Bolivia is a major importer of mercury on a world-scale. Pollution caused by the gold business has reached the most important urban areas of the country, while the authorities look the other way. This report is part of Historias Saludables, a training and support program for producing news stories about health and the environment, led by Salud con Lupa with the support of Internews.

Perhaps the first time most of us saw mercury was in a thermometer. Now, I have it in front of me but in more considerable quantities, stored in a small plastic bottle similar to the one that holds rubbing alcohol. The bottle is white, and on the front, it has a drawing of a bullfighter brandishing a red crutch in front of the dark silhouette of a bull with big horns. Among gold miners, El Español (The Spanish) is the most popular brand of bottled mercury.

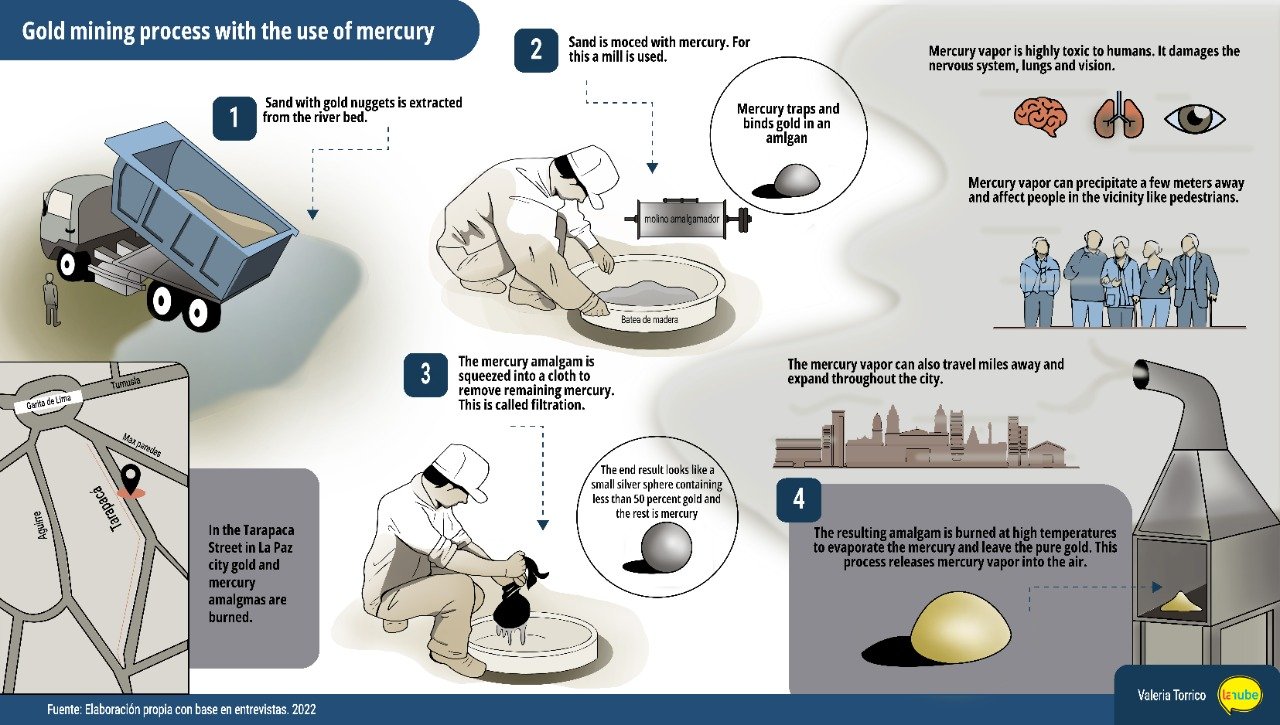

Mercury is the only stable liquid elemental metal at room temperature and has the properties of a helpful magnet to trap tiny golden granites and form an amalgam of gold and mercury. Despite its many uses, mercury is highly toxic and threatens the environment and people’s health. For example, in northern Bolivia, it is used to extract fine gold polluting the rivers and affecting the well-being of entire Indigenous communities. Many people do not know that mercury also poisons the air in cities like La Paz and El Alto, where local authorities do nothing about the pollution levels.

Tarapacá Street is close to the La Paz city center, in a bustling commercial area where street vendors occupy the sidewalks, leaving no room for pedestrians, and where vehicles are stuck in traffic. However, Tarapacá has its peculiarities. The sidewalk is not as crowded as the other streets, except for a few stalls selling raw chicken. Surveillance cameras are everywhere, protecting the windows of shops full of jewelry; this is where dealings with gold and mercury happen.

