Borderland Threads

Crafting narratives with Colombian migrant women in Antofagasta, Chile

ARPILLERAS

Borderland Threads weaves stories between countries and cultures. The 11 artists whose arpilleras and testimonies are presented here are Colombian women migrants living in Antofagasta. Through a series of intensive workshops over four months in 2022, they worked alongside a small team of academics and artists to produce these narrative artworks.

Click on an arpillera below to view it in full size and read the artist’s story.

Arpilleras

Testimonies

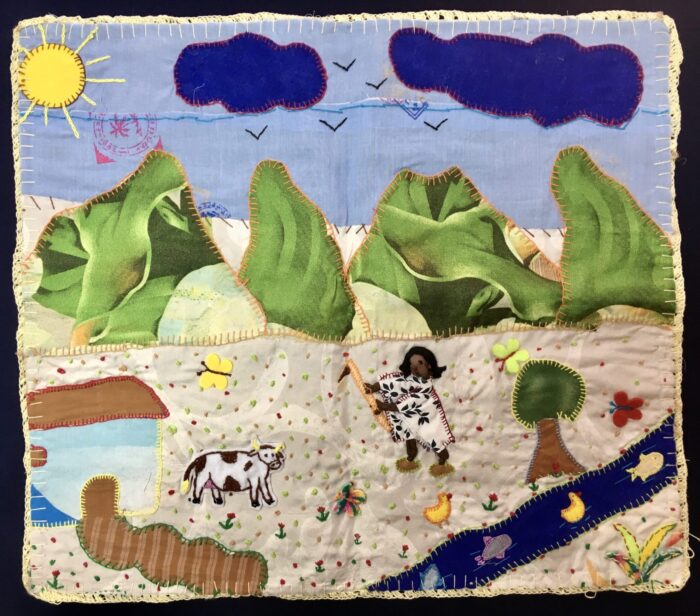

Arpillera by Claudia Rojas

Read Claudia's story below

My arpillera is about where I come from. We are from the countryside, from La Victoria, Valle de Cauca. There are mountains across from my house. We have a farm with cows. The Río Cauca flows through the nearby town. It’s a quiet town where the neighbours are friends and have known each other since childhood. We are very close. I find my town very beautiful.

My grandfather was a farmer, he had some land and he cultivated sugar cane, he also had a mill and made panela (unrefined sugar cane cubes). My mum was a housewife and I mostly spent time with her. I was always by her side.

I worked as a nanny and then met my husband and we had a little girl. We have a 16-year-old daughter. Her dream is to study at university. She already has clear ambitions. Over time, things became difficult in our town. My husband made the decision to come here to Chile. He said if we want to give our daughter a good life, an education, it wouldn’t be possible in our town. He came to Chile first and we didn’t see each other for four years. It was pretty hard.

My daughter and I have been in Chile for six months. At first, everything was so difficult. Where we live is a campamento, an informal settlement. When we arrived, there was a rubbish dump just below where we live. I felt really demoralised at first. Where I come from the houses are small, but they are pretty. We went from there to a campamento…

But my daughter has already been able to go to school. Here we are able to help her start studying for university. Coming here was a good decision despite the difficulties. And well, we just found out that I’m pregnant. With another baby, things will change again. But with God’s help, it will all be fine.

Mi arpillera es de donde yo vengo. Somos del campo, es un corregimiento del municipio de la Victoria Valle. Donde yo vivo en frente de mi casa hay montañas, tenemos una finca, hay vacas. Cerca de la casa en el pueblo pasa el Río Cauca. Es un pueblo muy tranquilo donde los vecinos son amigos y se conocen todos desde la infancia. Somos muy unidos en ese sentido. Para mí, mi pueblo es muy bonito.

Mi abuelo era agricultor, tenía unas tierras y cultivó la caña, también tenía molienda y se hacía la panela. Mi mamá era ama de casa y yo estaba más que todo con ella, al lado de ella siempre.

Me dediqué a trabajar de niñera. Después conseguí a mi esposo y tuvimos a la niña. Tenemos una hija de 16 años. El sueño de ella es estudiar una carrera. Ella ya tiene sus metas.

Con el tiempo se puso la situación difícil allá en el pueblo. Mi marido tomó la decisión de venirse para acá para Chile. Porque él decía si nosotros queremos darle una vida buena a la niña, una educación, ahí en el pueblo no se puede. Él se vino primero y por cuatro años no nos vimos. Fue bastante duro.

Ya con mi hija llevamos seis meses acá. Al principio fue muy difícil todo. A donde llegamos es una toma. De donde yo vengo las casitas son pequeñas, pero son bonitas. Y de allá a una toma. Cuando yo llegué había un basurero ahí al pie de donde nosotros vivimos. Se me bajó mucho la moral al principio.

Pero mi hija ya se ha podido ir al colegio. Acá nos da la oportunidad de ayudarla a ponerse a estudiar. Venir acá fue una buena decisión a pesar de las dificultades.

Bueno y ahora nos dimos cuenta que yo estoy embarazada. Ya con otro bebé es otra cosa más diferente. Pero con la ayuda de Dios todo va a salir bien.

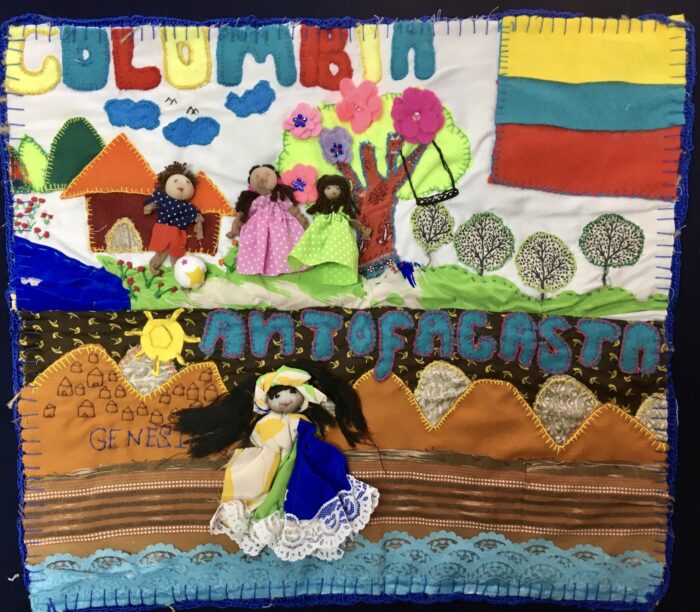

Arpillera by Dalia Liseth Argüello Mosquera

Read Dalia Liseth's story below

My arpillera shows the bright colours of my country in the upper part. This house is where we lived when we were little. Next to the house there was a river and in the garden there was a big tree with a swing. My two brothers and I played there a lot — I’ve shown them here. The bottom part of my arpillera shows the hills of Antofagasta. I made little houses to represent the campamento where we live now. That figure there is my mother, she’s very dedicated to organising and activism in the campamento. And here is the sea, because from the hills we look down and see the sea. It’s very beautiful.

