In August this year, the owners of two fincas in the Gualivá province of Cundinamarca, just outside of Bogota, were sent expropriation orders by the national mining agency. An individual named José Elias Yañez Paez plans to install a huge open-pit gravel mine on over 25 hectares of this privately owned land.

At present these farms are mainly used for silvopastoral cattle farming and conservation projects. They are situated in the municipality of San Francisco de Sales, known for its abundant natural springs, waterfalls, and flowing ravines.

Yañez has already received a mining concession from the government and an environmental licence to mine from the local authorities.

Community response

These expropriation orders sounded an alarm in the local community, who responded with a viral video in September 2023 denouncing the situation and highlighting the importance of the area for biodiversity and biological research.

The video, disseminated via WhatsApp and other social media, called on people to support the campaign by alerting the authorities and people who live near to the land in question.

Soon, a community group Gualivá sin Minería (Gualivá Free From Mining) was formed by neighbours in San Francisco, Supatá, La Vega, and other towns in the province, off the back of an existing Acción Ambiental (Environmental Action) WhatsApp community and the Guardianes de Vereda village guardians group.

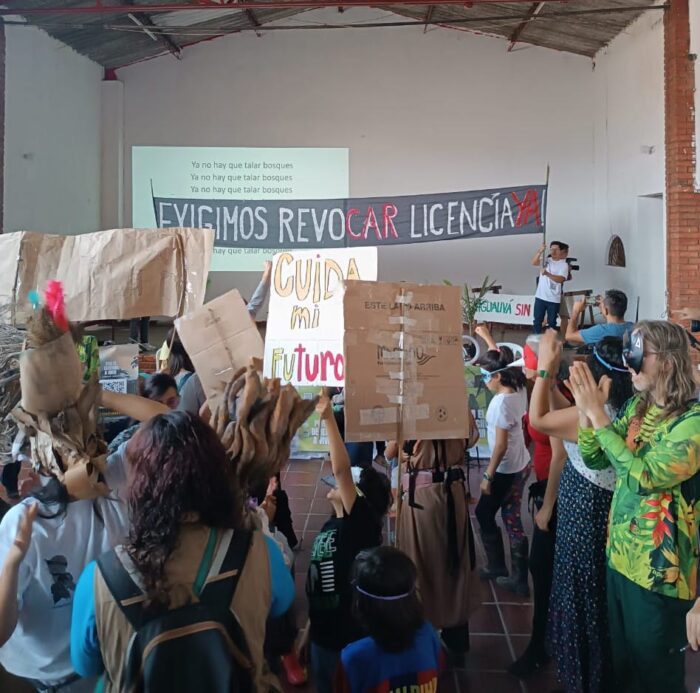

On 18 October, Gualivá Sin Minería organised a historic public meeting in San Francisco. Delegates from the Environment Ministry, the Council of the Rionegro River Basin, the autonomous environmental protection agency (CAR) of Cundinamarca and the San Francisco Mayor’s office attended alongside 200 community members. Locals’ concerns were voiced in powerful speeches and community members of all ages danced to live gaita and drum music wearing masks they had made to represent the animals and plants of the forest.

Meanwhile, the video, with its footage of native forests and bubbling natural springs, reached residents of the whole of the Gualivá region, as well as environmentalists, writers, and policymakers in the capital and even Colombians living in the diaspora. It featured on TV and radio and even in the Colombian Senate.

‘The video wasn’t just posted on Instagram in an aim to gain likes and comments,’ said one of its creators. ‘It was sent personally to people via WhatsApp, who shared it widely. Within minutes it reached authorities and celebrities.’

A corridor of life

The disputed land forms part of a forested escarpment just west of Bogota which suddenly meets the high Eastern Andes. This area is covered by some of the best-preserved High Andean Forests, is a critical hotspot for biodiversity, and has been defined by the Humboldt Institute as one of the few remaining ecological corridors of the region, connecting the national parks of Chingaza and Sumapaz, the Guerrero páramo, the Iguaque Flora and Fauna Sanctuary, and the region’s three Integrated Management Districts.

