Seven months ago, the residents of Santa María Chi, a precinct of the Yucatán city of Mérida in southern Mexico with a small population of 480 people, started to fall ill with rhinitis, acute pharyngitis, sinusitis, bronchitis, and stomach problems.

These health complications have been caused by pollution and fires on the 178-hectare San Gerardo pig farm, which is leased through sharecropping contracts to the pork farming giant, Kekén. The farm sits right within the community, just metres from residents’ homes.

On 3 April 2023, neighbours from Santa María Chi, Sitpach, X-cuyum, Yaxkukul, and Cholul began to post on Facebook groups about the strong smell permeating their communities.

Wilberth Nahuat, the elected commissioner of Santa María Chi, told Memorias de Nómada in an interview that he contacted the San Gerardo farm directly to enquire whether the fire was on their property, given the owners of the farm tended to burn swine. They denied it.

Days later, on 13 May, the fire spread to the farm’s vast pig sheds and the fire brigade had to be called out to tend to the fire. When the fire truck arrived and the firefighters entered the property to quell the flames, residents realised that the smoke they’d been breathing for more than a month was in fact emanating from Kekén.

‘They had been calling the fire brigade for a week. Pig excrement is full of gasses so, if it catches fire, it will continue to release smoke if it’s not put out. Once we found out that what they were burning was pig excrement, we understood that it was these toxic fumes that were causing respiratory problems among the villagers,’ Nahuat explained.

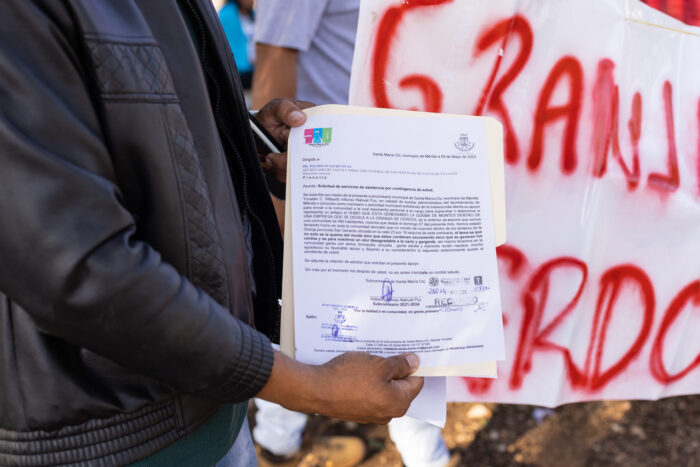

Locals tried to speak with the farm administrators but ‘they left us with questions on our lips and turned their backs on us,’ explained Nahuat. So locals built a camp outside of the farm gates in protest, demanding dialogue with the administrators and handing them a series of complaints.

The Loret de Mola family owns the farm which has supposedly been shut down. There is a sign pinned up on the gates stating its closure, but there is no formal closure order or notice. Those interviewed assured us that the farm opens and closes periodically. No one from the farm has responded to requests from Memorias de Nómada. On the contrary, a representative from the pig farming group reported Wilderth Nahuat Puc for ‘depriving the liberty’ of farm workers and ‘obstructing access’ to the farm by way of the protests. According to the report, their demonstration impeded farm workers from leaving the site, despite the fact the protests took place in front of the entrance, allowing workers to leave through the exit on the other side of the farm.

The restriction order against Nahuat Puc states that the local commissioner can’t come within 300 metres of the farm’s registered land. However, the farm lies 100 metres from his house and its lands surround the entire village, practically enclosing it.

‘The conflict around the farm has been ongoing for years. We’ve been dealing with this situation for 30 years but it’s reached a point where we’ve been forced to demonstrate. 20 years ago it was nothing compared to how it is now. Before, they had a few small sheds but now they have 73 warehouses holding 600 pigs each. You can see how many more pigs they have by the number of trucks coming in and out. Before you’d see a truck coming through with 20 swine, now the trucks are stuffed, moving hundreds of hogs every day.’

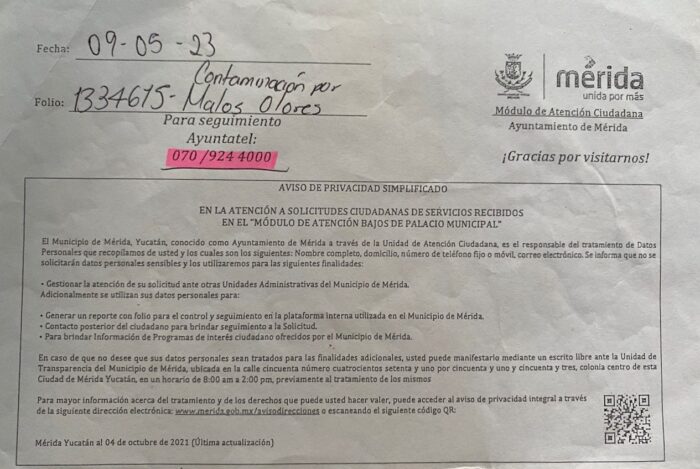

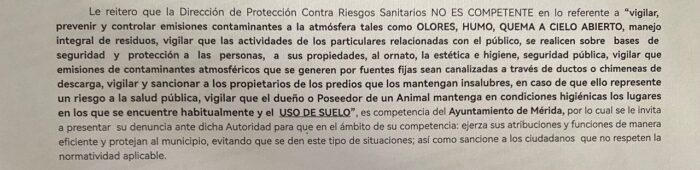

On 9 May 2023, Wilberth Nahuat sent an official letter to the Yucatán Health Secretary (SSY) explaining the grave health situation villagers were facing. The SSY responded that they weren’t competent to address the situation and that the commissioner should report to Mérida Town Council – who also denied that villagers’ health issues were the responsibility of their municipal authority. Villagers are now filing complaints with the Mexican federal government’s environmental protection agency.