I’ve known my husband since I was 11. We’ve been together for 18 years now. I arrived here in Antofagasta when I was 23. My son was six or seven years old. My mum was already here and she told me to come. There were 40 people on the bus. The trip is so long that we all became friends—we danced, we talked, we laughed.

When we were arriving into Antofagasta on the bus, the city seemed so strange to me. In my country, they say that there are campamentos like this, but I had never lived in one or seen one. That first impression was tough. My plan was just to come for a short visit. But things happened along the way. I fell pregnant. It’s been six years now and we haven’t even been back to my country once.

We have a very different culture. Colombia is a poor country, but when it comes to celebrations, it’s the best. We’ll barely have enough to put food on the table, but if there’s an occasion for a party, we’ll find the money! My first year here, there was a party at my son’s school. My husband and I got all dressed up. I fixed my hair, put on a long dress, an evening bag — all very elegant. Then when we got there, the mums were in flip flops! It turned out the party was making completos (Chilean hotdogs) for the kids!

Here I have all my papers in order, I have a job. There are people who don’t have any of that, so I am grateful. But so far I haven’t really enjoyed being here. I got carpal tunnel syndrome from my cleaning job. They’ve scheduled me for surgery. The surgeon has given me a medical certificate that states I shouldn’t do any kind of cleaning.

My husband is working in Spain now and we’re all planning to go. But I did try to make my home here. Although it’s not very pretty, it’s not much, now that we are thinking about leaving, I feel attached to it.

Mi arpillera tiene en la parte de arriba los colores vivos de mi país. Esta casa es donde vivíamos cuando éramos pequeños. Al lado de la casa había un río y en el patio había un árbol grande con un columpio. Ahí jugamos mucho con mis dos hermanos, quienes están representados aquí. En la parte de Antofagasta está el cerro. Hice casas pequeñas que representan los campamentos donde vivimos, y la que se encuentra ahí es mi madre, quien está muy dedicada a la organización del campamento. Y aquí el mar, porque desde el cerro miramos hacia abajo y vemos mucho mar. Eso es muy bonito.

Mi esposo lo conocí desde que tenía 11 años. Ya llevamos 18 años juntos. Yo llegué aquí a Antofagasta con 23 años. Mi hijo tenía como seis, siete años. Mi mamá ya estaba acá y me dijo que viniera. Vinimos en bus directo desde Cali. Éramos 40 personas. Es tan largo el viaje que todos nos hicimos amigos — bailamos, hablamos, reímos.

Cuando íbamos entrando en bus a Antofagasta, se me hizo tan extraña la ciudad. En mi país dicen que hay campamentos así, pero yo nunca había vivido en uno ni los había visto. La primera impresión es dura. El plan mío era visitar e irme luego. Pero en el camino van pasando cosas, quedé embarazada. Ya llevamos seis años y no hemos ido ni una vez a mi país.

Tenemos una cultura muy diferente. Colombia es un país pobre, pero para la fiesta, es lo mejor. No hay plata ni para comer supuestamente, ¡pero para la fiesta sale plata! El primer año acá, hubo una fiesta en el colegio de mi hijo. Con mi marido pusimos la mejor pinta. Arreglé el cabello, me puse un vestido largo, una cartera, todo bien elegante. ¡Cuando llegamos allá, las mamás estaban en chanclas! La fiesta era que había que ir a picar tomate para hacer completos [perritos].

Acá tengo mis documentos, tengo trabajo, y en este momento hay gente que no tiene nada de eso, así que yo agradezco. Pero hasta ahora a mí no me he gustado mucho la experiencia. Me dio el síndrome del túnel carpiano debido a mi trabajo en aseo. Me programaron para cirugía. El traumatólogo me dio un papel donde no me deja hacer ningún tipo de aseo.

Mi marido ahora está en España y pensamos irnos todos. Igual aquí traté de hacer mi hogar. A pesar de que no es muy bonito, no es mucho, ahora que pensamos en irnos, a uno le da apego.

Arpillera by Emilse Robledo

Read Emilse's story below

My arpillera is called ‘Gratitude’. All these colours that you see in this part here are what I see if I close my eyes and travel back to my village. And here are the hills of Antofagasta. Seeing the hills takes me back to when I arrived here with a suitcase full of hopes, dreams, debts.

This part here is a combination of river and sea. Here in this suitcase are the six countries I have been able to visit, thanks to God. The church that is shown here is my everything. And here are my daughters, there I am, and there is my husband. The family we made, thanks to God’s blessing.

I am a chef and bearer of traditions, appointed in Cali by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. My objective is to salvage, safeguard, strengthen, and make visible the gastronomy and culture of the Department of Chocó. I descend from Africa where there is a culture of bright colours, dance, many things that we have kept alive here. So I represent my culture through gastronomy, through dance, through theater, through my presence.

I am from the centre of Chocó, from the rural river region. We lived in a colourful house, a beautiful house. From the age of seven or eight we learned to work the land, to cut wood, to weed, and to take care of animals. I come from a large family, I am one of 11 siblings, with different mothers. I am one of the eldest. My mum passed away 24 years ago. She was very young, she died at the age of 33. My dad’s income was not enough, so we went hungry, we had very little. It was a very hard childhood, but I think I was a happy girl despite that precariousness.

I had my first daughter very young, at 16. I was a single mother, I had no job. I had to migrate to the city, to Cali. I arrived at the height of the period of violence and conflict there. But I have always been resilient. I started working as a waiter, and I ended up falling in love with gastronomy. After 14 years as a waiter, I went on to study gastronomy. I dreamed of having my own restaurant and by God’s blessing I was able to establish one before I graduated. I had my own restaurant, and it still bears my name.

I left my country because I was heavily indebted to loan sharks. Here in Chile I was able to resolve that situation. But I felt so much sadness because I couldn’t be with my daughters. They had to stay in Colombia and it was a torment not to be with them.

In the end, Chile has been a country that has blessed me. It has cost me pain, tears, money, discrimination. But everything that I have gone through to be able to live what is expressed here in this arpillera has been worth it.

Mi arpillera se llama ‘Gratitud’. Todos estos colores que ves acá es como si yo cerrara mis ojos y viajara hasta mi pueblo. Y acá están los cerros de Antofagasta. Ver los cerros me remonta a cuando llegué aquí con una maleta llena de ilusiones, de sueños, de deudas. Lo que hice aquí es una combinación entre río y mar. Acá en esta maleta están plasmados los seis países donde Dios me ha permitido ir, que ha sido un sueño. La iglesia que está acá es mi todo. Y por acá están mis hijas, estoy yo, y está mi esposo. La familia que conformamos actualmente por la bendición de Dios.

