In a world where weddings are postponed, birthday parties are held via video chat and we have to be encouraged to spend, rather than to save, in order to support local businesses, it is unsurprising that the Colombian Flower Exporters Association reported dramatic losses: estimated sales for Mother’s Day were 40 per cent lower than that of the previous year.

In 2019, an estimated $1.5 billion worth of flowers was exported from Colombia, with the USA accounting for over 77 per cent of that total. The cut-flower industry is a significant contributor to the Colombian economy due to the low labour costs, meaning that flowers have become one of the country’s fastest growing exports.

However, along with low labour costs come the poor working conditions associated with casual labour. Most non-contractual workers in the flower industry are not unionised; one of the few independent unions, The National Organization of Colombian Floriculture Workers (ONOF), has made little headway in improving working conditions. Any attempts by unions to improve working conditions are neutralised by the widespread use of ‘collective pacts’, largely unknown in the West, described as ‘collective agreements negotiated and signed by non-union worker representative and employers [which] offer benefits to non-unionised workers’.

The chasm between the two Colombias is vividly illustrated on the outskirts of Bogotá. The pot-holed dirt tracks that you would expect to take you to flower farms, also lead you to the wrought iron gates of some of the country’s highest performing international private schools, because it is far cheaper to build there than in the centre of the city.

One such establishment, and one that to some extent recognised inequality in Colombia, is a co-educational school for children aged 4-18, that initiated ‘The Foundation’ – a social inclusion programme, located next to its own sports field, which was designed to bridge this chasm.

The programme was offered to local parents, the majority of whom were employed in the flower industry, whose children were given free nursery classes and school meals. The parents, who earned on average $200 monthly from casual labour on flower farms, could not even dream of paying the tuition fees of this international school, whose main student body comes from well-heeled Colombian families.

However, this international and progressive school believed it was its duty to benefit the community around it, commenting on its website that it inspires its own students ‘to make a positive difference in the world around them’. Students were also encouraged to fundraise and support The Foundation by supplying it with school supplies, some benefactors donating books, games and materials.

While the motives for creating the nursery were admirable, thanks to the variability of casual labour on flower farms, the children at The Foundation often attended irregularly, some not coming to school for days at a time when parents found no work and could care for the child themselves. Moreover, in the last year, The Foundation has been closed down, and all evidence of its previous existence erased from the school’s website.

According to a member of staff, the school was ‘able to integrate one boy into Year 1 on a full scholarship’. However, the school administrators, when asked about status of the nursery, maintained that ‘its students are fully absorbed into classes in the school, not as a separate group’, describing the change as ‘better integration for them’. Yet even if these two groups are really integrated, the contrast in economic background of the pupils is undeniable.

Colombia’s Gini index of rating of 0.54 makes it the second most unequal country in Latin America after Honduras. The gap between those that are able to attend a private international school with tuition fees that could buy you a small car every year, and those that could attend a subsidised nursery in their grounds, is growing wider due to Covid-19.

Covid-19 arrives

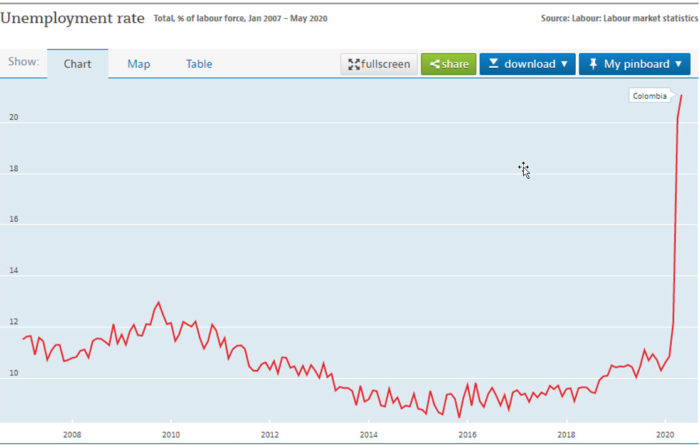

Then the Covid-19 pandemic arrived. Now President Duque faces an unemployment level of 21.09 per cent, doubled since January. A former pupil of a Bogotá international private school comments that Colombians ‘don’t believe him [Duque], they lack confidence in him, and he fails to convey a message of safety’. In the developed welfare states of the North, the pandemic has forced many of the employed to live within their means, cut expenses and put aside luxuries, while the self-employed and those without regular incomes have been protected to some extent by government support schemes. However, borderline dysfunctional states such as Colombia can only dream of this option.

An International Baccalaureate Coordinator at a private school in Cali adds that new social distancing regulations, restricting individuals to their homes on even or uneven dates depending on the last digit of their national identity number, has ‘brought concerns that students may not enrol’ as schools limit daily attendance to 30 per cent capacity. Additionally, ‘In Colombia, [only] 62 per cent of students report having a computer they could use for schoolwork, which is lower than the OECD average [89 per cent]’. This clearly exacerbates the problems surrounding online teaching, even for the relatively privileged.

Meanwhile, the flower workers’ organisation ONOF has signalled its frustration with the government’s handling of the pandemic, noting that ‘although in the decree issued by the National Government, floriculture does not belong to a production sector deemed to be “of basic necessity and supply”, it has continued to work normally’. And, if the industry is working, so must its workers, whatever the personal risk. ‘The unions have promised that for anyone returning to work to stimulate the economy, they will commit to supply antibacterial gel, soap and masks’.

Yet, if the 111,000 Colombians who work directly in the cut-flower industry, and the 94,000 others employed indirectly, could be offered better working standards, and the industry fully regulated and organised by the state, then one significant sector of the Colombian economy might be able to recover from the ravages of Covid-19.