‘Imagine this corridor like a main road on which seeds are transported, and birds, big cats, and other animals travel, sustaining life in the Sabana de Bogotá and biodiversity on the planet,’ explains Cris Valdivieso, a walking guide based in San Francisco. This critical corridor, known as the escarpe, is at risk of destruction due to mining exploitation.

Enter the miners

In 1998, INGEOMINAS – the government institution which later became the national mining agency – issued mining concession No. 22302 to José Elias Yañez Paez, to exploit 1001 hectares of this area for building materials. That is the equivalent of over 1,400 football fields.

The ‘mining polygon’ spreads all the way the from El Tablazo, a cliff at 3,500 metres in altitude home to a unique páramo ecosystem, to Alto del Vino – where the Agency has previously given concessions for two other open-pit mines, Cerro Cuadrado and La Suiza, both of which have brought environmental degradation and social issues.

Cerro Cuadrado has supposedly been in a ‘state of restoration’ for 23 years, but there has been little progress in closing the terraces or in planting trees to reforest and stabilize the soil. The mine has dried up the stream that used to supply water to inhabitants of the area and flash flooding due to deforestation has destroyed locals’ crops, washed away their fish farms, and caused major closures on the main Bogota-Medellin highway because of dangerous landslides.

Despite these issues, in 2009, Yañez was granted an environmental licence to begin exploiting 25.8 hectares of the escarpment in San Francisco municipality. In Colombia, environmental protection in local areas is the responsibility of regional autonomous corporations, or CARs. Yet it was the CAR of Cundinamarca which granted the environmental licence to decimate this much loved biodiversity hotspot.

Social and environmental disaster

A unique concentration of flora and fauna cohabits here. The mining site itself is home to native trees including Colombian oaks that are hundreds of years old, ancient sapás, cauchos, and endangered pink tunos, not to mention an abundance of endemic orchids.

The Humboldt Institute registered at least 117 bird species living here, including eagles, tángaras, endemic hummingbirds and migratory avifauna. Armadillos, large rodents like agoutis, and red squirrels call this place home, as well as wild cats like tigrillos and the rare jaguarundi, which are both in danger of total extinction.

The CAR recognised the ecological importance of the Escarpe by denominating a 16,500-hectare zone a protected Integrated Management District area (DRMI Macizo El Tablazo). Although this area is supposedly managed and protected by the local authority, the mining polygon, which sits within the coordinates of the area, was explicitly excluded on the grounds that there was a pre-existing mining contract.

The planned mining activity will seriously affect local water sources used by a number of nearby communities. The 25.8-hectare polygon where the CAR has permitted an open-pit gravel mine (and exploration for other minerals) until the year 2037 lies between the villages of Sabaneta, El Peñón, and Pueblo Viejo.

Very few of the residents of Sabaneta have access to piped water, meaning the water they drink, wash with, cook with, and feed their animals and crops with comes from gullies fed by natural springs. The proposed mine would directly affect the Los Limones ravine, the nine natural springs that feed it, and the ‘aquifer recharge zones’ in the upper part of the mountain which cause these springs to surface throughout the region.

Downstream effects

‘It’s important to note that Los Limones meets another ravine within the polygon, creating the larger Quebrada Paloherrado. This meets the Sabaneta River and forms the Río Cañas, which provides water to all the residents of San Francisco de Sales,’ biologist Luis Vargas, who has been working on the case for over a decade, pointed out over WhatsApp.

The Río Cañas in turn flows into the Rionegro River, which provides water to countless towns in Gualivá like Supatá, Pacho, Vergara, La Vega, and Villeta. The Rionegro then feeds the Magdalena, Colombia’s largest and most important river – also a main commercial artery – which flows all the way from the department of Huila in the south of Colombia to the Caribbean Sea in the north, and provides drinking water for 38 million people.

It gets worse: the miner would need to build multiple roads in order to transport and market the materials extracted from this biodiversity hotspot. The main entrance to the proposed mining site is a branch off the Bogota-Medellin highway, which directly passes the local junior school of Sabaneta. Many villagers take their young children to school on foot or by horse. ‘Huge dump trucks carrying tonnes of gravel and earth present a critical threat to these children and families, in terms of road safety, air pollution by sand particulate, noise pollution, and reduced mobility,’ a Gualivá Sin Minería campaigner points out. This pollution of course would affect the whole community and their livelihoods.

