This article was first published here in Portuguese by Agência Pública and translated to English by Matty Rose for LAB.

You can also subscribe to the biweekly Agência Pública newsletter in English here.

Prosecutors, attorneys and police working on conflict between palm oil giant Brasil BioFuels and traditional communities are being harassed in the courts

At around 8pm in the Tomé-Açu municipality of the state of Pará, northern Brazil, Adenísio dos Santos Portilho, an Indigenous Turiwara man, started to head out of town by car, accompanied by three friends. After leaving the village of Braço Grande, located in the Turé-Mariquita Indigenous Territory, behind them, they stopped shortly before boarding the boat that would take them across the Acará River. When they got back in the car, Clebson Barra Portilho took Adenísio’s place at the wheel. Just minutes later, Clebson was hit in the head by a series of gunshots and died on the spot. Adenísio, the original driver, had been the intended target.

In the same attack, which happened on September 24, 2022, Cleozo dos Santos, 35, also an Indigenous Turiwara man, received bullet wounds to the head and right shoulder. He survived the attack but suffered life-changing injuries. Adenísio himself was hit five times in his legs. Just one of those traveling in the car escaped unscathed. On the same night as the attack, hours later, the cultural centre of Braço Grande was set on fire. Brazil’s federal police have been investigating the two incidents, but as yet no one has been arrested.

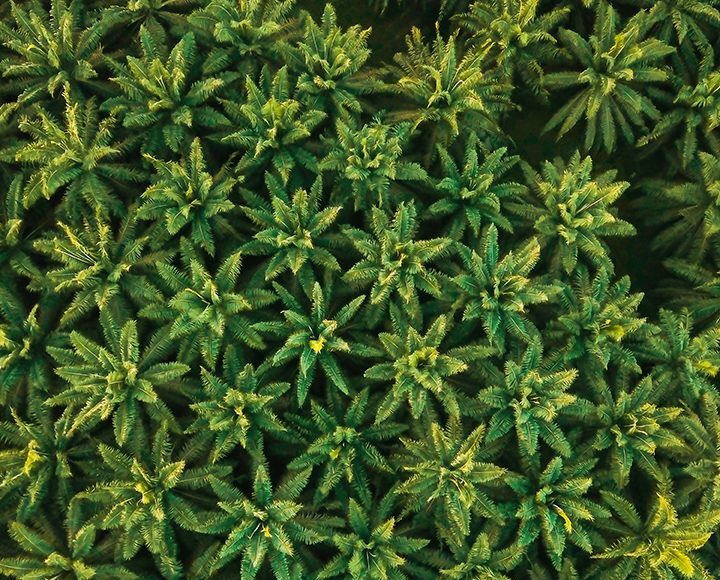

This is the first murder of an Indigenous person in the Tomé-Açu region since Brasil BioFuels (BBF), a Brazilian company that produces biofuel from palm oil, started operating in the region. Ever since the company arrived, confrontations between Indigenous locals and security guards working for the company, as well as reports of threats and restrictions of movement through the area have happened on an almost daily-basis.

The violence and tense atmosphere are being heightened by another factor: legal harassment. Although the company states on its website that it holds ‘continuous dialogue with the communities living in the region’, documents and testimonies obtained by Agência Pública point to a kind of judicial crusade being coordinated by Brasil BioFuels. Members of traditional communities have been the target of lawsuits launched by the company, as well as those who have investigated the conflict and defended the rights of these communities, such as prosecutors from the Public Prosecutor’s Office of the State of Pará (MPPA) and the Federal Public Ministry, and police officers.

According to Emério Costa, one of the public prosecutors from the MPPA who has been working on the cases in the region, BBF has filed a significant number of lawsuits and retaliatory accusations in order to disrupt and slow down the progress of other lawsuits in which the company itself is being investigated. BBF’s palm plantations lie on public land which is claimed by Indigenous and Quilombola communities, as reported by an Agência Pública investigation in August 2022.

