The Kanan Ts’ono’ot collective is making history in Mexico by demanding that cenotes be granted legal status and the Maya people named as their protectors against threats posed by industrial farming. This piece, translated for the Envrionmental Defenders series by Ruth Donnelly, was originally published by Mongabay Latam in Spanish here.

José Clemente May Echeverría has been working in the Mexican cenotes since 2015. He starts work in the first cenote at nine in the morning: following instructions passed down by his ancestors, he asks permission from the gods to enter these spaces, considered sacred to the Maya people. He then removes any leaves that have fallen into the water, sweeps the surrounding area and waits for the tourists to arrive. When they do, he invites them in to experience these natural pools, formed in the Yucatán Peninsula by the impact of a meteorite 66 million years ago.

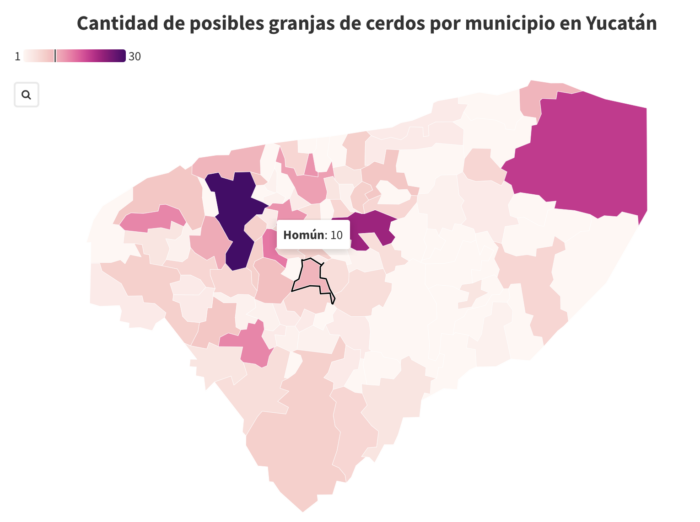

May Echeverría earns his living from tourism in the cenotes, as do half the inhabitants of Homún, a town of approximately 4,000 people located about an hour away from the city of Merida in the state of Yucatán. Homún sits within the state geohydrological reserve Anillo de Cenotes (literally “ring of cenotes”), which has been designated a Ramsar site – a name given to wetland areas of international importance.

The cenotes are the economic lifeblood of the people of Homún. With families working directly within them, as tour guides around the Anillo de Centotes, and in cafés and hotels catering for tourists who come to experience them, life in the town revolves around these ecosystems. And the townspeople in turn are the defenders of the cenotes.

May Echeverría is a member of a collective named Kanan Ts’ono’ot (“guardians of the cenotes”), made up of Indigenous Maya people of all ages.

A community united in defence of the cenotes

The collective’s story began as new roads began to be built on the outskirts of the community, without the townspeople’s prior knowledge. When they asked the authorities what was happening, they were told it was infrastructure to benefit the town. ‘That wasn’t true. The roads were to provide access for the construction of a farm with the capacity to rear 49,000 pigs,’ Lourdes Medina Carillo, the collective’s lawyer, told Mongabay Latam.

The Maya people of Homún announced their objection to this megafarm for multiple reasons; among them, potential pollution of the cenotes. In response, the company accelerated its operations.

Kanan Ts’ono’ot was formed to resolve this situation. In 2017 they organised their own consultation within the Indigenous community to ask whether people were happy with the megafarm’s operations. ‘A thorough consultation was carried out, the whole community was informed about it, several informative meetings were held. The people went out to vote and they said they didn’t want the farm. 753 voted against and 40 in favour,’ May Echeverría recalls.

The collective continued their efforts. By filing for amparo proceedings (a legal action to protect individual and constitutional rights) – in particular one petition put forward by the town’s children – they managed to halt the pig farm’s operations in 2018. Medina Carrillo clarifies that they achieved a Definitive Suspension, still in force today, but that the court has not yet reached an official verdict.

The townspeople were right about pollution from mega pig farms. This was confirmed by the Environmental Diagnostic Report on Pig Farming in Yucatán, published by the Secretary for the Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat) in March 2003.

