Organisations | 8 Tijax, Guatemala

As part of our ongoing collaborative Women Resisting Violence project in partnership between LAB and King’s College London, we are spotlighting Latin American grassroots campaigns and organisations that counter violence against women and girls. Read on to learn about 8 Tijax, who feature in our Women Resisting Violence podcast.

The collective 8 Tijax was formed in 2017 in Guatemala in response to a massacre at the Virgen de la Asunción children’s home just outside of Guatemala City. 8 Tijax is a group of volunteers who work with the families of victims and survivors and support their campaigns for justice in the courts.

The volunteers at 8 Tijax:

- Coordinate with lawyers to provide legal aid

- Arrange counselling and therapy for families and survivors

- Accompany families to court and cover transport costs

- Create media campaigns to dignify the memory and lives of the 56 victims

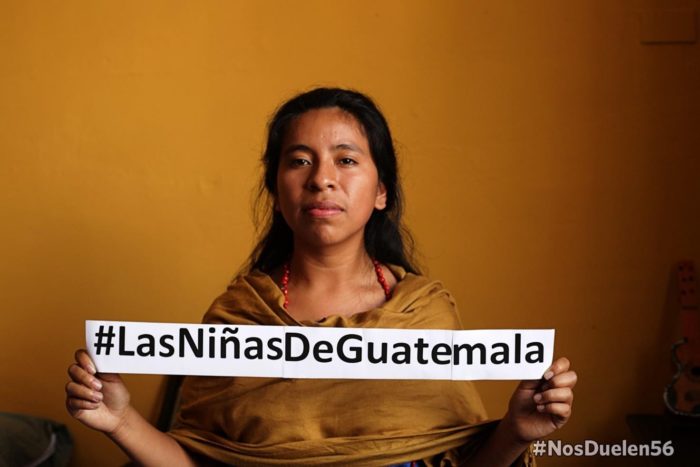

The collective is closely affiliated with the media campaign #NosDuelen56, which aims to preserve and dignify the memory of the 56 teenage victims of state neglect and abuse in the case of the Virgen de la Asunción children’s home, through collaborative cultural projects. NosDuelen56 is itself organised by the families of the victims, and focuses on demanding justice through the arts and journalism.

Read: Inside Ocho Tijax: Meet the Women in Guatemala Offering Support in the Face of Horror

State Violence against Girls in Guatemala

The Hogar Seguro de la Virgen de la Asunción in Guatemala was a state home for vulnerable and orphaned children, many of whom had escaped abuse, kidnapping or trafficking. Newspaper reports revealed that some of the girls’ parents had placed the girls in the home for protection from the mara street gangs and that the courts had taken other girls into custody because they’d been abused by family members, or because they were living on the streets.

These vulnerable girls were placed in the home for their protection, but in reality, they were mistreated. There were reports of physical and sexual abuse in the home and incidences of some children even being trafficked again. In 2013, cases of sexual abuse against the girls were brought to the courts and staff at the home were found guilty. In 2016, a family court declared that the punishment methods used by the school were paramount to torture and were in clear violation of the children’s human rights.

A newspaper report at the time gave further information about the conditions in the home — which was meant to accommodate five hundred residents, but in fact housed approximately eight hundred youths. There were separate areas for older girls, older boys, younger children, and those with disabilities and illnesses. The smallest area, called ‘Princesas’, was for pregnant girls waiting to be moved to another home, and for some of the smaller children who had been born in the home to adolescent girls —who may have been impregnated by the boys there, or by staff.

Parents who wanted to recover their daughters from the home were sometimes faced with a wall of bureaucracy or had to pay bribes for their children’s release.

March 2017 Tragedy

On 7 March 2017, girls and boys living in the home rioted and fled, to escape brutal conditions. They were pursued by the National Civil Police who found them and brought them back to the home. The 43 boys were taken to an auditorium, while the 56 girls were locked in a 7 x 6.8-metre classroom and left there.

Early in the morning of 8 March, a fire broke out in the classroom. Despite their cries for help, the girls were not released: 17 died inside the classroom, 24 died later in hospitals and 15 survived with severe burns, requiring facial reconfiguration and amputations.

In the days following the tragedy, the children remaining in the home were transferred alongside staff to other state or private homes, or were reintegrated with their families. A 2018 report by the UN found that this process was very irregular and there were cases where the children were exposed to unsafe living conditions and violence. The report also highlighted that the 15 surviving girls and the families of all the victims had numerous medical and psychological problems, as well as the need for protection. It highlighted the lack of answers: at this point, there were no outcomes from the criminal investigations, and no reparations.

Commenting on state officials’ attitudes towards these children, María Eugenia Villareal of ECPAT, an international NGO that tracks and fights the sexual abuse and trafficking of minors, who was involved in the case, said: ‘It doesn’t matter [to state officials] what the children endure, because they’re indigenous or extremely poor …This is why so many try to migrate to the United States. It’s because they’re fleeing the violence of the state, of their communities, of their families. Every type of violence is present here.’

8 Tijax is born

The 8 Tijax collective was formed the night of the massacre in 2017 at the Virgen de la Asunción Children’s home, as a group of friends: a graphic designer, a journalist, a sociologist, a dentist and a photographer watched the home go up in flames, with girls still inside, on their televisions. Feeling they had to act, they gathered and headed to the home to meet the families and accompany them to the hospital, or the morgue. They describe 8 Tijax as ‘a collective of love that is born in the midst of pain.’