Adenísio, the intended target of the fatal shooting in September last year, told Agência Pública that he has been harassed by the company for his efforts speaking out against the advance of oil palm plantations over Tembé and Turiwara Indigenous land. He has been living in hiding since 2021 because of the threats he has faced. ‘For us, it’s a matter of life and death, we’re asking for help from every public body,’ he told Agência Pública via telephone.

In November, a 28-year-old Indigenous man, two others and a minor claimed they had been beaten on a remote highway by security guards working for BBF. The attack allegedly took place just hours after dozens of Indigenous and Quilombola community members gathered on a farm, belonging to BBF but intruding onto Indigenous territory, to protest against a recent court ruling in favor of the company. By the end of the day, the ruling had been suspended.

Agência Pública had access to a video which shows men dressed in light green uniforms while a number of Indigenous people are lying on the ground with their hands on their head and a scuffle takes place in the background. Responding to the video, BBF did not confirm that the violent incident was committed by its employees and stated that the Indigenous people were “faking it and creating a scene for it to be recorded in an attempt to incriminate the company”.

The overlapping of oil palm plantations with land claimed by traditional communities has been an issue in the region since before BBF arrived on the scene, officially in 2008 and then effectively in 2020 when the company bought the plantations run by another company. The previous plantation owner was Biopalma/Vale, a joint venture between Biopalma da Amazônia and the Brazilian multinational corporation Vale. Under the previous ownership, 27,000 people were affected by the land conflicts, according to data from the Environmental Justice Atlas. The change in ownership of the plantations has seen conflicts over land become more heated, both physically and judicially, in the rural parts of the Acará and Tomé-Açú municipalities, which are home to 55,000 and 64,000 people, respectively.

A wave of lawsuits

Data from the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT), a body that monitors and registers cases of conflicts in the Brazilian countryside, revealed that in 2022 there were nine nine criminal incidents against Indigenous people and Quilombolas in Acará and Tomé-Açu involving BBF. In addition to the case involving Adenísio, described above, another three attempted murders were recorded by the Pastoral Land Commission between July 2022 and the end of January. The narrative offered by BBF to the courts and the police is that the company is the victim of criminal acts carried out by communities in the region.

The company’s version of the situation has been recorded in 134 police reports at Civil Police stations in Tomé-Açu and Acará over the course of 2021. Between January and October 2022, another 154 reports were registered, an average of one report every two days.

‘The wave of police reports filed against community leaders appears to be an attempt to criminalize social movements in the region,’ Emério Costa, the public prosecutor, said.

The data system of the Department for Public Security of the State of Pará does not record whether those targeted in the police reports are from traditional communities. BBF itself, however, has admitted to filing more than 650 police reports aimed against fellow local community members in the period since it set up operations in the region.

Among the crimes alleged by BBF are the theft of timber, tractors and oil palm fruits; threats made against drivers and a bus belonging to an outsourcing company contracted by BBF to provide transport for workers in rural regions; trespassing on private property and arson.

Names of local Indigenous leaders feature among those most frequently cited in the police reports and lawsuits filed by the company. Many of them are the targets of several lawsuits at once.

Ahead of an upcoming hearing, the Indigenous cacique Edvaldo de Souza reiterated that the accusations made against him and others are unfounded. ‘They don’t just accuse one individual, but several local leaders at once. They say “the Indigenous showed up carrying weapons, with knives, scythes, rifles and pistols”, but the company never mentions that they have weapons, that they walk around armed and confront us,’ de Souza argued.

With respect to the use of firearms by private security guards, BBF stated that the company contracts security services because of the nature of its work, and that it is the target of constant crimes.

Paulo Nailzo Portilho, another Indigenous leader, said that he was under investigation for the alleged theft of two tractors and for trespassing on BBF’s property. He denies the charges. ‘Our community took what was already ours [the land], then they tried to accuse us of invading their land, of stealing their machinery,’ he said.

