Latin Americans are one of the fastest growing migrant and ethnic groups in London and the wider United Kingdom, yet they remain one of the most invisible. This has been reflected in research and advocacy aiming to raise the profile of the population, including work by the Coalition of Latin Americans in the UK (CLAUK) and the #StandUptoInvisibility campaign developed by Let’s Talk Latinx, a group of young people with Latin American roots in the UK.

However, despite ongoing research, there has been limited analysis of the British 2021 census. Instead, most population estimates rely on the most recent comprehensive analysis, Towards Visibility, a report by myself, a professor at King’s College London, and civil servant Diego Bunge, from 2016. This estimate combined the 2011 census and additional data on the second generation and those with irregular status. These data showed that there were 250,000 Latin Americans in the UK and 145,000 in London. It is clearly time for an update on the size of this diverse set of communities, as well as a revision of the terminology used to refer to them.

What does British Latinx mean? And does it matter?

Addressing first the terminologies, while many and arguably a majority in the UK still use ‘Latin American’ or ‘Latino/a’ to refer to people and communities, there has been an increase in the use of ‘Latinx’. This is rooted in part in decolonial debates in Latin America amid calls to refer to the Americas as Abya Yala, a Kuna language Indigenous term that challenges the violence of colonialism. It also links to confrontations around United States imperialism over the continent, the erasure of Indigenous identity in referring to people from Latin America as ‘Hispanic’, and heteropatriarchal attitudes that enforce gender binaries of Latino/a.

A range of alternatives have emerged including Latin@ (the at sign signifying both an ‘a’ and an ‘o’, but remaining binary), Latine (the ‘e’ replacing the masculine/feminine binary of o/a suffixes), and Latinx. Although Latinx has gained increasing traction beyond the US to denote a specific diasporic set of experiences and identities, it remains highly contested, especially among older generations.

In the UK, there has been some movement towards using Latinx or British Latinx since the 2010s. Its use has been most widespread among three groups. First, among some second and third generations who want to differentiate themselves from those born in Latin America while honouring their diasporic Latin American heritage. Second, by feminists and those wishing to promote greater gender fluidity in terminologies. Third, among an emerging artistic and literary movement in the UK exemplified by the social media hashtag #LatinxArtUK and the first ever anthology of British Latinx writing, Un Nuevo Sol (edited by Nathalie Teitler and Nii Ayikwei Parkes, 2019) where the writers chose to use the term.

Patria Román-Velázquez and Jessica Retis in their book on diverse diasporic Latin American communities living in the UK, Narratives of Migration, Relocation and Belonging, use Latin American for people (whether born in the continent or not) and Latinx for diasporic cultural practices and identities. However, there is no uniform acceptance of the term.

While Dani, 30, who is non-binary and from Uruguay states: ‘For me, Latinx sounds more universal’, others are less convinced. For example, 34-year-old and UK-based Valeria from Ecuador rejects it in favour of ‘Latine’: ‘Latinx is an inclusive term in terms of being gender neutral. However, I feel more comfortable with the [term] ‘Latine’ as the X makes it feel Anglicised. We, in Spanish, traditionally use -e as gender neutral [suffix], so I prefer Latine.’

Similarly, Juan who is 25, also living in the UK and from Colombia notes: ‘Growing up in Latin America I never heard the term LatinX and it was only recently, when I became more connected to the Latin community in the UK, that I heard it. I’m still unsure about how I feel about it. I really welcome the fact that it’s trying to be more inclusive … but I still have a sense that it’s something that has been imposed on the language from outside. I don’t use the term myself, but I respect anyone who does.’

Others use it in some situations and not in others such as Aline, 27, from Brazil, who notes when asked if she uses Latinx: ‘Great question. Short answer. Sometimes. Long answer: if I am talking about a collective identity then yes, but if I am simply answering “who/what are you/where from?” I would just say my nationality.’

