels often like a novel where optimism is hard to come by, but the sketches of personal relationships with both family and friends give the novel its underpinning poignant tone. This delicate balance, together with such difficult subject matter addressed so succinctly, shows fantastic skill both on part of the original writing and translation into English by Tom Gatehouse.

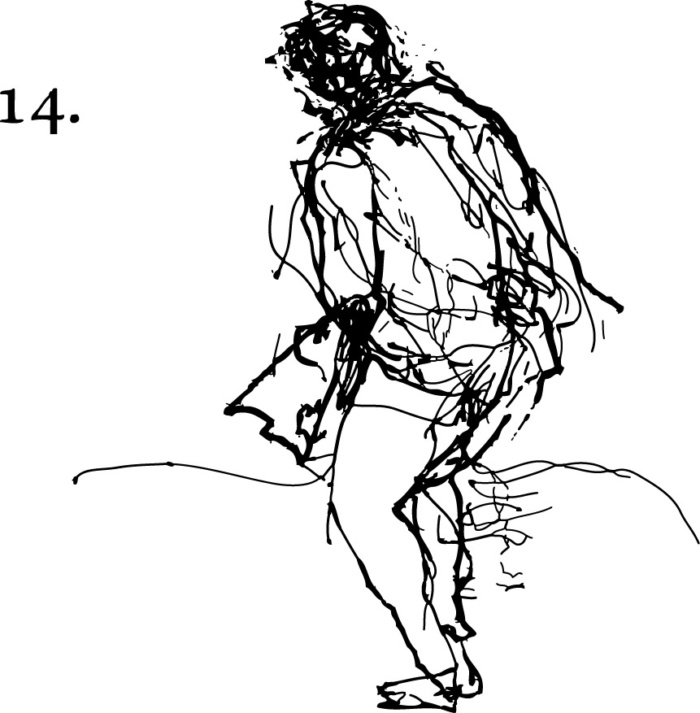

I’d also like to round off by saying that the illustrations by Ênio Squeff are an exquisite touch. Each to their own, but I admit that when I finished my first read, I had a leisurely glass of wine, put ‘Father and Son’ by Cat Stevens into my headphones, and page-turned every drawing. I challenge anyone to do the same without crying.

Bernardo Kucinski is a Brazilian journalist and political scientist. He has received Brazil’s Jabuti Award on two occasions and was awarded the Brazilian National Library Literary Price in 2014. The Past is an Imperfect Tense and his previous novel K are both published by the Latin American Bureau in partnership with Practical Action Publishing.