“We dream of a green city, an inclusive city, full of squares, full of children. We dream of a fair, walkable, accessible, livable city. We believe in a greener, happier, more human city.” – Fundación Crecer

While cities are often the very core of social, cultural, economic and sometimes political life, they are increasingly detached from the natural and ecological systems in which they find themselves. Throughout Latin America, the pressures of economic growth and population increase place significant stress on the land and ecosystems interconnected with major urban spaces.

This is particularly complex in a region such as Latin America, home to a large portion of the world’s biodiversity. According to the World Conservation Union, Guatemala is number five on the list of Biodiversity Hot Spots in the world. The country’s architects and urban planners fear that losing endemic species to expansive and badly planned urbanisation could have worldwide implications.

Many voices of the chapter “Spaces of everyday resistance: the right to the city“ in LAB’s Voices of Latin America, advocate for the transformation of urban space – not only through redesigning physical infrastructure, but also by shifting people’s perspectives on how certain urban spaces can be used.

In an extended conversation with LAB, urban architect and executive director of Guatemala City’s Fundación Crecer for 12 years until March 2020, Ninotchka Matute further articulated this view. Matute stressed the need to shift the urban imaginary in her native Guatemala City, by reframing derelict spaces as those of potential, whilst upholding a responsibility of care for the environment.

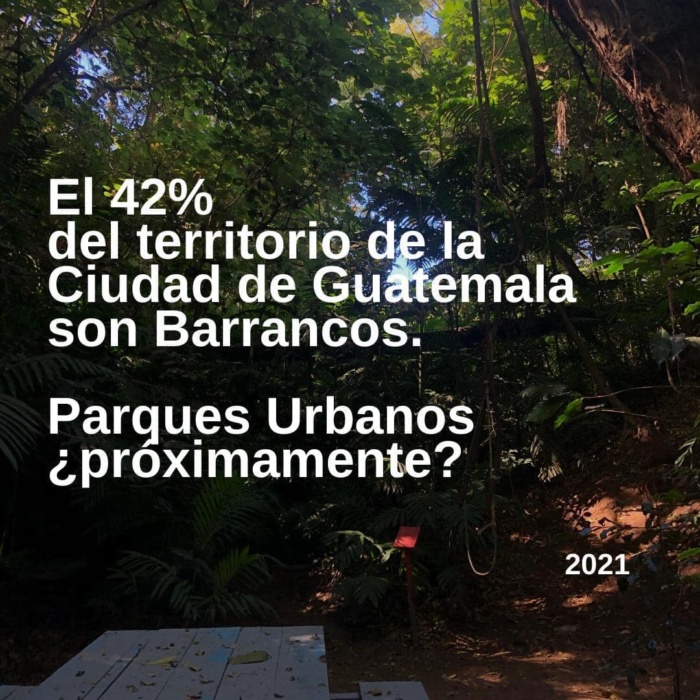

Ninotchka is an avid communicator on urban topics with a regular radio program, La Hora de Crecer and a website/blog, Hiperurbana. In her view, Guatemala City’s unique morphology presents a fascinating case study. Part of her work includes the reimagination of the city’s characteristic ‘barrancos’ – the natural ravines found throughout the urban area. Matute believes barrancos to be the protagonists in a story connecting urban development, societal issues and the natural ecosystems of the city.

City of Barrancos

Natural ravines known as barrancos make up about 42% of Guatemala City. They commonly hold negative connotations: they are seen as unsafe areas as they house vulnerable informal settlements; they are seen to pose a sanitary risk as they are often used as dumping grounds; they are seen to limit mobility and to divide the city because of their geographical formation.

“Unfortunately, barrancos are overlooked in the urban dynamic and they are at risk,” Matute explained to LAB. “Today, they are often perceived as residual (non-spaces) and for that reason they receive everything we don’t want to see: informal settlements, sewage, garbage.” But for Matute, shifting the perspective on how barrancos are currently perceived can have myriad impacts on Guatemala City and its inhabitants.

Barrancos, given their location around the city, have naturally put the brakes on uncontrolled and damaging urbanisation processes of the last decades, something to celebrate. What’s more, Matute argues that the distinct morphology of the barrancos offers a unique opportunity to reconnect urban processes to the natural sphere: “At the moment, they function more as dividers, but they would make great connectors with a proper design,” she told LAB. For example, they could be used to create “a circuit of bridges for cyclists and pedestrians”, presenting an alternative form of mobility in the city.

Matute further illuminates the enormous ecological potential of the ravines: “They are a natural reserve that produces a series of ecological services for the inhabitants of the city and its metropolitan area”. According to Matute, these water reserves are biological corridors and can act as lungs for the city.

As Matutue explains “Guatemala is among the top 20 countries with the most contaminated rivers. Our aquifer is increasingly being depleted. These are dramatic figures that make us angry, and so the environmental issue is an important axis for us that we can promote by the rehabilitation of the barancos as natural public spaces, ecological spaces, for people to enjoy as parks, and to connect the city.”

Matute strongly believes these spaces can be recovered and that decades of bad planning and urban development that has neglected the environment can be counteracted.

This begins by inverting the public notion of these areas and turning them into social and ecological “connectors” and understanding that they hold many ecological benefits. Shifting these vital ecological corridors into vibrant spaces that connect areas of the city, rather than divide, could significantly improve the urban fabric and the quality of life of its inhabitants.

Architectural attention

Matute’s Fundación Crecer in Guatemala City is a private non-profit organisation founded in 2007 with a strong conviction that the key to any urban process is its people. The team want Guatemala’s capital to be a diverse city full of dignified public spaces which generate opportunities for its inhabitants and contribute towards a high quality of life.

One of their focuses is on the potential to positively transform the barrancos of Guatemala City. But in order to carry out the work, it’s not just civilians’ perceptions that have to change, Fundación Crecer need the authorities to see their work and trust their vision.

As is the case in many cities across Latin America, relationships between institutions, local and central government are not always straightforward, and initiatives generated from outside of the municipality can be overlooked.

But naturally, with more attention on the barrancos and their possibilities for evolution, urban designers and architectural firms have begun to take an interest in converting them from negative spaces into vibrant urban areas. One of these projects, Barranco Invertido, came about in 2013 as a research proposal promoted by a collective led by Jorge Villatoro and Erick Mazariegos.

With Invers(Scapes), they used speculative design as a method to map a new urban imaginary and map new potentials for the barrancos. Then they set to sharing their ideas and working on public perception.

Barranqueando – La Jungla Urbana

Fundación Crecer has promoted and led the Mesa de Barranqueros collective, a series of environmental institutions and organisations with the shared objective of urban transformation through ecological sustainability. Crecer work collaboratively with them, organising different consciousness-raising activities, such as the Water Festival and the BioFest (Biodiversity Festival).

Fundación Crecer has also fostered citizen-led movements for revitalising the barrancos. As Matute explains, “It has been local inhabitants and NGOs who have taken the lead in the recovery of many ravines”.

With the help of Fundación Crecer, the citizens’ movement Barranqueando was formed in 2017, by a group of professionals (including the Barranco Invertido architects), visionaries, activists and urban youth dedicated to transforming the city into a green space and ensuring that care for the ravine ecosystems became part of the Guatemalan conscience. Their first project was to transform Jungla Urbana, the ravine section between zones 10 and 15 of the city.

‘The main objective of barranqueando is to convert barrancos into active urban territories without compromising their environmental qualities but by highlighting their nature, and identifying their productive potential, proposing practices and strategies for sustainable development that allow the integration of the barrancos into the city’s metabolism,’ their website states. On social media, the movement’s page promotes the use of this green community space through online talks, information packs, festivals and videos.

Fundacion Crecer also support Amigos de la Jungla Urbana (Friends of the Urban Jungle), a multidisciplinary network of people working in the Jungla Urbana section of ravine, now known as an ecological park, to support its transformation into a success story of integration, conservation and sustainability. The community promotes urban design initiatives that work in harmony with the natural environment, namely the plans to develop a cycleway through the ravines. They promote education about the ravines’ biodiversity and organise group activities to enrich the community and care for the ravine ecology, like gardening, litter-picking and eco-storytelling. They promote festivals within the space and even post style guides para barranquear!

Another citizen-led movement, but independent from Fundación Crecer, is Vicalama, named after a Maya Ixil term meaning “green and extensive valley.” A citizen-focused group, they foster the biodiversity of the ravines and promote them as rich and verdant urban landscapes and recreational areas, through education. Vicalama offer environmental education programmes, especially for children, teaching and spreading knowledge about reforestation, urban farming and organic composting. They teach in the urban farms themselves, in the city’s ravines.

The future of the barrancos

Since architectural collective Barranco Invertido began proposing the ravines’ potential for urban integration, and the Tactical Urbanism projects in green infrastructure followed, public perception has indeed been changing. This can be seen in the many barranco transformation initiatives that have been popping up and evolving over the last few years.

However, Ninotchka warns that “these proposals have not yet escalated enough to be transformed into forceful public policies; for the moment they are isolated citizen movements with the support of some environmental organisations.” There still haven’t been any successful proposals for cycle routes in the ravines.

While there has been progress on the idea of the ravines as potential eco-parks for the city, the initiative remains stalled. Interestingly, despite being outdoor spaces, the parks were one of the last public areas to receive authorisation to reopen during the pandemic closures. Now, following their reopening, they have effectively become safer alternative spaces for families to walk and exercise in outdoors.

For the initiatives to progress, awareness of the projects is key, as is international support. We can only hope that the ecological and social benefit of the ravines becomes more prominent and popular within the post-pandemic public imaginary.

For more on this topic, read Voices of Latin America.