This suggests that Latinx is not as commonly used in everyday language as might be expected. It also reflects the situation in the United States where it has been argued that Latinx tends to be used among elites in higher education, especially by academics and among young activists and LQBTQI+ groups, with recent polls showing a three to four percent favour for the term. In light of controversy, Latin American needs to be retained, but Latinx and Latine should also be respected as legitimate for those who wish to use it.

Also important to note are multiple differences among Latin Americans. One of the key lines of differentiation is among Brazilians and Spanish-speaking Latin Americans. While somewhat dated, No Longer Invisible (2011) noted how in a 2010 survey with over 1,000 London-based migrants born in the Latin American continent, 70 percent of Spanish-speakers identified as ‘Latin American’, but only 44 percent of Brazilians did, with the majority preferring to identify as Brazilian only. Other axes of differentiation are strong among specific Spanish-speaking nationalities. These include differences between political exiles and economic migrants, between those who migrated directly from Latin America and those who moved to other countries – usually Spain, Portugal and Italy – prior to moving to London, coined ‘Onward Latin Americans’ or OLAs. This final group comprised more than a third of all those arriving in 2010.

Ethnic and racial differences are also important across all generations, as noted by Alex, who is non-binary and of Bolivian Aymara, Irish, and English heritage: ‘I don’t [use Latinx] cos it doesn’t feel very closely orientated to my mum’s Aymara roots, feels like I get lumped in with whitinos too and considering the history of colonialism on Abya Yala it just don’t feel right! But I do use it when talking to people who aren’t familiar with the continent, so they can understand… but with people who are more familiar, I prefer the term andino/x. That reflects our land, our mountains, our heritage… more so than Latinx, I feel…This doesn’t mean I wouldn’t use it if it was included on the census though, just would be great if there was subsections under Latin American which differentiated between ppl of European descent, indigenous descent, African descent and ppl who are a mixture of the above.’

The Latin American population in London is growing

While the historical emergence of Latin Americans moving to London dates back to the 18th century, more recent movements have seen exiles from Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Colombia moving to the British capital in the 1970s and 1980s, and subsequent migration to work – mainly in low-paid manual roles – among Colombians, Ecuadorians, Peruvians, Bolivians, and Brazilians. Their arrival brought the establishment of civil society organisations, media outlets, and a range of cafés, shops, restaurants, and events.

Our 2001 and 2011 analyses focused only on country of birth data from the census and data excludes those not included in the census such as those with irregular status (estimated to include 19 percent of Latin Americans in 2011 or those of Latin American heritage born in the UK).

Latin American heritage was not possible to ascertain from the census as there was no appropriate ethnic categorisation option, despite repeated campaigns since before the 2011 census. This has however been acknowledged by several local boroughs: Southwark, Lambeth, Hackney, and Islington, and the Greater London Authority. The countries included in the 2001 and 2011 analysis excluded all those in Central and South America where English is the official language, but included Cuba and the Dominican Republic. In 2021, I have included Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, and Belize in my analysis to reflect the importance of conceiving of the Americas as the pre-colonial Indigenous Abya Yala.

Bearing these caveats in mind, the growth of the Latin American population in the UK has been extraordinary. Between 2001 and 2021, there has been a 406 percent increase in London and a 395 percent increase in England and Wales, based on census data.

In terms of the breakdown by nationality in the city, Brazilians are the largest group (55,790), followed by Colombians (27,848), Ecuadorians (15,756), and Guyanese (10,717). There are also sizeable populations of Argentinians, Venezuelans, and Bolivians.

