Since 2020, more than 400 farms located inside indigenous territories have been granted titles thanks to a new ruling from the National Indian Foundation (Funai)

This article was first published here in Portuguese by Agência Pública on 19 June 2022 and translated to English by Matty Rose for Latin America Bureau.

You can also subscribe to the biweekly Agência Pública newsletter in English here.

On April, 24, 2020, Marcelo Xavier, the president of Brazil’s National Indian Foundation, known as Funai, and Nabhan Garcia, the Brazilian government’s special secretary for territorial issues, excitedly made an announcement. Xavier and Garcia, two of the most influential agribusiness lobbyists in the Jair Bolsonaro administration, celebrated the passing of Funai’s Normative Ruling No.9 (IN 09), which would allow farms located inside unratified Indigenous Territories to be certified and registered in the Federal Land Management System (SIGEF).

In practice, the introduction of the new ruling brought an end to the “so-called SIGEF dirty list” – as Nabhan Garcia described it at the time – and gave the green light for farmers to occupy Indigenous lands across the country. More than two years on from the passing of the new ruling, an investigation by Agência Pública has revealed that the Bolsonaro government has certified 239,000 hectares of farmland inside these areas of Indigenous Territories – an area of land twice the size of the municipal area of Rio de Janeiro.

Unratified Indigenous Territories are those which are still waiting upon the publication of a presidential decree in their favor – the final phase in the demarcation process before the territory is definitively registered – and include both territories which are still under review and those which have already been declared or delineated. After more than three years in office, Bolsonaro has not ratified a single Indigenous Territory. Furthermore, when the former judge Sérgio Moro was in charge of the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, which Funai is a part of, the government halted 17 demarcation processes that were almost complete.

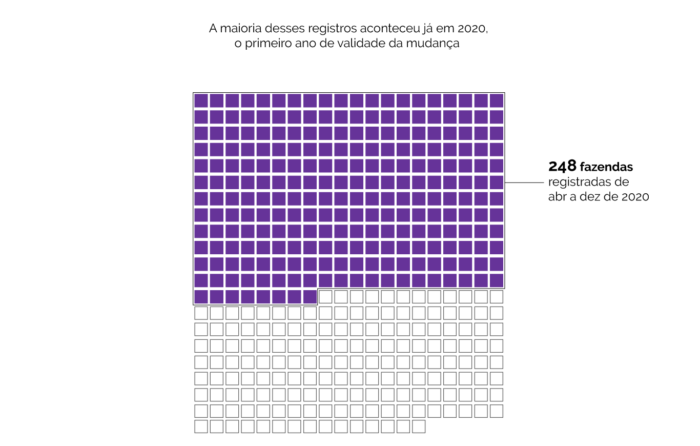

The majority of the certifications took place in 2020, when 124,000 hectares spread across more than 240 farms inside Indigenous Territories were certified between April and December of that year.

The data shows that this phenomenon is not only restricted to cases where farms spill across the boundaries and over into stretches of Indigenous Territories, since the majority of the properties that have been certified – 210 – are located 100% within the confines of the Indigenous Territories.