Response from the authorities

In response to the video, the CAR Gualivá organised a visit to the site, guided by neighbours and a finca administrator. They were accompanied by a communications expert from the Bogotá office, who took photo and video footage of the site. A response video was later released by the CAR in the same style, claiming that they are frontline guardians of the natural riches of San Francisco and ‘corroborating’ that there was no mine in existence… ‘We will remain vigilant to any threat of illegal activity,’ they state.

The owner of a finca backing the mining polygon bit back: ‘They are not looking after the Escarpe. They haven’t done their job. They have distorted the narrative of our communications about their incompetence and the imminence of a legal gravel mine. They talk about an illegal mine but no one said there was one. We are talking about a mine that’s ‘legal’, since it was signed off in spurious fashion by this very institution who calls itself a guardian of the area… They haven’t done their job, but we hope that they will do so in future thanks to pressure from the community.’

National and international support

From the outset, the local community has pushed back against the licences, which they believe were granted upon fallacies. The environmental licence No. 0626 granted by the CAR Cundinamarca states that there are no surface water streams or rivers, nor groundwaters for water recharge in the polygon. It doesn’t recognize the geological fragility of the escarpment – which features three geological faults within the mining polygon – nor its ancestral native forests and endemic fauna which are key to the local ecosystem and to science.

In 2016, members of the community filed an Acción Popular. This is a collective legal action brought by a group of claimants that have been affected by an occurrence in the same way. Despite pushback, the Acción Popular remains on the desk of magistrate Claudia Elizabeth Lozzi Moreno at the Administrative Court in San Francisco, where it has sat for seven years, unanswered.

A longtime supporter of the campaign against the mine and a villager in the municipio, lawyer Diego Méndez Perilla has just been elected as a town councillor of San Francisco. He has vowed to continue to support the causes that his environmental supporters stand for and told LAB that his first mission is to propose a municipal regulation highlighting that 1) the land is question is of protected forest vocation and its industrial use is prohibited by the San Francisco planning office, and 2) the Mining Code states that mining cannot be carried out on protected soil.

The national press has also taken interest in the community’s struggle, with Semana, El Espectador, Pulzo and TV.Net publishing the story.

A petition launched by the community on the 4 October, calling for the mining contract and the environmental licence to be revoked, now has over 10,000 signatures, including one from President Gustavo Petro’s account.

Following a visit to the site in October, engineers and geologists from the CAR Gualivá put together a report highlighting the risks of mining in this area and suggesting the licence could be taken away for a number of reasons, including the lack of activity over a period of more than five years. The director of the CAR Gualivá, after three weeks, also signed the motion. However, for it to become active, the general director of the CAR Cundinamarca must sign. He is looking for excuses to avoid doing so. Two months remain before the newly elected provincial leader takes office in January. Residents are terrified that another Cerro Cuadrado will decimate this ancient forest.

Despite the support of public figures, pressure from the community, a few institutional workers, and the many Colombians in solidarity, nothing has been done to stop the miners. In fact, vans from the national mining agency have been spotted trying to enter the property and further expropriation orders and offers to buy the land have been received by the owners.

From their territory, the community sends out an urgent call to international organisations to help them to achieve a definitive solution.

‘We must see both the 25.8-hectare environmental licence to mine and the 1001-hectare mining contract REVOKED, to save the critical water sources that feed tens of thousands of us, as well as the many species in this area – migratory, endemic, animal, plant, fungi.’

The international NGO Yes to Life No to Mining has received the community’s request for support but a local conservationist tells LAB, ‘we still need further support to help the community defending the Escarpe to legally advance with our demands.’

‘We extend an invitation to the international media to help us disseminate this information. You can help by signing our petition, sharing the video, and posting about our struggles. Please get in contact if you’d like to receive information or audiovisual materials to bring our case to international media.’