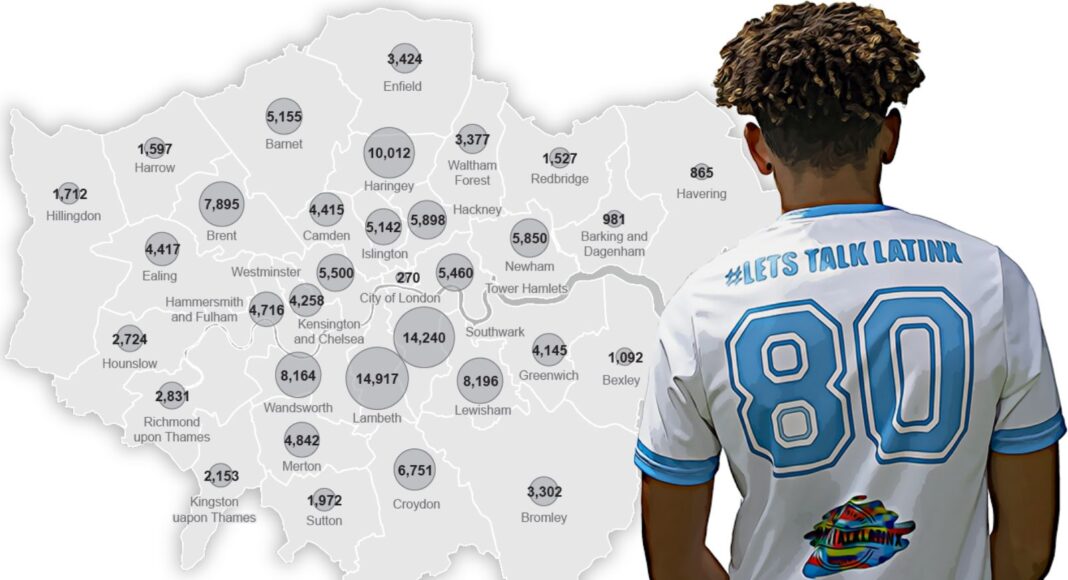

Around two-thirds of Latin Americans in London live in inner city boroughs, especially in Lambeth, Southwark, Haringey, Lewisham, and Wandsworth (Figure 1). In several London boroughs such as Lambeth and Southwark, Latin Americans represent the largest ethnic migrant group (14,917 of 122,555 in Lambeth; 14,240 of 132,304 in Southwark). In both of these boroughs, there are large numbers of people born in Portugal (7,012), Italy (5,675), and Spain (4,344), many of whom are likely to be of Latin American heritage whose parents had moved to these countries prior to the UK. However, it is difficult to deconstruct this without an ethnic categorisation and because many of these will have passports from these countries regardless of their heritage in Latin America.

Distribution of Latin American-born population in London in 2021. Source: ONS 2021 census

What are British Latinidades?

In light of the exceptional growth of Latin American/x communities in London (and the UK), it is important to consider British Latinidad. While the concept of Latinidad has been developed in the US to denote the cultures and identities of those sharing a Latin American heritage, it has also been critiqued as being exclusionary of Black and Indigenous people born in Abya Yala, reminiscent of the exclusionary, colonial term ‘Hispanic’. Nonetheless, a form of British Latinidad or Latinidades has emerged.

First defined in academia by Román-Velásquez and Retis in 2021 as denoting multiple forms of post-colonial belonging, British Latinidad reflects hybrid identities that are negotiated for political means. In other words, it acknowledges deep divisions, as noted above, but also shared experiences and the need to acknowledge their presence in the UK and in London as an ethnic group.

For some, they will always be Latin American and Latinidad will have limited meaning, yet for others, a specifically British sense of multiple Latinidades that captures how they have carved out a life in the UK and in London is essential in their self-determination. For this latter group, some are suggesting being referred to as British Latin American, Latinx, Latino/a, or Latine as a way of ensuring they play a role within the UK’s multicultural society on an equal footing with other Black and Minority Ethnic Groups to ensure their visibility and as a form of resistance. This will of course take time, but demographic growth (not to mention a lively artistic and cultural scene) may make this population impossible to ignore sooner rather than later.

Cathy McIlwaine would like to thank the Coalition of Latin Americans in the UK (CLAUK) (Jacobo Belilty), Empower LATAM UK (Cesar Rodriguez Valido), Latin Elephant (Natalia Perez), and Renata Peppl for their assistance in writing this blog. She is also grateful to Steven Bernard for producing the map in Figure 1.