This short video was produced by Circuito Gran Cine, a collective of film makers based in Venezuela that seeks to train young people from the Baruta neighbourhood of Caracas in video production. The young people receive workshops about human rights and documentary making, including directing, production, post-production and editing. The participants choose the themes they want to talk about and receive guidance from the collective’s experts.

The video is one of a series about the difficulties Venezuelans have faced during the Covid-19 pandemic, ranging from water shortages to the lack of internet for home-schooling. The episode above features journalists and human rights defenders who denounce the repression they experience and share information about the virus.

It is hard to understand the extent of the pandemic in Venezuela. Given the country’s complex humanitarian crisis, crippled healthcare system that often lacks basic medicines, the return of migrants from across the continent, poor housing and sanitation, it wouldn’t come as a surprise, if a tragic one, if Venezuela were suffering an acute crisis with the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic last March.

Yet we haven’t seen the staggering numbers of cases that have occurred in Mexico or Argentina, nor the horrifying scenes of bodies lying on the street witnessed in Guayaquil, Ecuador, or Manaus, Brazil. Had such scenes been occurring, it is hard to believe that news would not have been shared and amplified by foreign press, especially those hostile to the Venezuelan government.

Instead, the official figures relating to Covid-19 cases and deaths emerging from Venezuela have been surprisingly low. According to Johns Hopkins University, the total cumulative number of cases stood at 205,181 as of 8 May. Uruguay and Paraguay – widely seen as some of the countries who best handled the pandemic and who have far more robust health systems – both have more cases (216,146 and 294,233 respectively as of 8 May 2021).

Ex-minister of Health for Venezuela (1995) and president of the Centre for Development Studies, Carlos Walter, suggested that the real number of cases could be up to eight times higher than the official figure. The government has a monopoly on testing and does not release the data relating to the number of tests carried out daily, so it is hard to gauge an accurate estimate.

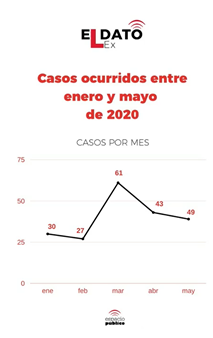

One unnamed witness suggested that on 18 April 2021, there was a queue of up to 130 for burials at a cemetery in eastern Caracas. Most of those to be buried were believed to have died due to Covid-19. The same day, however, the Venezuelan government reported only 17 Covid-19 related deaths. Part of the equation in keeping the figures low is the stifling of the press. When Coronavirus arrived in Venezuela in March 2020, attacks on the freedom of information more than doubled compared to the previous two months. Between 13 March and 13 May 2020, 22 journalists and other media workers were arrested.

Those arrested include Jesús Torres and Jesús Manuel Castillo, who were detained after publishing a video about suspected Covid-19 cases at a hospital in Los Teques, Miranda. They were both students of mass communication who also worked at Radio Cima. Beatriz Rodríguez, the director of the online daily, La Verdad de Vargas, was also arrested after the newspaper published an article about a ninth positive Covid-19 case in Catia La Mar.

Another was Darvinson Rojas, who features in Circuito Gran Cine’s video. He was arrested on 21 March last year after questioning the Government’s Covid-19 figures on Twitter. He explains in the video that he was simply doing his job: informing the population.

Gregoria Díaz, another journalist in the video, speaks about the persecution she faced after tweeting about a suspected Covid-19 case in February 2020. According to her Twitter and that of the National Union of Press Workers, she faced more harassment as recently as the 15 April of this year, after she published an article about the lack of beds for Covid-19 patients.

Many of the journalists arrested are charged with ‘inciting hatred’. The charge stems from the 2017 ‘Law Against Hate’ that originated in response to large scale protests against Nicolas Maduro’s government. The law is increasingly used by prosecutors against critics of the administration.

The law means that posting in spaces like social networks, which had previously been relatively ‘safe’, can now lead to arrests. Loyalists and government workers report to prosecutors posts on social media or text messages that do not agree with the official line. It is hardly high-tech tracking but is effective in silencing debate, if only temporarily.

Journalists in Venezuela are not alone in their battle for truth and information. The Maduro government has also repressed medical workers for speaking about the real numbers of COVID-19 in the country. Andrea Sayago, a bioanalyst at the Dr. Pedro Emilio Carrillo Hospital in Vela, Trujillo, was put under house arrest for ‘Misuse of Privileged Information’. She had warned colleagues about positive Covid-19 cases in the region via a Whatsapp Group.

The Ministries for Health and Science and Technology imposed limits on scientific investigation into the virus, including the requirement for any investigation to be registered with the Ministry for Science and Technology and approved by a committee of ethics. Rather than being a safety move, however, the requirements have been seen as a manoeuvre to discredit or even punish scientific researchers.

The truth surrounding the impact and management of the pandemic remains pushed in the shadows. Espacio Público, for example, claim that their request for information from the Ministry of Health for information regarding vaccination against Covid-19 was rejected. The request included questions about payment for the vaccines, their distribution, and the choice of the Sputnik V vaccine. The Health Ministry rejected the request on the grounds that the signatures ‘were not legible and there wasn’t an institutional stamp’. Neither are requisites for a public information request.

Repression of journalists and journalism is not new in Venezuela. The country has hovered at around the 148th position (out of 180 countries) in the Reporters without Borders Freedom of Information rankings for the past three years for which the rankings are available. Of Latin American countries, only Cuba and Honduras sit lower on the list.

In an interview with LAB for the Voices of Latin America project in 2018, Carlos Correa, the director of Espacio Público who features in the video, explained how the Venezuelan state had shut down alternative newspapers through controlling the supply of paper, and favouring outlets sympathetic to the government.

Nor is it likely that journalists will have an easier time of it any time soon. The trade union for Venezuelan journalists, El Sindicato de Prensa y Sociedad, continues to report the harassment of journalists. Just last month, three days before the re-arrest of Gregoria Diaz, Carlos Andrés Monsalve was also detained in the Dr. Gervasio Vera C hospital while visiting his sister. He believes his arrest was due to a tweet he made about the hospital conditions.

Fernando Fernández, a human rights defender, highlights in the video that ‘Freedom of expression is the best way to defend all rights, particularly the right to life’. Yhoger Contreras, a journalist from the Instituto de Prensa y Sociedad (IPYS) explains that information and the ability to challenge and verify that information is key to being able to make responsible decisions.

They would be correct during normal circumstances. But during a pandemic, the need for accurate information and a free, responsible press is even more important. It is vital that people understand the true extent of the impact of the virus in order to be able to keep themselves safe. Journalists play a key role in providing that information, stimulating democratic debate, and holding governments to account. With an accurate understanding of the virus and by recognising and accepting failures, we can learn to manage it better, to protect life, and hope to return to normality.

Francisco Elias Prada+Angela Rodriguez Torres/Ojos Ilegales+RED, the LAB partners involved in the Circuito Gran Cine project, produce powerful short films and photo collections that look at the issues facing economically deprived communities, where violence is the order of the day. They seek to fight for human rights by making the realities of those communities visible and by teaching those people the skills of cinematic production to be able to create their own discourse and fight the injustices they face. For more information about Circuito Gran Cine or Ojos Ilegales + Red, contact ojosilegales@gmail.com or fotoslibros.ilegales@gmail.com.