Mapuche – the ‘terrorist threat’ in Chile

by David Dudenhoefer*

As Chile recovers from the 7.8-magnitude earthquake that fractured the country’s south-central region in late February, the administration of President Sebastian Piñera – who took office two weeks after the quake – would seem to be headed toward a convulsive relationship with that region’s native Mapuche.

Piñera inherited a simmering conflict with the Mapuche – Chile’s largest indigenous ethnicity, constituting about five percent of the national population – from the centre-left Concertación coalition that governed the country for the past 20 years. In their struggle to recuperate lost land and halt projects that threaten the environment, Mapuche communities and organizations have occupied land, blocked roads and staged other protests, whereas radicals have hijacked and burned logging trucks and set fire to tree plantations. Concertación administrations responded to that unrest with repressive policies that contradicted their democratic and socialist principles.

Criminalising protest

“The state’s reaction has been to criminalize Mapuche protest,” said José Aylwin, co-director of the human rights organization Observatorio Ciudadano, which monitors the conflict and provides free legal aid to Mapuche defendants.

During the past decade, at least a thousand Mapuche have been arrested, imprisoned tribal leaders have staged hunger strikes, and police have injured hundreds of, and killed three indigenous protesters. The early indication is that Piñera – the country’s first president from the right in two decades and a law-and-order candidate – intends to maintain, if not strengthen, that authoritarian approach. And as Chile prepares to celebrate the bicentennial of its independence from Spain this year, Mapuche activists have promised to intensify their resistance.

In the first major protest following the quake, approximately 200 members of the Mapuche Territorial Alliance gathered in the southern city of Temuco on April 23 to demand that the government resume negotiations for the purchase of approximately 24,000 acres of land claimed by their communities. The protesters warned that they would occupy some of the disputed properties in one month if the administration hadn’t restarted negotiations, which were abandoned before Piñera took office.

CONADI to be restructured

Following the protest, the director of the government’s National Indigenous Development Corporation (CONADI), Francisco Painepán, told the local press that the administration would continue the policy of purchasing land for Mapuche communities, but its first priority was to help the communities that suffered the most earthquake damage. Two weeks later, however, Piñera announced plans to restructure CONADI in order to make it more efficient and prevent the corruption that has been associated with land purchases. He also announced that CONADI would dedicate more of its resources to urban populations, since an estimated 70 percent of the country’s Indians now live in cities.

The announcement drew fire from activists who pointed out that rural Mapuche suffer twice the national poverty rate, which is why so many have moved to cities. Studies have shown that many Mapuche families lack enough farmland to support themselves.

Human rights lawyer Juan Jorge Faundes, who directs the Fundación Instituto Indígena for the bishopry of Temuco, called Piñera’s offer to improve CONADI’s administration good news, since the institution’s slow and inefficient response to Mapuche demands has exacerbated past conflicts. However, he said the government should not scale back the purchase of ancestral lands for Mapuche communities.

Faundes explained that the administration of President Michelle Bachelet, who left office in March, approved 115 requests from Mapuche communities for the restitution of ancestral lands. However, her administration only managed to purchase 60 percent of that land before leaving office. The government has refused to expropriate land for indigenous communities and some landowners have demanded exorbitant prices. Faundes added that another 308 Mapuche communities have presented requests for land that CONADI has yet to respond to.

“The current government can’t ignore the historic debt,” he said. “Returning the requested land is an obligation of the state.”

Piñera has made no mention of the Mapuche Territorial Alliance’s demands, nor the restitution of Mapuche lands. However, the chief of police for the Novena Zona, in south-central Chile, recently told a local radio station that his troops were prepared for a Mapuche mobilization.

“It is quite possible that there will be a lot of conflict under this administration,” observed Aylwin.

