São Paulo. 14 April 2024. A few days ago, Yanomami leader and shaman Davi Kopenawa was received by Pope Francis, head of the Catholic church, in Rome, and Ailton Krenak, author, poet, and environmentalist was elected to the Brazilian Academy of Letters in Rio. Krenak is the first ever Indigenous member of what has until recently been an exclusively white club. During Carnival 2024, Brazil’s greatest expression of popular culture, one of the top Rio samba schools, Salgueiro, chose Indigenous rights and traditions as their theme.

So does this mean that at last, after 500 years of violence and oppression, Indigenous peoples in Brazil are finally being recognized and respected?

Yanomami leader Davi Kopenawa received by Pope Francis at the Vatican. Video: Jornalismo TV Cultura, April 2024.

It seems not. At the same time that Davi and Ailton were being honoured, I listened to university professor, prize-winning author, and museum curator Edson Kayapo describe how he was beaten up and threatened with death by a group of armed men in the south of Bahia, who intercepted the car in which he was travelling with two university researchers, saying, ‘there’s an Indian here’. The unarmed academic was then savagely attacked.

This incident, which Edson Kayapo remembers in every painful detail, happened several years ago, but the violence in the region has continued ever since, with the latest attack in January leaving one person dead and one injured. The scene of these attacks is the south of Bahia state, where the lands of the Pataxo Hã Hã Hã, where the first Portuguese explorers landed in 1500, are being claimed by ranchers who want to sell them off to developers for building resorts along the highly attractive palm-fringed Atlantic coast.

The most recent incident saw 200 armed ranchers and gunmen invade an area which had been reoccupied the day before by a group of Pataxo. They shot and wounded indigenous leader Nailton Muniz and killed his sister Nega Pataxó, a shaman.

Policemen from the Bahian state force were present but did nothing to stop the violence, arrest the attackers or provide medical assistance to the victims, demonstrating the cynical collaboration between law enforcement and lawbreakers. The armed posse had been incited and organized by a social media group called Zero Invasions.

As a demonstration of her importance, Nega Pataxó’s funeral was attended by Sonia Guajajara, the minister for Indigenous Peoples, and other Indigenous leaders. They all spoke of their concern about the dire consequences of the recently approved Marco Temporal, the ‘time limit’ law passed by Congress, in defiance of a Supreme Court decision that it was unconstitutional.

The decision by a Congress dominated by rural and conservative interests not to recognize Indigenous peoples’ ancestral claims to their lands has precipitated a surge of violations of Indigenous rights. Congress decided that any Indigenous community which, on 5 October 1988, was not occupying the land it now claims, is not entitled to it. This decision ignored the fact that many Indigenous nations had been expelled from their territories to make way for the grandiose projects of the military dictatorship, like the Itaipu dam in the south and the Transamazônica or BR174 highways in the Amazon.

Two of Brazil’s largest Indigenous groups, the Yanomami and Munduruku, face a different threat, the silent insidious contamination of their rivers and therefore of their main food source, fish, by the mercury leaked into the water from illegal goldmining operations. A new Fiocruz and ISA study found that in nine Yanomami communities, 94 percent of the population have extremely high levels of contamination. Those living nearest to mining operations have the highest levels. The so-called Minamata disease affects cognitive function and nerve endings. This means that generations of children will be affected by the presence of the toxic metal for years to come.

Later this month, Indigenous peoples from all over Brazil will descend on Brasilia for the 20th Acampamento Terra Livre, an annual mobilization of Indigenous peoples to demand their constitutional rights and denounce injustice.

Received by the Pope, yes. Member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters, yes. A Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, yes. But on a day-to-day basis, still having to fight for their basic rights. When I naively asked Edson Kayapo how long the violence of which he was a target has been going on, he said simply, ‘500 years’.

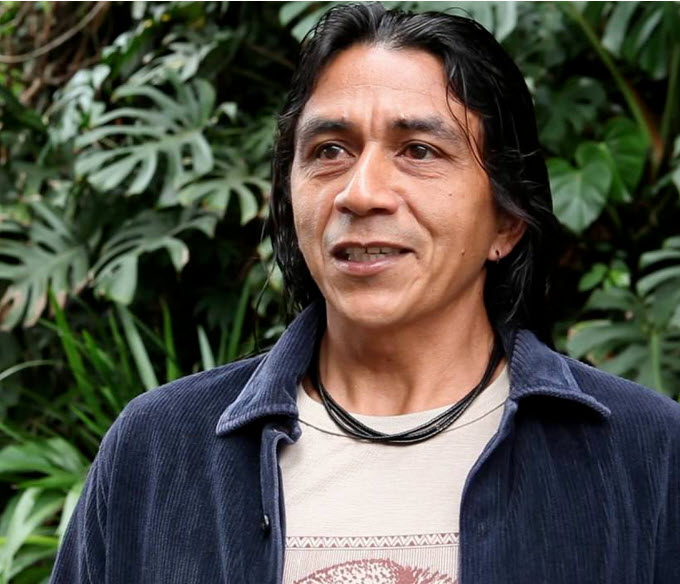

Main image: 2024 02 12, Rio de Janeiro, Ailton Krenak, left, with Davi Kopenawa Yanomami. Photo: Lela Beltráo, Sumaúma