The report included the results from an analysis of water, air, and soil quality in 20 cenotes, and concluded that these spaces ‘present indications of contamination from fresh organic matter, largely through diffuse sources of livestock wastewater, hence the presence principally of ammoniacal nitrogen and high concentrations of (the bacteria) E. coli, indicative of widespread contamination with excretions from live, warm-blooded beings.’

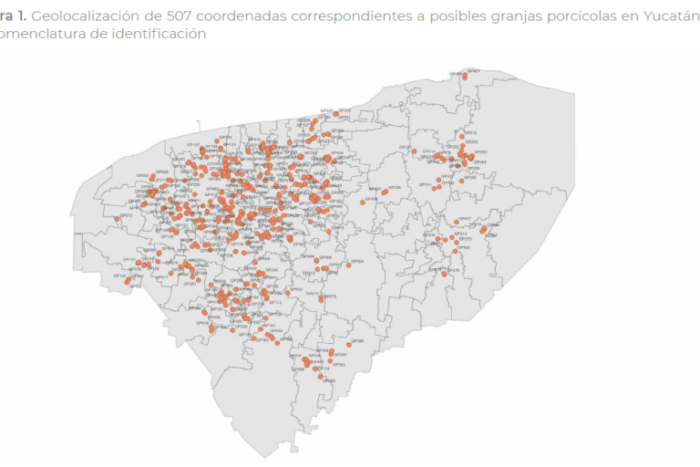

The report also identified 507 locations of possible farms in the state of Yucatán. Around 60 percent of these facilities did not hold a licence or permission to discharge wastewater.

Even more worryingly, 319 of these farms are located in territories which form part of the Anillo de Cenotes reserve. ‘We have been saying since 2017 that these farms were going to cause contamination. Now the federal government has proved us right,’ says May Echeverría.

Not just pig farms

The group realised that while they were fighting a legal battle against the farms, there were several different megaprojects causing environmental damage in the Anillo de Cenotes region, which covers 53 municipalities of Yucatán.

They decided to make an appeal to those responsible for the maintenance of the Anillo de Cenotes: the local authorities, the state governor, the president of the Republic, and the environmental authorities.

Kanan Ts’ono’ot’s members collated evidence of the presence of organochlorine pesticides – chemicals which are banned in many countries as they persist in the environment years after application. They used this information as part of a report which they submitted to the authorities in February 2022, pleading with them to put a stop to the destruction of the cenotes, and commence works of restoration and conservation.

There was no response. In March 2023, the collective filed an amparo proceeding against the authorities in question.

A Provisional Suspension was put in place as soon as the case was filed, and on 29 May 2023, the courts announced a Definitive Suspension, halting the operations of all megaprojects threatening the Anillo de Cenotes. This means, according to Medina Carillo, not only that the authorities have to stop construction of these megaprojects, but also that they have to provide answers to the collective’s concerns.

Cenotes as legal entities

Environmental law has certain limits, one of which is that measures are taken to protect specific ecosystems only when it becomes apparent that the health of that ecosystem impacts on a person or group of people. However, there have been examples in other countries, such as Colombia and Ecuador, of ecosystems being protected directly, by awarding them legal status.

For the Anillo de Cenotes to be recognised as a legal entity would be a paradigm shift for our country’s environmental justice system

Lourdes Medina Carillo, lawyer for Kanan Ts’ono’ot’s collective

‘We decided it was intolerable to wait for damage to be incurred to the population, given that the ecosystem itself has already been damaged. We looked at the examples in Colombia and Ecuador… and we realised that… you have to act if the ecosystem is already deteriorating,’ the lawyer explains.

‘For the Anillo de Cenotes to be recognised as a legal entity would be a paradigm shift for our country’s environmental justice system, but not only that. In order for it to be effective, what we need is that from here onwards the authorities are obliged to take specific, objective and clear actions to protect this area,’ she continues.

Among the demands made by Kanann Ts’ono’ot is a ban on megaprojects with the potential to cause ecological and social harm in the area, and the realisation of studies to find out what damage has already been done, which will allow them to design a restoration plan and develop strategies for its maintenance and conservation.