We want demarcation, we need land to live

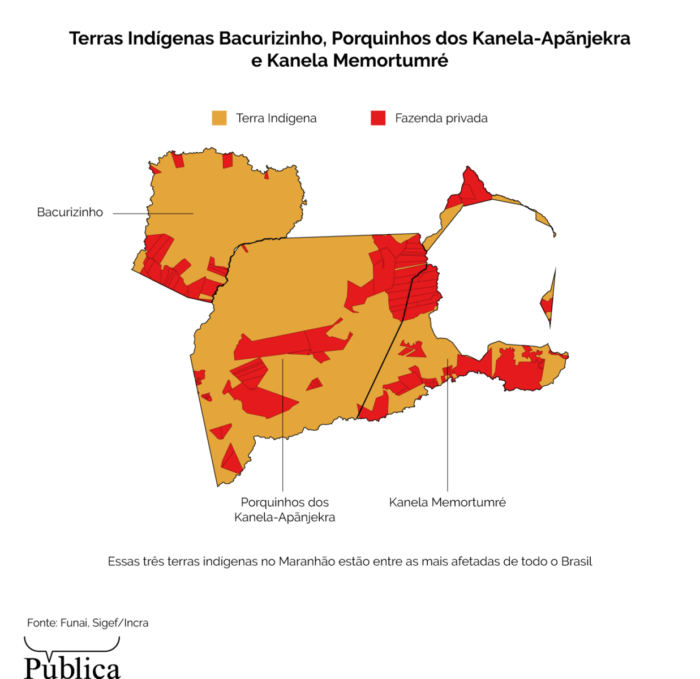

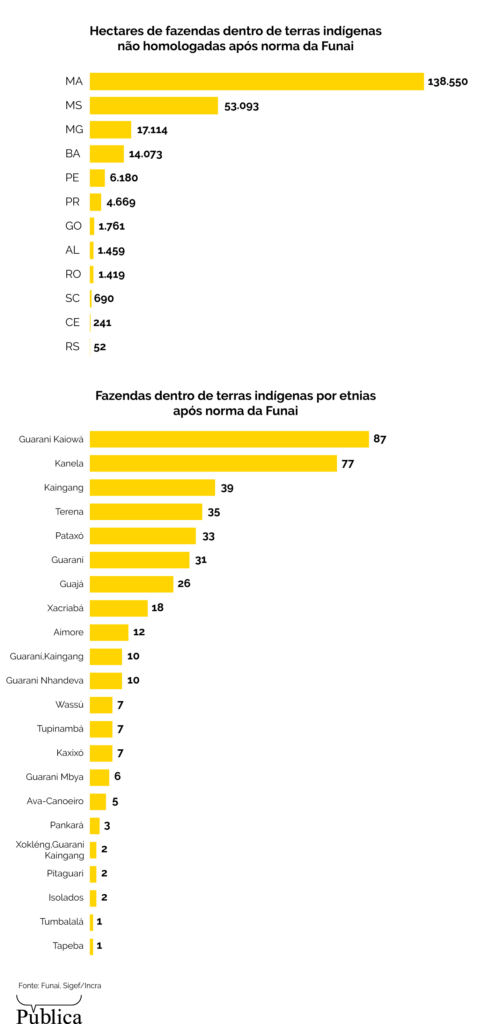

The majority of the Indigenous Territories which have been affected by the Funai ruling are located in the state of Maranhão, in the northeast of Brazil, where more than 138,000 hectares of land have been certified as private properties in the government’s land management system.

More than 20 ethnic groups live in the areas where farm titles have been certified. The group hardest hit by the ruling have been the Canela people, who saw 117,000 hectares of farmland demarcated inside their territory. The Canela people have been fighting for years for the ratification of two of their territories in the state of Maranhão, the Kanela/Memortumré Indigenous Territory and the Kanela-Apãnjekra’s Porquinhos Indigenous Territory. The seriousness of the situation facing the Canela people was already highlighted by Agência Pública in a report released about a month after Funai’s Normative Ruling No.9 was announced.

Both the Memortumré territory and the Apãnjekra territory have been partially demarcated by the government, however studies which aim to expand the limits of the Indigenous Territories have been brought to a halt – and it is in these areas that the Funai ruling has allowed the certification of farm titles to take place. In February this year, a preliminary decision by the Maranhão state court ruled that the application of Normative Ruling No.9 ought to be suspended in the state. Five months later, however, and the land that was certified in the wake of the ruling remains the same.

Agência Pública’s Map of Conflict illustrates how the area where the two Indigenous Territories are located have seen some of the highest levels of conflict in the state in recent years, something which has been experienced first-hand by Paulo Thugran Canela, an Indigenous man from the Apãnjekra people. He claimed that the attacks in the region had worsened in recent times.

“The smoke [from fires] is coming into indigenous land more and more, a lot of children are suffering from coughs, [and] are falling ill because of it. Deforestation keeps increasing, hunters are arriving [on our land], loggers are arriving [too]. In the past, the land was well protected and respected. What’s happening now is concerning for us,” said Thugran Canela, who works as a teacher in the Indigenous Territory.

According to Carloman Koganon Canela, leader of the Kanela/Memortumré Indigenous Territory, invasions by farmers, hunters, and loggers are commonplace. Indigenous peoples on the territory have also had to deal with an irregular road that passes through the middle of their village, which has already led to deaths caused by road traffic incidents in the area.