‘They want to eliminate the waste generated by all of those pigs but they don’t have the means, so they burn it,’ one of the interviewees told us.

On the day of the interview, the Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources, a federal agent, came to the village. Locals assumed she had come in response to the complaints and felt let down when they found out she’d actually come to check on some communal lands. She didn’t even address their demands.

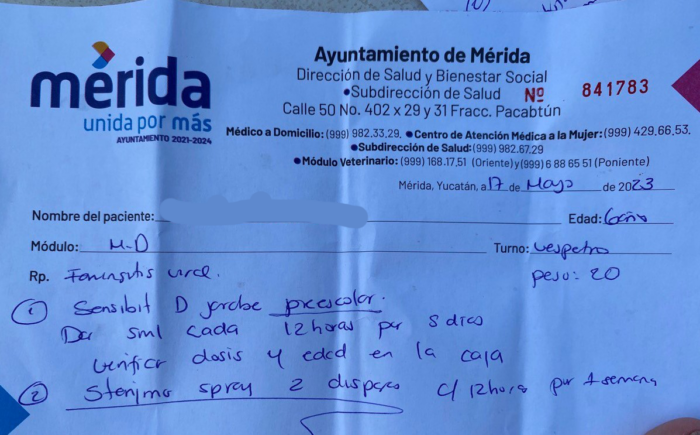

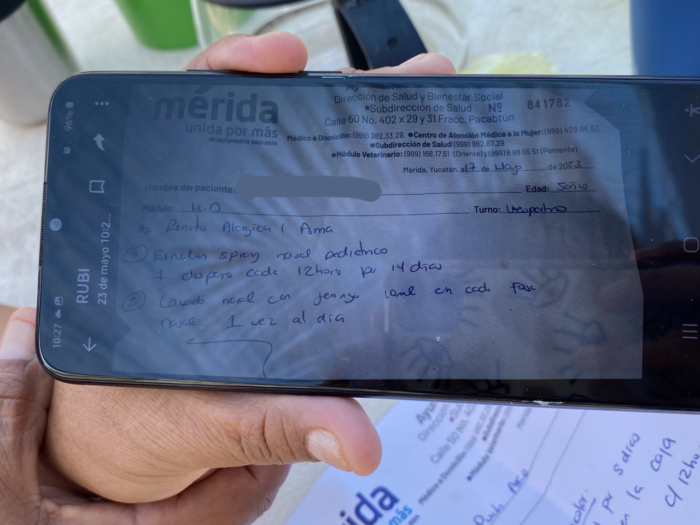

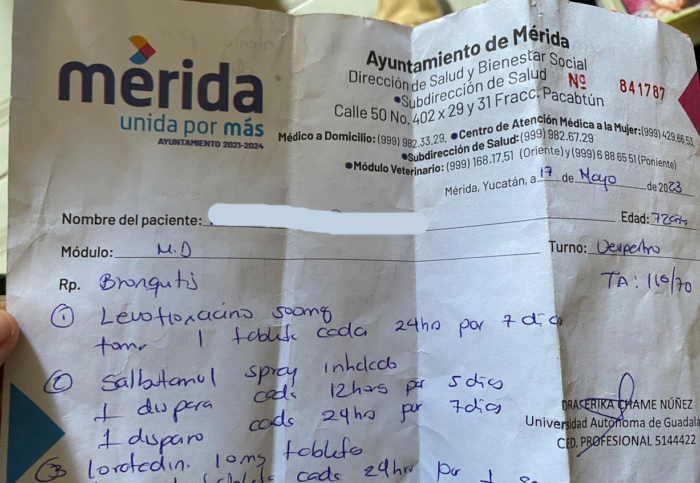

Although Nahuat is kept at home by the restriction order against him, the majority of the local population is organised and sustains their protest. At the camp, residents show their prescriptions from the doctor, someone shares the medical study of a 10-month-old baby with rhinitis who had to be sent to live elsewhere because staying at home would risk their health, another informs that elderly locals have spent all their money on medicine which hasn’t cured their bronchitis, rhinitis, or acute pharyngitis.

Doctors tell the residents of Santa María Chi to avoid strong cleaning products and oven smoke, but there’s nothing they can do about the farm storing more than 40,000 pigs and burning their excrement right in front of residents’ homes.

The site of the protest camp is the home of various Santa María Chi neighbours. It is also a driveway passed by five to 10 trucks of pigs every day in the early hours and throughout the day. The nuisance they’ve had to put up with for 30 years has only increased with the recent fires.

‘Respiratory diseases are one thing, but what about water pollution? In a few years our water will be poison. We won’t be able to use it for washing, bathing, or watering our plants,’ another interviewee laments. ‘Look at the colour of the water. Before we used to grow crops, but we haven’t been able to grow anything recently because Kekén killed the crops. We used to grow corn, squash, watermelon. Now you plant something and it dies. It’s a tree cemetery… it’s such a sad sight to behold.’

This article was originally published by Memorias de Nómada, a cultural journalism magazine who share the work of artists, defenders, and inspiring people in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico.