In 2017, Brazilian authorities decided to ban paraquat because of its links to Parkinson’s disease. But since then, imports have increased, and restrictions have been relaxed due to pressure from foreign chemical companies.

Translated by Tom Gatehouse. You can read the original (in Portuguese) here. This is the second in a series of articles written and published in Portuguese by Agência Pública, São Paulo and translated and published in English by LAB.

‘First he had fever and irritated skin. Then cold sweats, diarrhoea, and low blood pressure. We rushed him to hospital. His skin was all burnt and started coming off his body. I can hardly bear to remember it,’ says an emotional José Quintino, a dairy farmer.

He is speaking of his son Júlio, who died in 2016, aged just 22, in Cascavel in the state of Paraná. ‘Doctors came from all over, but there was nothing they could do. Gradually, he stopped breathing. They said that his lungs had been completely burnt out.’

Cause of death was confirmed as respiratory failure brought on by acute poisoning, following exposure to agrotoxins.

‘Paraquat destroyed his lungs. It burnt his skin, his oral and nasal mucous membranes, eventually getting to his lung alveoli.

Lilimar Mori, epidemiologist

‘Paraquat destroyed his lungs. It burnt his skin, his oral and nasal mucous membranes, eventually getting to his lung alveoli. This agrotoxin has a desiccating effect; it desiccates and burns leaves. The same thing happens with skin, mucous membranes and lungs,’ says the epidemiologist Lilimar Mori, head of the Health Monitoring Division of the Paraná Department of Health and one of the doctors who confirmed the cause of Júlio’s death. He had been poisoned unloading soya hulls treated with the chemical.

And acute poisoning is not the only risk associated with paraquat. It also has links to diseases including Parkinson’s, as well as to genetic mutations and depression. In 2017, the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (Anvisa), linked to the Ministry of Health, decided to ban the chemical, which is used in pre-harvest crop desiccation. From September this year, a total ban will come into force.

However, Anvisa’s ruling did not impose targets for phasing out paraquat, exhausting stocks or importing it until the ban comes in, despite evidence of the risks. As a result, imports have only increased since it was banned, as Repórter Brasil and Agência Pública have learnt.

Offloading the risk

This lapse between the ruling and the ban coming into force has permitted a process known as ‘offloading’, as almost all the paraquat used in Brazil comes from countries where it has already been banned.

‘Ideally, once the decision has been taken to ban a product, it should be illegal to import it. As that’s not the case, companies end up ‘offloading’ it in Brazil, because normally what’s being banned is already illegal in their country of origin,’ says Luiz Cláudio Meirelles, a researcher at the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz) and a former coordinator general of toxicology at Anvisa.

This is true of the Swiss agrochemical giant Syngenta (recently acquired by ChemChina), one of the biggest paraquat producers in the world; the German company Helm do Brasil; and the Chinese companies Sinon do Brasil and Rainbow Defensivos.

In the UK (where Gramaxone, Syngenta’s brand of paraquat, is manufactured) and the European Union, paraquat has been banned since 2007.

Paraquat has been banned in Switzerland since the 1980s. In the UK (where Gramaxone, Syngenta’s brand of paraquat, is manufactured) and the European Union, paraquat has been banned since 2007. Even in China, where environmental regulation tends to be looser, it was banned four years ago. Nonetheless, paraquat manufactured in these countries continues to be exported, mostly to developing countries where legislation is more flexible, with Brazil being the main recipient.