History of attrition

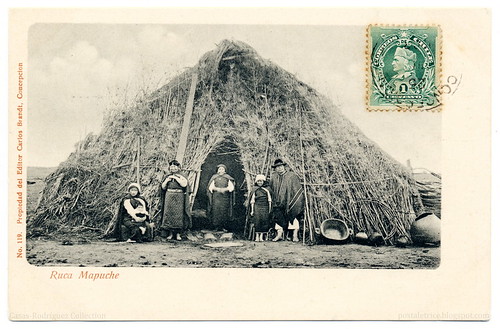

Mapuche means “people of the land” in their language, Mapudungun, and their territory once stretched from the Pacific coast and  islands of Chile across the Andes into Argentina. They defended that land from the Incan and Spanish empires, but in the 1880s the Chilean and Argentine armies defeated the Mapuche. Faundes explained that following their subjugation, the Chilean state granted Mapuche communities “mercy titles” that totalled 1.2 million acres – about one tenth of their former territory. However, the Mapuche lost half of that land during the 20th century as a result of laws to divide communal land, the sale of individual properties and a significant amount of swindling. Land restitution has thus far been limited to areas covered by the mercy titles that communities lost ownership of, but some groups are pushing for the return of territory that Chile took from the Mapuche during the conquest.

islands of Chile across the Andes into Argentina. They defended that land from the Incan and Spanish empires, but in the 1880s the Chilean and Argentine armies defeated the Mapuche. Faundes explained that following their subjugation, the Chilean state granted Mapuche communities “mercy titles” that totalled 1.2 million acres – about one tenth of their former territory. However, the Mapuche lost half of that land during the 20th century as a result of laws to divide communal land, the sale of individual properties and a significant amount of swindling. Land restitution has thus far been limited to areas covered by the mercy titles that communities lost ownership of, but some groups are pushing for the return of territory that Chile took from the Mapuche during the conquest.

The Mapuche began demanding the return of their ancestral land following the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, who ruled Chile with an iron fist from 1973 to 1990 and who mandated the division of their communal land. They’ve also fought projects that threatened the region’s natural resources, such as new roads and dams.

Mapuche territory has been transformed during the past three decades, when most of the region’s forests were cut and replaced by exotic pine and eucalyptus plantations to supply pulp, paper and wood product industries. Between them, Chile’s two biggest forestry companies – Forestal Arauco and Forestal Mininco – own approximately 1.7 million hectares (4.2 million acres): more than four times as much land as the Mapuche. Those companies have consequently become the target of sabotage by radical groups such as the Arauco Malleco Coordinating Committee, and some of their properties have been taken over by Mapuche communities.

“Spiral of violence”

Faundes said Concertación administrations were initially slow to respond to Mapuche demands, but when communities began occupying farms and radicals burned logging trucks and tree plantations, the government responded by prosecuting Mapuche activists with an anti-terrorist law that was drafted by the Pinochet regime, and which allows testimony by anonymous, masked witnesses. The law was complemented by harsh police tactics, which resulted in what Faundes called a “spiral of violence.”

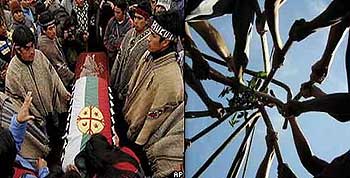

Last August, 24-year-old Mapuche protester Jaime Mendoza was fatally shot by police during an operation to evict people from occupied land. In January of 2008, 22-year-old Mapuche activist Matias Catrileo was killed under similar circumstances. In January of this year, a military tribunal found police officer Walter Ramirez guilty of fatally shooting Catrileo in the back and sentenced him to two years of probation.

Last August, 24-year-old Mapuche protester Jaime Mendoza was fatally shot by police during an operation to evict people from occupied land. In January of 2008, 22-year-old Mapuche activist Matias Catrileo was killed under similar circumstances. In January of this year, a military tribunal found police officer Walter Ramirez guilty of fatally shooting Catrileo in the back and sentenced him to two years of probation.

Human rights organizations have criticized the Chilean government for permitting police brutality and for using the anti-terrorist law, which is below international standards. Mapuche groups have filed cases against the government with the Inter-American Court and have requested that UNICEF investigate violence against minors, such as an incident last October when seven children where injured by rubber bullets during a police raid on their school.

“During the dictatorship, the repression was more generalized. Under the democratic governments, repression has been focused on the Mapuche,” said Mapuche activist Gabriela Cafucoy. She claimed that many jailed Mapuche leaders were falsely accused and convicted based on the testimony of masked witnesses.