Accompanying the families through the many medical and legal processes to follow, the group noticed an extreme lack of care on behalf of the Guatemalan government, who were neglecting to assist survivors and families and failing to seek justice by identifying and prosecuting perpetrators. 8 Tijax were already thinking of a long-term plan for support.

Still today, the group of volunteers work alongside the survivors and the families of the victims, supporting their campaigns for justice in the courts, organising counselling for the families, physical and emotional healing therapy and psychology sessions for the survivors and financial aid to cover transportation and other costs. They also create media campaigns to increase international attention and put pressure on the state.

Families demand justice: #NosDuelen56

8 Tijax are affiliated with the media campaign ‘Nos Duelen 56’, which is organised by the families of the victims and focuses on demanding justice through the arts and journalism. The campaign exists in order to preserve and dignify the memory of the 56 teenage victims, through collaborative cultural projects.

Soon after the fire, Nos Duelen 56 built a memorial in the Plaza de la Constitución, Guatemala City’s central square, where relatives of the deceased gathered every Friday to honour the girls’ memory and demand justice. In September 2019, the police removed the memorial, but it has since been replaced.

Another project Nos Duelen 56 carried out was to arrange for artists from all over the world to create portraits of the girls who died in the fire. In the campaign, 58 artists from Mexico, Italy, France, Spain, Argentina and Guatemala participated and publicised it in their own countries and a new call was made to involve more artists to join and create images to support the campaign #NosDuelen56.

One of the Guatemalan artists who participated was Sara Curruchich, an indigenous kaqchikel woman artist, composer and singer who stressed the importance of the quest for justice:

‘It’s important to shine a light on the ways in which history and justice in Guatemala have been covered up, like the history of people suffering. This is happening yet again with the femicide of young girls. From our spaces [as artists] we demand justice, and we want to speak out for the girls, the survivors, and those who died – who have left us with their strength to continue fighting for them.‘

Arising from this media campaign, the girls’ mothers set up their own group with the same name: Nos Duelen 56, to continue fighting against impunity for the perpetrators. And they are not alone: women’s organisations, human rights groups and lawyers, as well as international NGOs, have joined in solidarity to support the campaign for justice.

The crime committed against these girls highlighted the cruelty of the State and its involvement in torture, trafficking of minors, prostitution and other crimes, linked to government officials and extending as far as the Presidential office. Although the director of the home insisted that it was the police who’d been in possession of the key to the schoolroom door, he, alongside the Secretary and Sub-Secretary for Social Welfare and the National Civil Police officer in charge on the day of the fire, were detained alongside eight others. 12 public officials have been ordered to face public trial for charges of involuntary manslaughter, abuse of minors and breach of duty, but many say these charges don’t reflect the seriousness of what happened nor the consequences families and survivors are left to live with.

What’s more, the 15 survivors have also been accused of 19 different crimes including murder, grievous bodily harm, armed robbery, arson and public disorder; charges which would amount to 152 years in prison for the girls.

Future challenges

The movement for justice for the victims of the Hogar Seguro de la Virgen de la Asunción fire faces many challenges. The main hurdle is getting those responsible for the girls’ death to be held to account, when after four and a half years of court cases, the judgement process hasn’t even begun.

The judicial process has been littered with obstructions and delays and hearings have been continually postponed. Surviving relatives have faced mistreatment in court, such as being forbidden to cry in the courtroom; one of the survivors was forced to testify despite pleading not to; and the relatives were forbidden from entering the courtroom wearing t-shirts bearing photos of the victims.

Those involved in the campaign, including the girls’ families and their lawyers, have been intimidated and threatened. The 8 Tijax Collective have been intimidated, followed, and even received armed death threats .

Since the massacre, three relatives of the victims have been murdered – Gloria Pérez y Pérez, mother of Iris Yodenis León Pérez was killed in July 2018, alongside her 13 year old daughter Nury León Pérez. María Elizabeth Ramírez, mother of Wendy Vividor Ramírez, was killed in February 2021. Recently, Elsa Sequín, another mother who works with 8 Tijax and NosDuelen56, received death threats.

Despite these setbacks, the work of 8 Tijax and NosDuelen56 continues four years on from the massacre and is imperative in offering support to the survivors and remembering the victims of the tragedy.

Their work has contributed to a law being passed in August 2018 in the Guatemalan Congress, which provides the 15 survivors and their families with a monthly subsistence payment of US$654 for three years, and the equivalent of the minimum wage from the fourth year onward. Guatemala City’s main square has been renamed ‘The Girls’ Square’ and March 8 was officially declared ‘National Day for Victims of the Tragedy at the HSVA,’ a day of mourning and to demand justice.

As victims, their families and all of their supporters continue to demand justice and a proper investigation to find the truth of what happened that day, 8 Tijax remain their steadfast supporters.

Watch: NosDuelen56: Nadie las escuchó, aunque lo último que escuchó fueron sus gritos pidiendo ayuda.

Researcher: Ella Barnes

Main image: 8 Tijax / Facebook