The street is famous for its many jewelry shops. The front of the buildings are full of signs: “WE BUY GOLD,” “WE MELT GOLD,” and “MERCURY FOR SALE.” The shops not only sell mercury for the mining industry, but they also burn it in artisanal ovens that emit toxic gasses into the air through chimneys.

Miners come here also to buy small plastic bottles of mercury. Each bottle contains a kilo of the metal and costs about 1,200 Bolivians ($175 USD). When sold per gram, the mercury is placed in nylon bags or another type of container.

A 70-year-old man who spent most of his life as a jeweler tells me, “Mercury is a poison.” He knows all the compounds used in this trade. He says he has managed to keep himself healthy despite working with mercury for a long time because of his attitude towards the metal; he feels a mix of respect, fear, caution, and contempt for it. Others, he says, have not had the same luck.

“And what does mercury do to you?,” I ask him through the window where he serves his customers.

“What does the poison do to you?,” he asks me instead, ironically.

Mercury scattered in the city

When the oven is on, you can hear the blowtorch in action fed from a bottle and the oxygen tanks. The steam produced comes out and into the air through the chimneys. The walls and signs are full of stains.

Usually, these ovens are used to melt gold. However, miners and dealers also come to Tarapacá Street with amalgams recently taken from the mines, some small silver balls containing mercury and less than 50 percent of gold. These balls of amalgam are burned to evaporate the toxic substance and keep the gold in its pure form.

“Yes, here we burn gold with mercury as well. The cost depends on how much mercury there is in the amalgam. Sometimes the miners bring it well squeezed; others are still watery,” a woman explains.

“When burning mercury, a lot of smoke is released into the air, which is harmful, obviously,” another dealer tells me. “I am looking at buying some machinery, a kind of a microwave that retains the smoke. I guess it is a safer way to burn mercury.” According to a research study conducted in Puno, Peru, up to 21 percent of the mercury used in the mining industry is released into the environment as steam.

Smelters, merchants, and residents in the vicinity inhale the gaseous poison, which can also spread throughout the city. The range depends on several factors, such as the height and climate, as well as the characteristics of the terrain where the emission of mercury occurs.

Mercury can travel a wide range of distances into the atmosphere; it can travel a few meters or reach the “other side of the world before it ends up in soil or water,” a publication from the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says. The metal can be spread in the form of drops, like raindrops, or as dust.

Two kilometers away and more than 4,000 meters above sea level, in the center of El Alto, the second largest city in Bolivia, gold and mercury amalgams are also burned. The steam rises in front of one of the city’s main police stations.

On Raúl Salmón Street, in the populated area of La Ceja, there are more than a dozen jewelers, many of whom have foundry ovens. “Mercury with gold? No, I don’t burn it because it produces a lot of smoke, and this is a closed space; I don’t have a chimney,” one of the smelters tells me. “Maybe further up.”

Unlike La Paz’s Tarapacá Street, here in El Alto, only three shops have metal chimneys. “Yes, we can burn here; there is no problem because we have the chimneys, and all the fumes get out,” one young man tells me. “But come back on Monday because the person who does the smelting is not here now.”

Selling without registration or precautions.

Although there are legal gaps in the country’s laws, the standard regulations (DS 24176 and DS 24782) state that mercury is a “dangerous substance,” and as such, any person engaging in its “supply, transport, storage and use” must have a registration license granted by the “relevant environmental authority.” To get a permit, people need to fulfill a series of requirements, but these are never met.

A regulation dating back almost 30 years says that the Ministry of Environment is the governmental body responsible for enforcing these rules. However, provincial and municipal authorities must also share this responsibility with the central government.

Still, the Deputy Minister of Environment, Magin Herrera, told me emphatically that municipal governments, not the central administration, are responsible for all matters related to mercury pollution in cities.

I also tried to talk with some government representatives at a municipal level in La Paz and El Alto to find out more about the pollution caused by mercury and its effects on these two cities. The Municipal Secretary of Water and Sanitation in El Alto, Gabriel Pari, told me that he did not know that in Raúl Salmón Street gold amalgams with mercury were being burned. Nevertheless, he said he would verify the information since any burning pollution occurring in his jurisdiction falls within his office’s responsibility.

Gabriel Pari added that in his municipality, there are no specific rules governing mercury transport, storage, and marketing. “It is up to the central government to issue the relevant provisions to supervise this activity and have greater control over it; but the truth is that if they were to do that, we would have 10,000 miners protesting in the streets of our cities,” he said.

My request for an interview with a representative of the Municipal Secretariat of Environmental Management went unanswered, although initially, I was reassured I would get a response.

Dealers also sell mercury in drops and plastic bags, despite the health hazards.

“No, no registration is required to sell the mercury,” one woman tells me.

“I can sell you a few drops,” says another woman when I tell her I would like to buy some mercury. She opens the bottle with bare hands, takes out a small nylon bag, and very carefully, not to waste anything, shakes a bottle of El Español and pours a few drops into the bag. “That would be 18 pesos

($2.61 USD)”, she tells me.

Bolivia is one of the top five importers of mercury in the world. According to a study conducted by the Bolivian Information and Documentation Center (CEDIB in Spanish)—a not-for-profit organization dedicated to the research of social and environmental issues in Latin America—the cities of La Paz and El Alto are the recipients of more than 90 percent of the mercury imported to the country.

The same research study indicates that mercury is transported in canning containers of 34.5 kilograms, with an approximate value of 34,500 bolivianos ($5,022 USD) each. Once it reaches the city, it is distributed in the white bottles of El Español’s famous brand.

The mercury trade is out of control. A report by Bolivia’s Ombudsman Office, issued last May, says that the authorities do not know the routes of storage, distribution, and final disposal of mercury, or at least that is what they claim.

Alleged frauds related to mercury distribution

Between 2014 and 2018, three companies handled at least 50 percent of mercury imports to Bolivia: Paloan SRL, Consumer Bolivia SRL, and Juan Orihuela Mamani Import-Export. During that period, they imported at least 341 tons of mercury for the gold mining industry for a total value of $11.3 million USD, according to CEDIB’s research. However, either these companies do not exist anymore, or it is not easy to contact them. Their telephones do not ring anymore, and their owners may have abandoned the offices several years ago. In some cases, it is not even sure they ever existed.

I asked the National Customs Office for the list of the new mercury importers that have come into the market in recent years, but at the time of closing this edition, I have not had a reply to my request.

However, the white bottles containing mercury sold on Tarapacá Street are linked to people with connections in Peru, some with dodgy backgrounds. Moreover, the El Español brand does not belong to a single company, but to several importers.

Printed in the bottles, there is an email address for Percy Fernández Vitorino, an importer who at some point studied in Peru. The data gathered by CEDIB shows that in 2018, Fernández Vitorino imported 690 kilos of mercury for a total of $20,700 USD. However, when I asked him for an interview, he sent a very brief email to say he could not talk to me. “Hello, I am sick and not in La Paz,” read the email.

In other of these small bottles, the email address that appears is the one for Alvior Bolivia SRL. I could not contact the company through that email. The owner of the house that used to be their main office told me that the company had left years ago, apparently back to Peru. Looking for more information about this company on the Internet, I found a document that would lead me to a 53-year-old widow.

She is waiting for me in her apartment, located on the fifth floor of a building in the center of La Paz. The space is barely enough for her, her 12-year-old daughter, and three rescue dogs.

Eighteen years ago, in 2004, Angélica Evelyng Uzin Vargas met the Torres Rojas family, and her life took an unexpected turn. She had recently moved to the building where she met Luis Orlando Torres Vega, his wife Olga Violeta, and their son Aldo Orlando, all of Peruvian descent. The family imported mercury through the company Alvior Bolivia SRL.

Almost immediately, they became friends, even sharing the same religion. So, when she received the news that her son had inherited nearly half a million dollars from his late father in Switzerland, she did not hesitate to share it with her new neighbors. The Torres Rojas family took advantage of such an opportunity and told Angélica that the money could grow if she were to invest it in the lucrative mercury trade. Angélica shared her version of events and testimony with me. Unfortunately, as for the other side of the story, I could not find any of the members of the Torres Rojas family to give me their version of events.

“They said they were going to fabricate an oven in El Alto, bring the raw material – mercury sulfide- from Mexico, and convert it into its liquid form to sell to the mining cooperatives,” Angélica explains, adding that they offered her significant monthly dividends. “The Alvior company had its office in the bus terminal. It used to sell mercury in La Paz, Oruro, and Potosí; they had a big clientele,” she adds.

Angelica Uzin gave the Torres Rojas family a total of $480,000 USD to invest, but she never received any of the promised profits. In 2016, when she realized that she would not recover the money, she filed a criminal lawsuit against her former friends, but by then, they had all left the country for Peru.

In 2021, the three members of the Torres Rojas family were charged with fraud. Their right-hand man, Óscar Omar Mogollón Villalba, was also investigated for his part in the scam. I tried to track him down but to no avail.

That same year, the police arrested the Peruvian family. However, in December 2021, the Prosecutor’s Office dismissed the case because of “insufficient evidence to prove that they had committed the wrongful act under investigation.” Mogollón Villalba´s case was also dismissed.

Angelica Uzin regrets the decision made by the Prosecutor’s Office to drop the case. She believes there was enough evidence to prove the scam. She told me that Mogollón Villalba is still in contact with the Torres Rojas family, his former partners, and now represents Alvior. This company would still distribute mercury on Tarapacá Street from behind the scenes.

Keeping diseases quiet

“Usually, people don’t talk about their illnesses, but I have known many who have died for keeping quiet about them. “The problem is the lungs; they get pierced,” an old jeweler tells me in his workshop. “But look at me; I’m over 70 years old and still healthy. I do not meddle with mercury. They come here to offer me to work with it, but this place is small; there is not enough space to mess with that poison. That’s why at my age, I’m still fine”.

Further on the same street, in another shop, a woman tells me: “Some people manage to survive, others never come back. They just die”.

For several years on Tarapacá Street, jewelers, dealers, and smelters have been exposed to toxic gasses. Day after day, the smoke goes out through the chimneys, people inhale the gasses, mercury evaporates, and gold remains.

“Some people end up having problems with their eyesight. But the main issue is with the lungs because of all the gasses they inhale, mercury being the most dangerous”, another jeweler tells me in a tone of resignation.

Academic studies in Costa Rica and Colombia show that mercury can impair our vision and affect the respiratory system. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), exposure to mercury vapor can cause tremors, emotional changes, insomnia, poor performance in mental function assessments, kidney damage, respiratory failure, and death. Pregnant women can pass on these ailments to the fetus; newborn babies may then develop cognitive problems and physical disabilities.

The risk does not come only from breathing air impregnated with mercury. It also comes from touching the white plastic bottles used by retail distributors and handling the amalgams. In addition, the U.S. agency warns that the skin absorbs mercury, which can cause rashes and dermatitis. I saw that when I held a small bottle of El Español. Hours later, I noticed I had tiny wounds in the fingers on my right hand, a rash caused by mercury.

There is no record of diseases or deaths caused by mercury. The subject is taboo; no one talks about it. Immunologist Roger Carvajal says that smelters and dealers are also exposed to other toxic substances that can affect their lungs and impair their vision.

Carvajal also says that if proper protective equipment is not used, the intense brightness of the metal at the time of smelting can cause damage to the eyesight. Additionally, borax, a substance also used in gold smelting, may cause lung problems if inhaled.

No one talks about the hardships caused by gold, only the profits it generates for some. In Bolivia, the gold business is booming. More and more people are engaging in gold mining activities due to the lack of other work alternatives, the tax incentives, and the high prices the metal fetches in the financial markets.

Hazardous waste

When I asked at the Tarapacá Street how I could get rid of the droplets of mercury I had bought, I was told to flush them down the toilet, “and that’s it.” Naturally, I did not take up such a suggestion; the water from the toilet ends up in the rivers used to irrigate the crops.

Instead, I called La Paz Limpia, a cleaning and waste management company that operates in the city. They told me they only deal with common solid and biohazardous waste. They suggested calling several places until I got through to the Municipal Secretariat of Environmental Management; none of the officials I tried to reach there answered my calls or WhatsApp messages.

What about the hundreds, thousands of bottles of El Español mercury sold on Tarapacá Street? What about all the gaseous mercury coming out of the chimneys there? If the matter does not disappear, as Lavoisier, the father of chemistry, said, then perhaps the streets of La Paz and El Alto are already full of mercury, which will not disappear anytime soon.

This report is part of Historias Saludables, a training and support program for producing news stories about health and the environment, led by Salud con Lupa with the support of Internews.

Reporting: Sergio Mendoza (with contributions from Yenny Escalante).

Photograpahy: Carlos Sánchez.