Vulnerable, interconnected spaces

To prove the ecological and hydrological importance of the cenotes, the collective submitted scientific reports to the courts.

Biologist Yameli Aguilar Duarte, one of the authors, explains that cenotes – described in scientific literature as sinkholes or karstic depressions – are made vulnerable by their own physical properties, and that’s why it is so important to protect them.

‘Because they are hollows, there are no soils to retain, transform, or decompose organic or inorganic pollutants. These conditions reflect a high vulnerability to contamination’, she explains.

The report also contains the findings of other research about the cenotes, like that of Dr Ángel Polanco Rodríguez, who detected levels of organochlorine pesticides and insecticides in some cenotes that exceed Mexican and international standards.

Aguilar adds that the waters of the cenotes are interconnected with other vulnerable ecosystems, meaning that when one is affected, they all are. For example, underground waters are linked to wetlands, mangroves, and the petenes mangroves found around the Celestún Lagoon (small islands of trees growing in flooded zones fed by fresh water from springs below), allowing for the growth of specific vegetation that forms a natural barrier to protect the region from the impact of hurricanes or storms.

‘They might appear to be separate ecosystems, but in areas like the [Yucatán] peninsular, which is predominantly made up of karst terrain, there is a full interconnection between rocks, water, soil, and biota [flora and fauna]. At the end of the day, everything that happens inland sooner or later affects other places,’ says Aguilar.

She also mentions botanical studies, in particular one from Dr José Salvador Flores Guido, from the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, which shows the high diversity of fruiting plant species that can occur around the cenotes.

‘What these species do is ensure that there is a wide variety of foods available, which in turn leads to greater diversity in species of fauna,’ the biologist explains.

Studies have also demonstrated the presence of rare or threatened species of bats in the cenotes of Yucatán. Zoologist María Cristina Mac Swiney Gónzalez has identified such species as Chrotopterus auritus and Micronycteris microtis in these areas, both of which are considered under threat in Mexico. The species Eptesicus furinales is found exclusively in cenotes.

Given the diverse species of flora and fauna relying on the cenotes, the report recommends that they are kept in their original state as far as possible, and that this be harnessed for alternative tourism opportunities. ‘This ecotourism would have to be linked with direct management from the communities, because the communities have a biocultural knowledge that it is important to revere, retain, and respect,’ Aguilar concludes.

Sacred spaces

Another of the reports submitted as part of the application relates to the Maya worldview, which centres around the cenotes.

Alberto Velázquez Solis, one of the authors of the anthropological report, says cenotes are considered sacred spaces, as much for the ceremonies that take place there in the present day as for their prehispanic history.

For example, the townspeople of Homún celebrate Jetz Lu’um, a ceremony to keep the cenotes calm and still, whose name literally means ‘to still or placate the earth’. They also hold the agricultural ceremony Ch’a cháak, in which water from “virgin” cenotes is used to pray for rain for the crops.

Velázquez adds that according to prehispanic sources, Chaac, the god of rain, appears inside a cenote. The same oral tradition tells that rain comes when Chaac goes down into the cenotes, collects water in his gourd, and then breaks it open.

‘Cenotes are seen as sacred spaces, each with their own master, which could be an alux or a snake. They are also understood to be the dwelling place of Chaac. In the Maya worldview they are believed to be the entrance to the underworld, and so are highly respected places,’ Velázquez explains.

May Echeverría tells us that he and the other townspeople of Homún were taught that the cenotes were sacred by their grandparents. ‘They told us to enter with care, because we could bring air from the outside with us, which is like bringing in disease.’

Because of all this Maya culture surrounding the cenotes, Kanan Ts’ono’ot is asking the courts to concede guardianship of these spaces to the Maya people, so that they can continue caring for them as they have until now: with respect, moderate use, and continuation of the traditions surrounding them.

‘We want their rights to be recognised because for them the cenotes are not just a ware or a resource, they are an important space, with their own supernatural masters,’ Velázquez concludes.

For now, the collective awaits the final verdict from the courts.

‘We hope the verdict will fall in favour of the community, but if not, we will carry on with the fight. Because this is our livelihood. We are here, fighting for this right.’ May Echeverría promises.