Cafucoy cited the example of Juana Calfunao, the lonko (chief) of the community of Juan Paillelef, who has been arrested and jailed on various charges and is currently serving a six-year sentence for the crime of “resisting authority”. She also mentioned Pascual Pichún, the lonko of Temulemu, who was one of the first people charged under the anti-terrorist law since the country’s return to democracy.

One family’s struggle

Pascual Pichún is all too familiar with the Chilean government’s dichotomy of democracy and repression. For more than a decade, he and his neighbours in Temulemu – a village of approximately 250 people 30 miles north of the Temuco – have struggled to recuperate their ancestral land. Last year, the government finally purchased the property that they have occupied for years, though they have yet to receive the title for it. The purchase represents a major victory for the people of Temulemu, but it is one that Pichún and his family have paid dearly for.

Pichún and two of his sons have been arrested and accused of various crimes, all of which he claims they are innocent. He said their arrests were in reprisal for his role as a leader of the Temulemu land occupation. Pichún spent five years in prison for the crime of “terrorist threat” based on the accusations of masked witnesses that he believes were paid to testify against him. His son Rafael also served five years for the crime of burning a logging truck, whereas his youngest son, Pascual, fled the country to avoid standing trail for the same crime.

“They used to say we (Mapuche) were lazy and drunks, but now they call us terrorists,” he observed.

Pichún spoke in front of a small wooden house with a metal roof that he shares with his wife, children and grandchildren. His wife, María Coñonao, explained that the last time he was arrested, a busload of police officers arrived at their farm, broke down their door, and pointed guns at the entire family, including her two-year-old grandson.

Coñonao lamented that her youngest son, Pascual, who returned from seven years of exile in Argentina earlier this year, was arrested on the day of earthquake. He is currently in jail awaiting trail on charges of burning a logging truck with his brother in 2002.

“We have suffered very much,” Coñonao said. “I hope we are finally winning our struggle.”

Pichún explained that his current priorities are getting his son out of jail and working with his community to determine the a long-term plan for managing the land the government has purchased for them. He said that in spite of the police repression, the repeated arrests and the years he spent in prison, he never considered abandoning his fight to recuperate that land.

“They can’t stop me, because behind me, there are a lot of people,” he said. “The poverty here obliges us to fight.”

Future battles

Pichún said he plans to collaborate with the Mapuche Territorial Alliance, which was founded last year to coordinate support among communities. Mapuche clans are quite independent and many Mapuche identify more with Chilean society than their ethnic group, so there is hardly a united Mapuche movement. There are no indigenous members of congress, and Gustavo Quilaqueo, who founded the first Mapuche political party, Walimapuwen, didn’t get sufficient signatures to run as a candidate for congress in last year’s elections.

In 2008, Chile became a signatory of the International Labour Organisation’s Convention 169, which mandates that indigenous people be consulted about laws and projects that will affect them, but Faundes said the government has hardly begun to comply with it. Piñera’s decision to reorganize CONADI without consulting indigenous leaders is a perfect example of the general disregard of the agreement, though it could eventually facilitate peaceful conflict resolution. However, given the current state of tension, the radicalization of some Mapuche groups, and the government’s reliance on brute force, that eventuality remains a distant one.

Law and order were central to Piñera’s campaign platform, which makes many assume he will give the police a free hand against the Mapuche, but anyone who believes their resistance can be crushed is ignoring the conflict’s trajectory. Despite hundreds of arrests and more than 70 Mapuche prisoners, their movement is stronger than ever. The ineffectiveness of the current strategy was recently illustrated by the district attorney in one of main conflict areas, who told reporters that there had been a 324% increase in crimes by Mapuche radicals between 2008 and 2009.

Advocates of the hard line approach to the Mapuche conflict should pay attention to such statistics and consider the cases of leaders such as Pascual Pichún, who despite repeated arrests and half a decade in jail, remains committed to his cause.

“I will continue to struggle so that my people can have a dignified life,” he said.

* David Dudenhoefer is a freelance journalist based in Peru who covers much of South America.This article was first published in OpenDemocracy.