Soy chef y portadora de tradiciones, nombrada en Cali por la Secretaría de Cultura y Turismo. Tengo como objetivo rescatar, salvaguardar, visibilizar, empoderar la gastronomía y la cultura del Departamento del Chocó. Yo desciendo del África dónde hay una cultura de colores fuertes, del baile, de muchas cosas que siguen por aquí. Entonces represento mi cultura a través de la gastronomía, a través del baile, a través del teatro, a través de mi presencia.

Soy del centro del Chocó, soy de río. Vivíamos en una casa colorida, una casa bonita. Aprendimos desde los siete, ocho años a trabajar la tierra, cortar madera, deshierbar, cuidar los animales. Vengo de una familia numerosa, somos 11 hermanos, de distintas madres. Nosotros somos los mayores. Mi mamá falleció hace 24 años, muy joven, con 33 años murió. El sueldo de mi papá no alcanzaba, pasábamos hambre, pasábamos muchas necesidades. Entonces fue una niñez muy dura, pero pienso que era una niña feliz a pesar de esa precariedad.

Muy temprano tuve a mi niña, con 16 años. Era madre soltera, no tenía empleo. Me tocó migrar a Cali. Cuando llegué, estaba en el apogeo de la violencia. Pero siempre he sido resiliente. Empecé a trabajar de garzona, y ahí me terminé enamorando de la gastronomía. Después de 14 años, me retiré para estudiar la gastronomía. Soñaba con tener un restaurante y Dios me dio la bendición de tenerlo antes de graduarme. Tuve mi restaurante que aún conserva mi nombre.

Yo dejé mi país porque estaba llena de deudas de gota a gota [prestamista informal] y aquí en Chile pude resolver esa situación. Sentía mucha tristeza porque no podría estar con mis hijas. Se tuvieron que quedar en Colombia y me tenía atormentada no estar con ellas.

Al final, Chile ha sido un país que me ha bendecido. Me ha costado dolor, lágrimas, dinero, discriminación. Pero todo lo que he pasado para poder vivir esto que está aquí plasmado en la arpillera ha valido la pena.

Arpillera by Idalia Rivera

Read Idalia's story below

My arpillera reflects the multiculturalism of the campamento, the informal settlement where I live. The campamento is rich: rich in culture, in knowledge, in children, in diversity. We made this campamento ourselves. It was a desert and we transformed it into a landscape. It is a well built town, built with faith, with strength, with labour borne by love. In the arpillera workshops I have been able to recreate this. In the workshops we sit, talk, work. We make stories.

Sitting down to make the doll figures in the arpillera workshops takes me back to my childhood, to the countryside in the south of Colombia. When we were little, we always wanted to play with dolls, and since my mother didn’t have enough money to buy any, we made rag dolls. We made them out of any old piece of cloth and for the hair we used the fibres from cobs of corn.

My childhood was in some ways very happy but in others very sad. Happy because I had a lot of brothers and sisters and we loved each other, we took care of each other. But sad because we experienced a lot of hardship. My mum was a single mum. We lived off the fruit we harvested.

We would climb the trees, knock down the mangoes, and collect them in 20 sacks. Totumos [gourds] as well. To harvest the totumo, we had to get up at 4:30 in the morning and go to the forest. After harvesting them, we took them home in sacks on our heads. Then they were boiled in water and dried out in the sun to turn them a beautiful white, to be used as containers. It brings back a lot of emotions when I see those totumo trees. It is my culture and it is wonderful.

After the harvest my mother would have to leave for two or three days to sell the fruit and the totumos, and we stayed at home in the countryside, where it was very isolated. Being alone like that put us in danger of violence, of rape. That happened to me. Rape at nine years old. It was so, so tough. There was no psychologist. It happened and I just had to continue working. But I was able to get over it on my own, asking God to give me strength.

Many years later, I was one of the first to arrive here at the campamento in Antofagasta. There were just three houses. Now there are 500 families, about 2,250 people. I have been a community leader for eight years. It has been a challenge, managing our community with the other organisers. It has been very difficult but not impossible. It is incredible that we live in the middle of a place they said, and still say, is not livable. It is a wonder. We have come here to contribute, to make this place beautiful.

Mi arpillera refleja la multiculturalidad que tenemos en el campamento donde vivo. Vivo en un campamento rico: rico en multiculturalidad, en conocimientos, en infancia, en diversidad. Es un campamento que lo hicimos nosotros. Siendo un desierto, lo convertimos en un paisaje. Es un pueblo bien construido, construido con fe, con fortaleza, con una mano de obra que viene del amor. En los talleres de arpillera he podido recrear eso. En los talleres nos sentamos, dialogamos, trabajamos. Hacemos historias.

Sentarme a hacer los muñequitos en los talleres de arpillera me devuelve a la infancia, al campo en la zona sur de Colombia. Cuando éramos niñas siempre queríamos jugar a las muñecas, y como mi mamá no tenía con que comprar una muñeca, hacíamos las muñecas de trapo. Las hacíamos de cualquier trapito y para el pelo le colocábamos el pelito de choclo, de mazorca.

Mi niñez fue una niñez muy alegre pero también muy triste. Alegre porque éramos muchos hermanos y nos amábamos, nos cuidábamos entre nosotros. Pero triste porque vivíamos sufrimientos. Mi mamá fue mamá soltera. Vivíamos de la fruta que cosechábamos.

Nos subíamos a los árboles, tumbamos los mangos, y los recogíamos en 20 sacos. También el totumo [un tipo de calabaza que crece en los arboles]. Para cosechar el totumo, teníamos que levantarnos a las 4:30 de la mañana para ir al monte. Después de cosecharlos, los cargábamos en sacos en la cabeza para retornar a la casa. Se cocinan en agua y se secan al sol y se quedan blanquitos hermosos, para usar como recipientes. Me emociono cuando veo esos árboles de totumo. Es algo que es tu cultura y es una maravilla.

Después de la cosecha mi mamá tenía que ir por dos, tres días para vender la fruta, el totumo, y nosotros quedábamos en el campo en la casa muy solos. Al estar solos, nos ponía en peligro de violencia, de violaciones. Eso viví yo. Una violación a los 9 años. Era tan difícil, tan duro. No había psicólogo. Pasó y tenía que seguir trabajando. Pero lo pude ir superando sola, pidiéndole a Dios que me ayudara a fortalecerme.

Mucho tiempo después, fui una de las primeras en llegar aquí al campamento en Antofagasta. Eran tres casas no más. Ahora somos 500 familias, cerca de 2.250 personas. He sido dirigente por ocho años. Ha sido para mí un desafío, manejar esa comunidad en la directiva con mis compañeras. Ha sido muy difícil pero no imposible. Es impresionante vivir en medio de donde decían, o dicen aún, que no es vivible. Es una maravilla. Nosotros hemos venido a aportar, a embellecer.

Arpillera by Isabella Ville

Read Isabella's story below

My arpillera represents my city, so you can all see how beautiful it is. It has a tropical climate and it’s called Palmira because of the palm trees. It has an airport, its economy is based on agricultural production. The church is very beautiful, it has a huge clock. Wherever you are in the centre of the city, you can see it, so you always know the time. Palmira is at once a warm and welcoming city and also dangerous and violent. I carry my city with me.