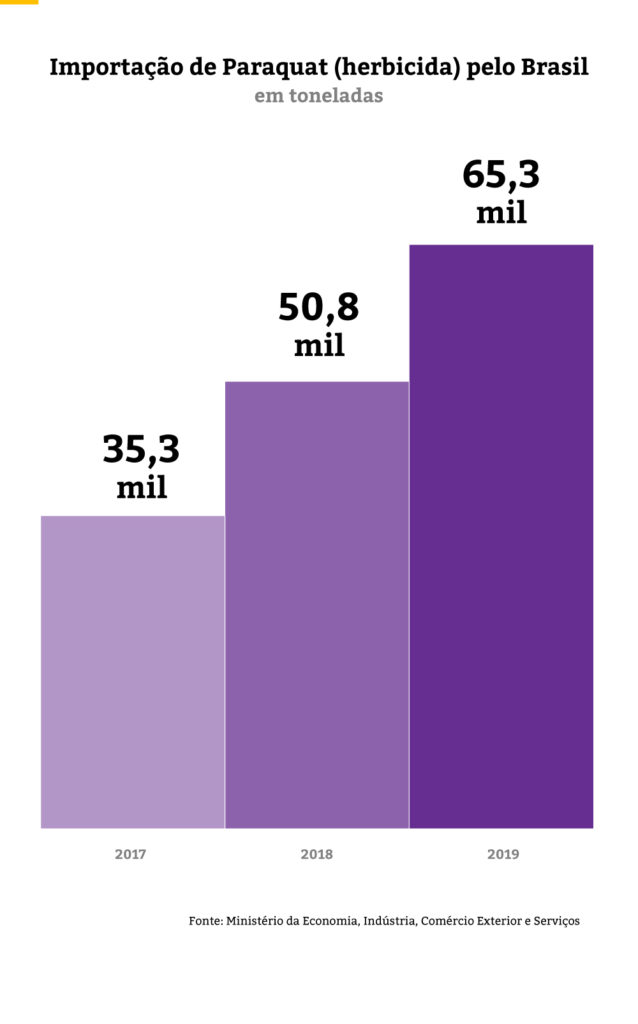

This phenomenon of ‘offloading’ is clear in data on imports from the Ministry of Industry, Foreign Trade and Services, available on the Comex Stat website. In 2017, when the decision was taken to ban paraquat, 35,300 tonnes of the herbicide were imported to Brazil. The following year, the figure increased to 50,800 tonnes and the trend continued upwards in 2019. By November last year, 65,300 tonnes of paraquat had been imported.

According to the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama), in 2017, paraquat was in eighth position in the ranking of the ten bestselling agrochemicals in Brazil, with more than 11,000 tonnes sold. In 2018, it had jumped to sixth, with more than 13,000 tonnes sold across the country.

A country no longer wants a product, so its companies need to offload their stocks.

Victor Manoel Pelaez Alvarez, economist

‘This attitude is typical; we’ve seen it before. A country no longer wants a product, so its companies need to offload their stocks. They take the opportunity to do so in countries that have set a transition period ahead of a complete ban,’ explains Victor Manoel Pelaez Alvarez, an economics professor and food engineer at the Universidade Federal do Paraná.

‘Evidence of the problems caused by paraquat has been piling up, and yet consumption has increased, even after the decision was taken to ban it. Imports should have stopped completely as of 2019,’ says the agricultural engineer Leonardo Melgarejo, vice-president of the Brazilian Acroecology Association for the southern region.

At the other end of this still-lucrative market for paraquat are rural producers. ‘As no limit was imposed on imports, they can stock the product until, for example, 2023, as there won’t be any monitoring,’ says Meirelles from Fiocruz. This means rural workers could be exposed to risks until 2023, or even later, until stocks run out.

See no evil

A spokesperson for Syngenta and ten other companies which sell paraquat in Brazil (the so-called ‘paraquat taskforce’) said that ‘supply and trade in products based on paraquat – like any other – is determined by the demands of farmers and the health of their crops’.

By email, Anvisa said that it sees no problem in the increase in paraquat sales during the transition, as ‘the ruling doesn’t impose targets for reduction or anticipate a negative trend during this three-year period.’

Originally, the Brazilian government did impose conditions on paraquat use for the three years prior to the complete ban in 2020. Among them, paraquat was to be banned for desiccation, which is its main use in Brazil. Anvisa argued it would help protect workers exposed to the herbicide.

However, just two months later Anvisa backed down under intense pressure from the agrochemicals sector. Five days after the first ruling was published, senior management from Syngenta in Brazil and Latin America held a meeting with Anvisa bosses. Anvisa’s public agenda shows that similar meetings took place throughout the following months, specifically to discuss the ban on paraquat.

the ‘paraquat taskforce’ is still working to try and get the ban overturned.

source from the agrochemicals sector

A taskforce of companies and associations of agricultural producers was created, and began lobbying Anvisa to revise its position, according to documents from the Ministry of Agriculture.

A source from the agrochemicals sector told Repórter Brasil and Agência Pública that the ‘paraquat taskforce’ is still working to try and get the ban overturned. ‘We’ve presented various studies and we’re looking at legal means of getting it done,’ they said.

This report is part of the project Por Trás do Alimento [Food Uncovered], a partnership between Agência Pública and Repórter Brasil to investigate the use of agrotoxins in Brazil.