Portilho was referring to the portion of the Indigenous Territory that had been taken over for palm oil production. No buffer zone exists between the land held by the company and the land held by traditional communities, meaning that oil palms are planted on the boundary of the communal land of traditional communities and, in several places, intrude across this line.

BBF, meanwhile, stated that the company stopped harvesting 25,000 tonnes of oil palm fruit over a three month period because of the alleged trespassing and harvesting carried out by the traditional communities. Indigenous leaders have not denied that some of the fruit has been sold, and have justified this by saying that it is necessary for their own subsistence.

‘We’re in a situation of great need here. Because of the oil palms, we no longer have anything to hunt, and the products that they discarded into the streams have killed the fish, so we had to sell the fruit in order to have money to get something to eat,’ said cacique Paulo Nailzo.

The products that Nailzo referred to are the agrochemicals used on the plantations, as well as tibórnia, a residue from the oil palm itself that, according to reports, is dumped in the rivers. In 2021, the Federal Public Ministry applied to the courts for an investigation to ascertain whether the health of neighboring Indigenous communities had been damaged by the use of agrochemicals on BBF’s plantations. The request was denied.

The sale of the company’s oil palm fruit is not the only way that local communities have mobilized against BBF. Local community members have also worked with national and international NGOs to record information, in addition to the occupation of spaces owned by the company. All the actions taken by the communities are known to the MPPA and the state’s Public Defender’s Office.

Legal harassment to hinder investigations

While it attempted to criminalize members of traditional communities, BBF has also rounded on the public bodies that defend the collective rights of these communities and investigate the company’s actions.

In 2022, the company filed a legal complaint questioning the actions of prosecutors from the MPPA and an attorney from the Federal Public Ministry.

The complaint was made to the National Council of the Public Ministry (CNMP) and resulted in the opening of an internal investigation, which was conducted confidentially and later shelved. One of BBF’s complaints filed against the MPPA seeks to separate crimes against the company’s assets from the land conflict in the region, claiming that the cases are independent and asking the judiciary to investigate and judge the cases as criminal ones, rather than as relating to land disputes.

As far as the prosecutors are concerned, however, the land dispute is the core of the issue and, therefore, BBF’s allegations of theft and threats should be considered are part of the land dispute, and judged in the Agrarian Court, rather than a criminal court.

According to Emério Costa, the prosecutor who has been working on conflicts involving BBF, their actions are based on Brazil’s Constitution and follow the judiciary body’s own guidelines.

Costa explained that cases such as these involve aspects from several fields of law, such as environmental, agrarian, territorial and community laws. ‘Taking proper account of such complexity is not down to the behavior of Prosecutor A or Prosecutor B, but of following what is written in legislation,’ he concluded.

In March 2022, the prohibition of traditional communities’ right to come and go was the subject of a complaint by the MPPA, in which it defended the constitutional right to ‘collective mobility’. The MPPA’s complaint was questioned by BBF before the body’s Inspector General Office, with the company stating in its complaint that the MPPA commits ‘repeated omissions, combined with mistaken decisions’. The company asked the MPPA’s Inspector General to guide and supervise the ‘functional activities and the conduct of the members of the Public Ministry.’

According to Ione Missae da Silva Nakamura, a prosecutor who was also the target of complaints by BBF, only for the case to be shelved, the company’s strategy does not hold up in court. ‘We don’t deal with disputes here on the basis of violence and criminalization. This will mainly be resolved as a land and agrarian issue, of who really owns the land. It seems to me that they [the BBF] don’t want to get into this discussion,’ Nakamura said.

According to Costa, the BBF’s insistent accusations against employees are designed to intimidate. ‘These procedures are used when the arguments of those being investigated are unfounded. Knowing that they will likely lose the lawsuit, the company has used strategies to hinder the investigative work.’ Costa said.

Agência Pública tried to gain full access to the complaints made by BBF to the MPPA Inspector General’s Office, however they were told that they were confidential.