We had always lived in Palmira, my family: my father, my mother, and my four siblings. My father passed away on December 30, 1999. My mum stayed with us. We were very young and my mother was a housewife, she didn’t know what it was like to go out to work. My siblings and I had to go out and sell anything we could think of to pay the rent. We shared a 120-centimetre bed and some of us slept on the floor. We had an oil stove for cooking.

Well, we grew up and the girls, we married very young. My sister, the youngest, had her first child at the age of 13. I got married too. At around 17 I had my daughter — she’s 18 now— and four years later I had my second daughter. I also worked. All my life I have worked. I worked for 15 years in the centre of Palmira, and I know a lot about commerce and customer service.

My husband was killed eight years ago. We know who killed him, but the only one who went to the police to report him was my mother-in-law. I didn’t want to, out of fear. My mother-in-law died a year ago and then the guy who killed my husband appeared. He went and broke the windows of the house we rented, he threatened me.

I had to migrate because of violence. I had to bring up my daughters alone.

Mi arpillera representa mi ciudad, pues para que conozcan cuan hermosa es. Es un clima tropical, se llama Palmira por las palmeras. Tiene aeropuerto, tiene fábricas agrícolas. La iglesia de Palmira es muy bonita. Tiene un reloj grandísimo, en todo el centro usted mira ahí donde sea y se sabe qué hora es. Palmira es una ciudad muy acogedora pero también es muy peligrosa, muy violenta. Llevo mi ciudad siempre presente.

Siempre habíamos vivido en Palmira. Era mi padre, mi madre, y los cuatro hermanos. Mi padre falleció el 30 de diciembre de ’99. Quedó mi mamá con nosotros. Éramos muy chiquitos y mi mamá era una señora de casa, no sabía lo que era salir a trabajar.

Mis hermanos los mayores tenían que salir a buscar la comida y nosotros ir a vender rifas o cualquier cosa para poder pagar el arriendo. Compartíamos una cama de 120 centímetros y unos dormían en el suelo. Teníamos un fogón de petróleo para cocinar.

Pues, crecimos y nos casamos muy jóvenes las dos mujeres. Mi hermana, la menor, tuvo su primer hijo a los 13 años. Yo me casé también. Como a los 17 tuve a mi hija, que en este momento tiene 18 años, y cuatro años después tuve a la segunda. También trabajé. Toda la vida he trabajado. Trabajé 15 años en el centro de Palmira, y sé mucho del comercio y la atención al público.

A mi esposo lo mataron hace ocho años. Ahorita el 15 de julio [de 2022] se cumplen ocho años. La única que puso demanda contra el muchacho que le mató fue mi suegra. Yo no lo quise hacer por miedo. Mi suegra se murió hace un año y entonces aparece el muchacho. Fue y quebró los vidrios de la casa que arrendábamos, me amenazaba.

Me tocó migrar por la violencia. Me tocó sola sacar a mis hijas adelante.

Arpillera by Luz Amparo Uribe Noreña

Read Luz Amparo's story below

My arpillera represents the countryside near Medellín and the sea beside Antofagasta. In the lower part of the arpillera, I wanted to show a drawing that I did when I was at primary school, which won a prize. It depicts the countryside where I spent my childhood holidays — the gully, the bridge, the forest. They grow coffee there, it’s mountainous and very green. And at the top of the arpillera is the sea beside Antofagasta. As a migrant, I have been amazed by the sea. It’s always nearby, I see it every day when I go to work. And in the summer it’s wonderful to go swimming, super refreshing.

My mother passed away when I was very young, I was eight years old. My father remarried. So, we spent our holidays in the countryside where my stepmother’s parents lived. I’m from the city, from Medellín, but I really enjoyed the countryside: climbing trees, eating fruit, going to the streams to catch little fish, all this gave me a very beautiful childhood.

Medellín back then was beautiful, calm. As time went by, after I was married and had my children, Medellín became very violent. When you live in a neighborhood with crime and violence, it is very, very scary. One of your children goes out to work, you hear a gunshot and you think: ‘Ay, what if something’s happened to him?’

I was a young mum. I got married at 19 and at 20 I already had my first little one, and I had my second at 28. Well, there was a lot of domestic violence, and you don’t want that for your children. So I basically had to be a single mum. I worked in a school doing cleaning and I had to keep an eye on everything, ‘Like a general’, my son tells me!

I feel very proud of my children. The youngest went to Argentina to study and then to work. He got a university degree; he works at Nickelodeon. The eldest is here in Antofagasta and is doing very well. He has worked at Sky Airlines and at the Tottus supermarket chain.

Back in Colombia, once my children left, I was going to be alone. What exhausted me most about Medellín was the violence. I arrived in Antofagasta on April 27, 2018, at the invitation of a friend of mine, who had me to stay initially. And I can say that I’ve been happy since that day. Antofagasta has welcomed me well.

The truth is I don’t want to go back to Colombia. I just want to visit my dad. But I’m waiting for my permanent residency visa to be able to go back without worrying about my visa status. I have all my papers up to date, my taxes, everything. I’ve been waiting for almost three years now for a response to my visa application, and it should only take six months.

I have many ideas and projects here, like I want to start a small grocery store, which I’m already working on.

Mi arpillera representa el campo cerca de Medellín y el mar de aquí, de Antofagasta. Quería reflejar en la parte inferior un dibujo que hice cuando estudiaba en la primaria, que fue uno de los que ganó un premio. Representa el campo donde pasaba las vacaciones de mi niñez —la quebradita, el puente, el bosque. Allá es donde crece el café, es montañoso y muy verde. Y en la parte superior está el mar de Antofagasta. Como migrante, me ha impactado el mar, que está siempre ahí. Todos los días lo veo al ir a trabajar. Y en el verano es delicioso ir, súper rico.

Falleció mi mamá cuando yo era muy pequeña, tenía ocho años, y mi papá se volvió a casar. Entonces, las vacaciones las pasábamos en el campo donde los padres de mi madrastra. Soy de ciudad, de Medellín, pero disfruté mucho del campo. Trepar árboles, comer fruta, ir a los arroyuelos a coger pescaditos, todo eso me hizo una infancia muy bonita.

Medellín en ese entonces fue bonito, tranquilo. Al pasar el tiempo, ya después de casarme, de tener a mis hijos, Medellín se volvió muy violento. Cuando vives en un barrio donde hay delincuencia y violencia es muy muy aterrador. Si salía un hijo a trabajar, al oír un tiro, uno decía: ‘Ay, será que le pasó alguna cosa’.

Yo fui mamá joven. Me casé a los 19 y a los 20 ya tenía mi primer cachorrito, y tuve el segundo a los 28 años. Pues, hubo mucha violencia intrafamiliar, y uno no quiere eso para los hijos. Entonces prácticamente me tocó ser mamá soltera. Trabajaba en un colegio haciendo aseo y yo tenía que estar pendiente de todo. ¡’Como un general’ me dice mi hijo!

Me siento muy orgullosa de mis hijos. El menor se fue a Argentina a estudiar, a trabajar. Es profesional, trabaja en Nickelodeon. El mayor está aquí en Antofagasta y está muy bien, gracias a Dios. Ha trabajado en Sky, en Tottus.

Entonces ya mis hijos se fueron y me iba a quedar sola. Lo que más me tenía aburrida en Medellín era la violencia. Llegué a Antofagasta el 27 de abril de 2018 por una amiga mía, quien me recibió. Te digo que soy feliz desde ese día. Antofagasta me ha acogido bien.

La verdad yo no quiero volver a Colombia. Solo para visitar a mi papá, pero estoy esperando la definitiva [visa de permanencia definitiva] para poder ir tranquila. Tengo todo al día, las imposiciones, todo. Ya llevo casi tres años esperando, y se debería demorar solo 6 meses.

Aquí tengo muchos proyectos. Como poner un pequeño negocio de abarrotes, ya un proyecto mío.

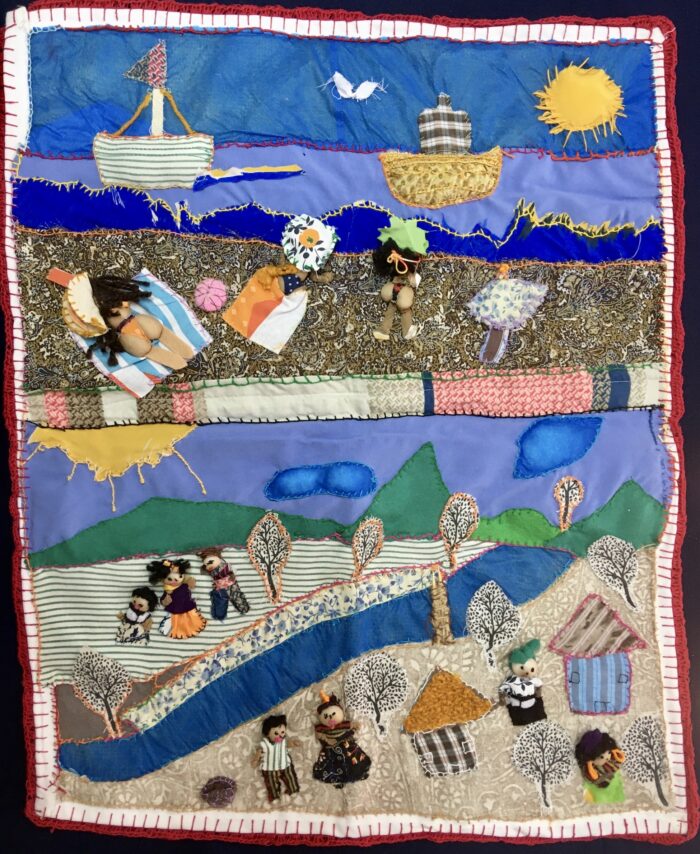

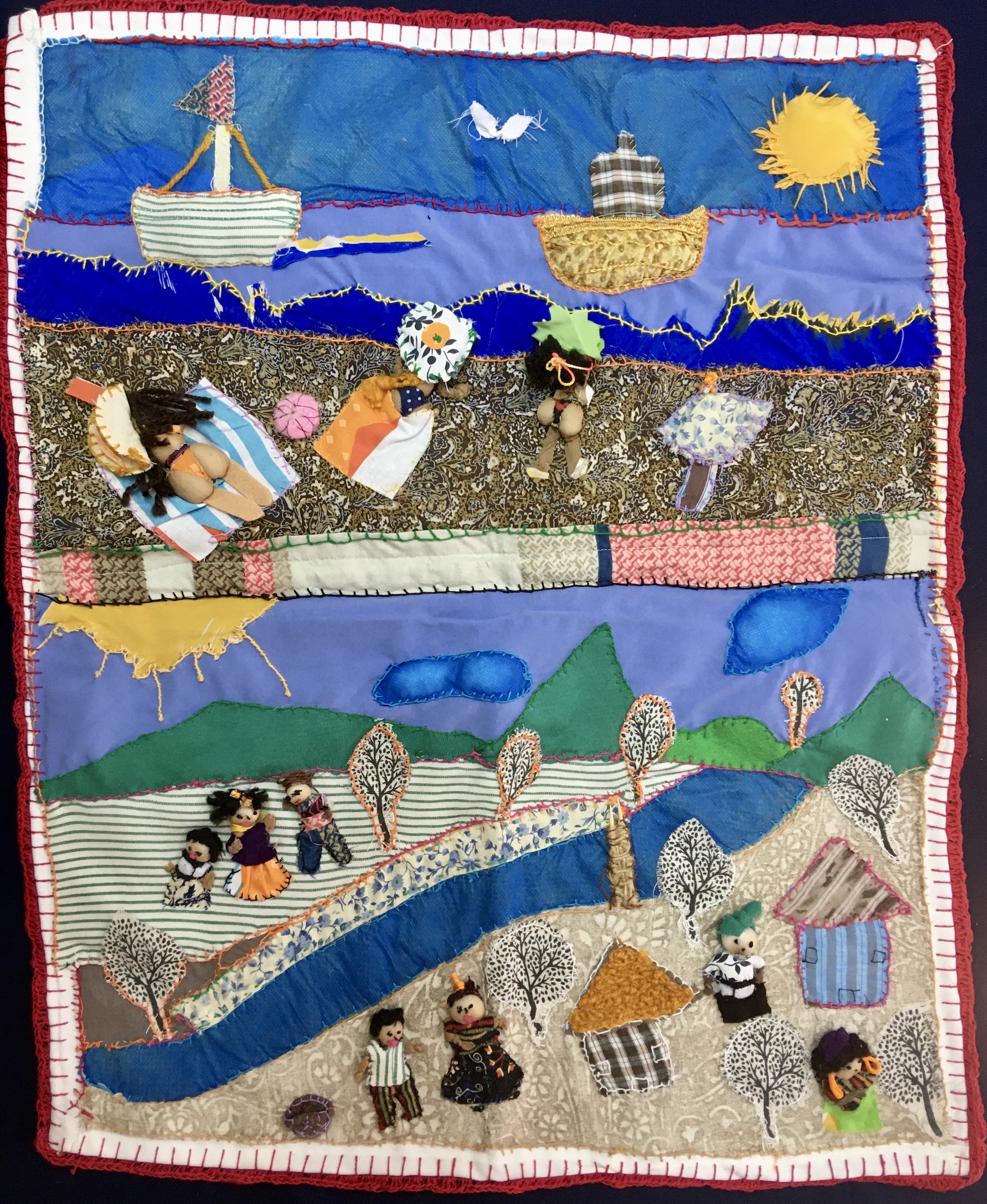

Arpillera by Miryan Montoya Gutierrez

Read Miryan's story below

My arpillera represents the place where I live in Genesis II, Antofagasta. The house where I live has a balcony, you look out from the balcony and right there is the sea, you can see the boats. And here are the steps that go up to the house, which is on a hill. My sister keeps the entrance to the house very pretty with lots of flowers in the front garden. And here I’ve shown us on the balcony — me, my sister and the neighbour who lives next door.

In Colombia, we lived in San Pedro de la Victoria, a medium-sized rural sector; not so big and not so small. I lived with my mum and I was her support. My mum has a house in Colombia but it’s a humble little house, it doesn’t have a kitchen.

In Colombia, I worked doing different things. I worked for five years on the highway while they were fixing the road. I walked pulling a handcart along the line of traffic selling the drivers and passengers grape juice and water from a styrofoam cooler box. When they finished fixing the road, I went to work with my friend in a chicken shop for about four years.

My niece told us that there were better life opportunities here in Chile. We had to borrow money to pay for the flight. I came on a plane from Cali to Panama and from Panama to Santiago. Then from Santiago to here, Antofagasta, I came by bus.

Here in Antofagasta I work as a cleaning assistant. I still send my mum money for shopping and food and to pay for electricity, energy, any medicine she needs, all those things. My dream is to buy my mum a new kitchen.

Mi arpillera representa el lugar donde vivo en Genesis II, Antofagasta. Hay un balcón en la casa donde vivo, y en el balcón mira uno y está el mar, se ven los botes. Y acá están las gradas para subir a la casa, que está en la loma. La entrada de la casa la tiene muy linda mi hermana, mucha flor en su jardín. Y acá estamos unas personas en el balcón, yo, mi hermana, la vecina que está al ladito.

Nosotros en Colombia vivíamos en San Pedro de la Victoria, un corregimiento no tan pequeño ni tampoco tan grandote. Vivía con mi mamá y yo era su sustento. Mi mamá tiene casita en Colombia pero es una casita humilde, no tiene cocina.

En Colombia trabajé en diferentes cosas. Trabajé cinco años en la carretera donde estaban arreglando la vía. Trabajaba vendiendo jugo de uva y agua en un carro con nevera de icopor [plumavit] puerta a puerta. Se reparó la carretera y entonces me metí a trabajar con mi amiga en un asadero de pollo como unos cuatro años.

La hija de mi hermana nos dijo que había más oportunidad de vida acá en Chile. Nos tocó pedir prestado dinero para poder pagar el vuelo. Yo me vine en un avión de Cali a Panamá y de Panamá a Santiago. De Santiago hasta aquí, Antofagasta, fue en bus.

Acá trabajo como auxiliar de aseo. Desde acá a mi mamá yo le envío todavía para las compras y la comidita y para pagar los servicios de luz, energía, algún remedio que necesita, todas esas cosas. El anhelo mío es regalarle a mi mamá su cocina.

Arpillera by Pepita

Read Pepita's story below

My arpillera is about my working life here in Chile. When I first arrived, I got a job taking care of two girls. The family was so kind to me. I had a contract to work with them for two years. And during that time, I got my degree certificates apostilled because I wanted to work in nursing here. Now, my job day-to-day is working with patients, administering medications, monitoring their vital signs. Thanks to God, so far I’ve been doing well. My profession is a vocation.

In Colombia, I grew up with my aunt, a language teacher. She raised me from the age of eight until I was 22 years old. She lived in the Chocó department. I went to primary school at the María Montessori School in Quibdó and I got my secondary education at the Carrasquilla Integrated Industrial Institute.

Then I went to Buenaventura where my mum was, but I didn’t like it. It’s very hot and rainy, such a sticky heat! From Buenaventura I went to Cali, and there I fell in love. I had my son, the eldest, who is 40 now. I fell in love with a policeman. We were about to get married, but I didn’t go through with it and we separated.

Then I met my second partner. He was a lovely person and looked after me very well. But when he drank, he made my life miserable. He threatened me, he shouted at me, he made two attempts on my life. Given all of that, I separated from him in 2006.

In 2004, I started studying nursing. And in 2009 I decided to come to Chile. I came with two friends, just to visit at first, but I decided to stay. I was motivated to stay here because it gave me peace of mind. I didn’t want to see the father of my children again. At first I cried because I had never lived so far away from my family and friends. But then I got used to it. I’ve only been back to Colombia once in 13 years.

My three children are here. I bought a plane ticket for each of them to come. They have done well. One works in human resources, another in logistics, and the other in a restaurant.

I’ve also been part of dance and theatre groups here. Back in Colombia I danced too. Here I started out in the Colectividad de Residentes Colombianos en Antofagasta [Colombian Residents in Antofagasta Collective]. Then we put together a theatre group. We put on a play, ‘Xenophobia’, and it began to raise awareness about discrimination. We have performed in many places. We have shared our culture widely.

Mi arpillera se trata de las funciones que estoy realizando acá en Chile. Cuando primero llegué me salió un trabajo para cuidar a dos niñas. La familia era bella gente conmigo. Allí estuve dos años con contrato. Y durante ese tiempo mandé a apostillar mis certificados porque quería trabajar en enfermería aquí. Ahora en lo diario mi trabajo es tratar con pacientes, administrar los medicamentos, controlar sus signos vitales. Gracias a Dios hasta hora me ha ido bien. Mi profesión es una vocación.

En Colombia yo me crie con mi tía, profesora en idiomas. Ella me crio desde los ocho años hasta que tuve 22 años. Vivía en el Departamento del Chocó. Estudié en el Instituto Integrado Carrasquilla Industrial y la primaria la estudié en la Escuela María Montessori, allá en Quibdó.

Después fui a Buenaventura donde mi mamá, pero no me gustó Buenaventura. Mucho calor y lluvia, ¡un calor pegajoso! De allí me quedé en Cali, allí me enamoré. Tuve mi hijo, el mayor, que ya tiene 40 años. Me enamoré con un policía. Estábamos para casarnos, pero yo no me casé, nos separamos.

Ya conocí mi segunda pareja. Bella gente, me tuvo muy bien. Pero cuando tomaba los tragos, me hacía la vida imposible. Me amenazaba, me decía palabras, atentó dos veces contra mi vida. En vista de eso, me separé en 2006.

En 2004 había empezado a estudiar enfermería. Y en 2009 me decidí para venirme para Chile. Vine con dos amigas más, vine a conocer. Y ya me quedé. Me motivó quedarme acá por la tranquilidad y porque no quería ver más al papá de mis hijos. Al principio yo lloraba porque nunca había salido así tan lejos. Pero después me acostumbré. He ido a Colombia una sola vez en 13 años.

Ya están acá mis tres hijos. Compré un pasaje en avión para cada uno para que vinieran. Les ha ido bien. Una trabaja en recursos humanos, otro en logística, y el otro en un restaurante.