As well as the judiciary, the police force has also been targeted by BBF. Agência Pública has received information that complaints were made against police officers in Tomé-Açú, where three officers were replaced in 2022, partly due to requests for removal to other cities.

Police officers have reported a lack of time to adequately carry out their work, citing the pressure to file police reports on the conflict, which has been an issue since the local police’s activities involve a number of other issues beyond the territorial conflict between BBF and traditional communities.

When questioned about their complaints against public servants from the aforementioned bodies, BBF responded that it ‘will not comment on the subject, since it is an internal matter for the company and because it does not comment on its legal strategy towards judicial bodies.’ The full note sent by the company can be read here.

Overlapping land claims

BBF is involved in land disputes affecting more than one traditionally occupied territory. The territory of the Alto Acará History Quilombo Residents and Farmers Association (Amarqualta) has had its titles partially granted by the Palmares Foundation, with its territory measuring 12,400 hectares. The case has remained open with the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), the federal authorities responsible for the administration of public land in Brazil, since 2009. This is partly because of sluggishness on the part of the Brazilian state, with the granting of titles to traditional territories in decline since the Temer government, ending in the lowest number of approvals during the Bolsonaro government. Another reason is because of a request made by Amarqualta for recognition of a larger territorial claim, measuring 22,000 hectares, home to all of the families that have lived in the region for generations.

Video showing BBF security guards, apparently firing on Quilombo residents at Amarqualta in the Vale do Açara, Pará, on 16 April 2023. Video: Amazónia Real — video added by LAB

The Turiwara Indigenous people have also claimed a separate part of the Turé-Mariquita Indigenous Territory, which has yet to be demarcated. A process is already underway with FUNAI, Brazil’s National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples, whose technical teams have already made reconnaissance visits to the indigenous part of the region.

BBF, meanwhile, has been fighting in court for restitution of several of their farms. According to the company, 5,366 hectares they own have been ‘invaded’ by local communities.

On just one property, the Vera Cruz farm, there are dozens of areas overlapping with traditionally occupied land spread across the 41,200 hectares that it declared in the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) system in Pará, amounting to 36 per cent of the total area of the farm. In a statement, the company denied any overlap with traditionally occupied areas.

According to Elielson Pereira da Silva, a researcher from the Federal University of Pará who looks at the bioeconomy of palm oil, the cycle of violence wrought by palm oil is advancing across an Amazonian frontier area that has already been devastated by illegal logging.

‘In Tomé-Açu, the situation is no different from other cities across the state of Pará. These cities are important logging centers, then cattle ranching moves in, before moving on to other areas, making way for oil palm plantations. This large plantation model is alive and well, and violent, armed land grabbing is the key point for its expansion,’ Silva said.

Palm oil is the pride of Pará

The state of Pará prides itself in being the market leader of Brazil’s palm oil industry, on top of other products such as cocoa and açaí. The production of palm oil, promoted by the government, has continued to grow in both extent and production, year on year. If in parts of the judiciary there is a fight to protect the collective rights of traditional communities, others from the executive and legislative branches of power have taken the side of the palm oil producers.

Among them is the lawyer who represents BBF in criminal cases, and who has previously occupied a number of roles in the Pará state government. One of those responsible for the strategy of legal harassment, Luiz Fernandes Rocha, was previously the head of the state’s security department, the state secretary for environment and sustainability, and president of advisory board in defense of the Amazon rainforest. Fernandes Rocha’s experience and resumé suggest that he has a good command of the issues in the cases that BBF faces and files.

On the ground in Tomé-Açu, the local mayor, Carlos Antônio Vieira, shows little appetite for resolving the conflict raging in the municipality under his control. This is because he himself has been charged in the courts with the illegal occupation of Quilombola territories.

Everyone cited in this report was contacted for comment by Agência Pública, by telephone or by email. The lawyer and former government minister for the state of Pará, Luiz Fernandes Rocha, and the mayor of Tomé-Açu, Carlos Vieira, had not responded to these requests by the time of publication.