También acá he participado en grupos de baile folclórico y teatro. Allá en Colombia bailaba también. Acá empecé en la Colectividad [de Colombianos Residentes en Antofagasta]. Allí bailamos. Después armamos un grupo de teatro. Montamos una obra, Xenofobia, y allá la gente empezó a concientizarse sobre la discriminación. Nos presentamos en muchos lugares. Hicimos conocer bastante nuestra cultura.

Arpillera by R.A.R.T.

Read R.A.R.T's story below

My arpillera is about what we have experienced since I arrived here with my sister and my mother. It is my first trip outside of Colombia. Everything is so different: the way people talk, the food, everything. I haven’t been out that much yet because I get lost! But each day I go out a little more. I had never seen the sea, this is the first time. It’s beautiful, huge.

I was born in Chocó, but my mother took me to Cali when I was little. From the age of 10 or 11, I stayed alone in the house while my mother went to work. Later, I also took care of my sister sometimes, who is nine years younger than me, and a cousin of the same age.

When my mother came to Chile to work, she left us with an aunt, my sister’s godmother. My mum sent us money for food. I was 16. I took my sister to and from school. At school, sometimes they thought I was her mum!

My aunt was unwell and had to go on dialysis every night. Then she got really sick and passed away. It was very painful. We went to live with another aunt for a while. Then my mum started paying for an apartment just for the two of us.

I started studying a one-year degree at the National Apprenticeship Service. You had to work in your area while studying, so I worked in a hotel downtown. But I wouldn’t have wanted to stay there. You know how rich people are — because they have more than you, sometimes they don’t say hello to you, they don’t look at you.

So now finally my mum, sister and I have been able to come to Chile together. The three of us came by plane. I was a little scared of the turbulence. But the view, the sunset, was beautiful. That kept me calm.

In Antofagasta I’ve felt more comfortable, not as stressed as in Colombia. It’s easier now that I’m with my mum. I don’t feel so alone, we know more people. On Sundays, we go to church and we have a community.

Now I want to study to be a preschool teacher and become independent.

Mi arpillera se trata de lo que hemos vivido desde que llegamos acá con mi hermana y mi mamá. Ha sido mi primer viaje. Es tan diferente todo: cómo hablan, las comidas, todo. ¡Todavía no he salido tanto porque me pierdo! Pero cada vez salgo un poquito más. El mar no lo conocí. Acá fue la primera vez. Me ha parecido lindo, grande.

Yo nací en el Chocó, pero mi mamá me llevaba después a Cali. Desde los 10, 11 años quedaba sola en la casa mientras mi mamá iba a trabajar. Después también a veces me hacía cargo de mi hermana, que tiene nueve años menos que yo, y de una prima de la misma edad.

Cuando mi mamá se vino acá a Chile por primera vez, nos dejó con una tía, la madrina de mi hermana. Mi mamá le mandaba la plata para la comida. Yo tenía 16. Llevaba y recogía a mi hermana del colegio. ¡En el colegio a veces pensaban que yo era su mamá!

Mi tía estaba enferma y se tenía que hacer una diálisis cada noche. Entonces, ella se puso muy mal, mi tía, y falleció. Fue muy doloroso. Nos fuimos con otra tía un tiempo. Después mi mamá comenzó a pagar un apartamento para las dos.

Yo entré a estudiar en el SENA (Servicio Nacional de Aprendizajes) una carrera de un año. Había que trabajar del estudio que uno estaba haciendo, así que trabajé en el centro, en un hotel. Pero no me hubiera gustado quedarme allí. Ud. sabe cómo es la gente de plata—porque ellos tienen más que uno, a veces no saludan, no te miran.

Ahora a Chile vinimos con mi mamá y mi hermana. Las tres en avión. Me dio un poquito de miedo la turbulencia. Pero la vista, el atardecer, estaba bonita. Eso me mantenía calmada.

Por ahora en Antofagasta me he sentido más cómoda, no tan estresada como en Colombia. Ya está más fácil, ahora que estoy con mi mamá. No me siento tan sola, conocemos más gente. Los domingos nos vamos a la iglesia y allá compartimos.

Ahora quiero estudiar para maestra infantil [educadora de párvulos] e independizarme.

Arpillera by Yully H

Read Yully's story below

My arpillera is about a small part of my life here in Chile. When I first arrived, I set up a stall selling fried food. Empanadas, stuffed potatoes, chicharrón, meat skewers – a little bit of everything. I started working in a cleaning company too, but I never stopped my fried food stall. I was doing super well. Later, due to the pandemic, due to the cold, business really dropped off. I’m thinking now of doing breakfasts instead. I could get up at six in the morning, at seven the fire would already be lit so the children would leave for school fed, with some bread and some milk in them.

I have two mums. The one that gave birth to me and the one that raised me – she was my mum’s sister. She always made party food, cakes, decorations, did nails, did hair. I learned all that from her. That was the inheritance she left me. So, when I arrived here in Chile I said to myself: ‘You have got to get cooking.’

I’m from Buenaventura, but I really like to travel. I have always been a cusumbosolo, a lone ranger. I travelled through various parts of Colombia and then I went to Peru. I got to know so much of Peru, and then I stayed for a while in Tacna. After living in Tacna, I decided to come here to Chile.

I started working here in Antofagasta on a visa subject to a contract, which meant I had to stay with the same employer for two years. I had this drama where they stole six months’ salary from me. My boss had me up to my eyeballs in work, plus she yelled at us all the time. Now I’ve got another job cleaning in a supermarket, and so far, so good. They’ve congratulated me for my hard work.

I have two kids. A boy and a girl. I send them money monthly and talk to them every single day. Back in Colombia I can’t give them anything. The salary I earn there isn’t enough to pay the rent and give them food, let alone little gifts.

The father of my children is dead. It’s been two years now since he was killed by a stray bullet. When he died, people were so shocked and sad because he was a very happy person. He sold vegetables or collected and sold scrap metal on horseback. His parents adored him. Two months after he was killed, his father, my children’s grandfather, died of grief.

Now my children live with their grandmother. I just want them to study, to learn. I’m hoping to buy them a little house there in Cali, which I’ll put in their names.

Mi arpillera se trata de una partecita de mi vida aquí en Chile. Cuando recién llegué, puse un puesto vendiendo fritanga. Empanadas, papa rellena, chicharrón, chuzos de carne, de todo un poquito. Empecé a trabajar en una empresa de aseo también, pero nunca dejé la fritanga. Me iba súper bien. Después, por la pandemia, por el frío, bajó demasiado. Estoy pensando ahora en hacer desayunos. Me levanto a las seis de la mañana, a las siete ya el fuego está prendido para que los niños vayan al colegio con una masita, un líquido.

Yo tengo dos mamás. La que me parió y la que me crio. Era la hermana de mi mamá. Ella siempre hacía comidas para fiestas, pasteles, decoraciones, arreglaba uñas, arreglaba pelo. Yo de ella aprendí todo eso. Esa fue la herencia que ella me dejó. Entonces yo llegando aquí a Chile dije: ‘Hay que meterle a la cocina’.

Soy de Buenaventura, pero me gusta mucho viajar. Siempre he sido como un cusumbosolo [independiente y auto-suficiente]. Estuve en varias partes allí en Colombia y después me fui para Perú. Conocí muchas partes de Perú, hasta que me quedé en Tacna. Y en Tacna me decidí a venir acá para Chile.

Me quedé trabajando aquí con una visa sujeta a contrato, y con eso me tocaba durar dos años con el mismo empleador. Tuve un rollo que me robaron una plata de 6 meses de trabajo. Además, me tenía hasta el cuello mi jefa, nos gritaba a todas. Ahora entré a otro trabajo y hasta ahora bien. Me han felicitado por el buen trabajo.

Tengo dos niños. Un niño y una niña. Les mando mensual y hablo con ellos todos los días, todos los días. Allá en Colombia no les puedo brindar nada. El sueldo de allá no da para uno pagar el arriendo, la comida, darles el gusto a ellos.

El papá de mis hijos está muerto. Ya va para dos años desde que lo mataron de una bala perdida. Cuando se murió, imagínese, la gente muy triste porque era una persona muy alegre. Él vendía verduras o compraba chatarra a caballo. Era la adoración de sus papás. A los dos meses se murió el papá, el abuelito, de pena.

Ahora mis hijos quedaron con la abuelita. No más quiero que ellos estudien, que aprendan. Pienso comprarles su casita ahí mismo en Cali, ponerla a nombre de los dos.

Arpillera by Yury López

Read Yury's story below

My arpillera is about my previous job. I worked in a Chilean family’s home. They practically adopted me as a daughter. It was a blessing from God. I also learned a lot from the elderly abuelos I worked with. The abuela had degenerative Alzheimer’s. When I started working with them, she could no longer walk. But I gave her massages and we did different kinds of therapy and little by little she began to walk again. I was with her all the time, until the day she died. The experience has affected me so much that I think I will not get over it. I gave the best of myself to them. I really did it with all my heart.

My mum died when I was four years old. So we grew up with my dad, we were always with dad. My aunt also helped care for us, she has been like a mother. We grew up in a village but when I was 10 we moved to the city, to Popayán. My sisters and I studied there in a boarding school.

Once we finished school, my sister said to me: ‘Let’s start a business.’ ‘A restaurant,’ I said. I cooked and we waited the tables together. But suddenly one day, my sister fell into a diabetic coma. She was in a coma for a month and a half. The doctors told us that it was best to turn off life support. But my dad said no way. And one day, by the glory of God, my sister woke up.

I also had a boyfriend in Colombia. That was basically what forced me to come to Chile, because I broke up with my boyfriend. Oh, my boyfriend started freaking out, he was following me everywhere. And then one day he threatened me. He told me that if he saw me talking to another guy, he would kill me. So, I packed my suitcase and left.

The bus trip was super cool. I had a great time. Well, until we got to the Chilean border. When I was waiting to cross the border, before me in the queue was a pregnant Venezuelan woman. The border control officer said to her: ‘You are not going to step on an inch of my country’s soil.’ I was shocked. And then when I handed him my passport, he said to me: ‘Colombian, you aren’t either. Go back to your country.’ I had to return to Tacna, Peru. My aunt, who has permanent residency in Chile, had to come to get me and finally I managed to cross the border with her.

But hey, I’m grateful because not everyone has the opportunity to emigrate, to get to know new cultures, new people. And I am grateful to God for the time I spent working with the abuelos. The money I made allowed me to pay for medical treatment for my sister.

*Yury entered Chile in 2018 before the change to Chilean immigration law. She had all her papers in order and enough money to sustain a stay in the country. Her experience of discrimination and arbitrary rejection when crossing the border corresponds with academic research findings (for example Liberona Concha, 2015; Ryburn, 2022).

Mi arpillera se trata de mi antiguo trabajo. Hace un tiempo llegué a la casa de una familia chilena que prácticamente me adoptaron como una hija. Fue una bendición de Dios. Ahí aprendí muchas cosas de los abuelos. La abuelita tenía Alzheimer degenerativo con vejez prematura. Cuando yo llegué, ya no caminaba. Pero yo le hacía masajes y terapias y así poco a poco empezó a volver a caminar. Todo el tiempo estuve con ella, hasta el día en que se murió. Me ha marcado tanto que creo que no lo voy a superar. Di lo mejor de mí. De verdad lo hice de todo corazón.

Mi mamá se murió cuando yo tenía cuatro años. De ahí nos quedamos con mi papá, siempre con el papá. Ya con el tiempo también con mi tía, que ha sido como una mamá. Crecimos en un pueblo, pero a los 10 años nos cambiamos a la ciudad, a Popayán. Ahí nos pusieron a estudiar en un internado con mis hermanas.

De ahí mi hermana me dijo: ‘Pongámonos un negocio’. ‘Un restaurant,’ le dije. Yo cocinaba y atendíamos juntas las mesas. De repente, a mi hermana le dio un coma diabético. Estuvo así un mes y medio. Los médicos nos decían que era mejor que la desconectaran, porque estaba prácticamente muerta. Y mi papá dijo que no, que no, que no. Hasta que un día, por la gloria de Dios, despertó.

También en Colombia tenía a mi novio. Eso me obligó prácticamente a venir a Chile, porque terminé con mi novio. Ay, mi novio empezó a enloquecerse, me perseguía por todos lados. Hasta que un día me amenazó. Me decía que si él me veía hablando con alguien, me mataba. Entonces, armé mi maleta y me vine.

Mi viaje en bus estuvo súper choro. Lo pasé chévere. Bueno, hasta la frontera chilena. Cuando fui a pasar, antes que mi estaba una venezolana embarazadita. Le dijo [el funcionario de la Policía De Investigaciones De Chile]: ‘No vas a pisar ni un centímetro de la tierra de mi país’. Yo me quedé impactada. Entonces, cuando yo le pasé mi pasaporte, me dijo: ‘Tú tampoco colombiana. Regrésate a tu país’. Me tocó regresarme a Tacna. Tuvo que venir mi tía [quien tiene permanencia definitiva en Chile] a buscarme y ahí pude cruzar.

Pero bueno, estoy agradecida porque no todo el mundo tiene la oportunidad de emigrar, de conocer nuevas culturas, nuevas personas. Y doy las gracias a Dios por todo lo que trabajé con los abuelitos, con eso le pude pagar muchos tratamientos a mi hermana.

Principal funding: British Academy Small Grant SG2122211089

Additional funding: London School of Economics Latin America and Caribbean Centre; Universidad de Chile Instituto de Estudios Internacionales; Universidad de Chile Vicerrectoría de Extensión y Comunicaciones

Institutional support: London School of Economics; Universidad de Chile; Servicio Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural

Header artwork: Alice Volpi