“We don’t want conflict, we want to live as we always have done, on our own land. The community is concerned by what is happening. We want demarcation [to take place], we need land to live,” said Koganon Canela.

At the end of June this year, Carloman and other Indigenous members of his village delivered a petition to the judge of the 3rd Federal Civil Court in Maranhão, calling for the annulment of Funai’s normative instruction. In the document detailing the request, they drew attention to the large number of land certifications made on their territory, as well as highlighting how the destruction caused by the use of agrotoxins in the region had scared off animals that they would usually hunt and had jeopardized their traditional way of life.

After the Canela people, the second most affected group by Funai’s Normative Ruling No.9 are the Guarani-Kaiowá, who live in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, in the central-west region of Brazil. More than 26,000 hectares across six different Indigenous Territories in the state that are occupied by the Gaurani-Kaiowá have been lost to private farms, according to government registers.

Certification rushed through

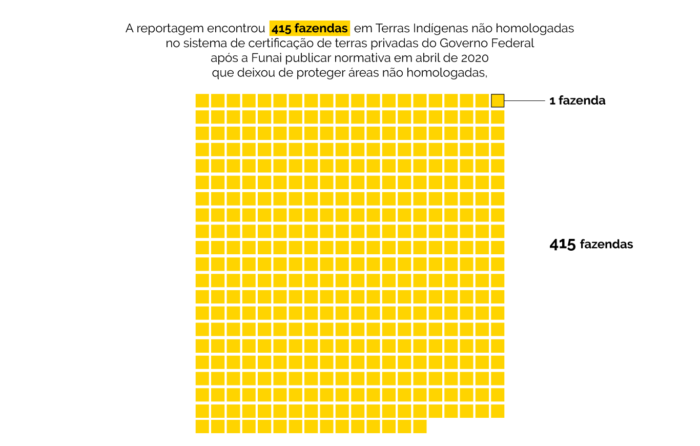

All in all, tracts of land inside unratified Indigenous Territories from a total of 415 farms were certified. This even included cases of latifúndios, or large-scale rural estates, such as the Boa Esperença II farm, the third largest property to benefit from the measure.

Thanks to the Funai ruling, on January 25, 2021, the Bolsonaro administration recognized the Boa Esperança II farm, which lies entirely within the boundaries of the Porquinhos Indigenous Territory, belonging to the Canela people. The recognition of this piece of farmland was almost instant, occurring on the same day as the request for recognition was submitted to SIGEF, the government’s land management system.The government has been dragging its feet on the regularization of the Porquinhos Indigenous Territory for more than 20 years. Local authorities in the municipalities of Barra do Corda, Fernando Falcão, Formosa da Serra Negra and Mirador – which cover the same area as the Porquinhos Indigenous Territory – have challenged the demarcation of the territory in the courts since 2010. The Indigenous Territory lies right in the middle of the ever expanding front of soya plantation and cultivation in Brazil, in the region known as the Matopiba, an area of the Cerrado biome equivalent in size to France and England put together.

According to the federal land management system, the rancher Geraldo Verschoor is supposedly the sole owner of the Boa Esperança II estate, officially located in the municipality of Fernando Falcão, in the state of Maranhão. However, databases consulted by Agência Pública from the federal body INCRA – who are responsible for the administration of public land in Brazil – point to the existence of additional owners, among them, one of the heirs of the old Batavo company, a giant of the dairy industry founded in the southern Brazilian state of Paraná over a century ago.

Suspicions surrounding the ownership of the Boa Esperança II farm have also intensified due to an ongoing case in the Agrarian Court of Maranhão.

As well as Geraldo Verschoor, another 17 people appear as defendants in this case, all of them with links to the property. Some of them take turns at the helm of Frísia, one of the “richest agricultural cooperatives in Paraná“, created and managed by the heirs of the Batavo company.Another of the defendants in the same case is Renato João de Castro Greidanus, ex-president of Batavo and one of those in charge of the Frísia cooperative according to the Federal Revenue’s current records.

The complete list of defendants also includes the Dutch rice farmer Auke Dijkstra, and the State Deputy Plauto Miró Guimarães Filho, a Bolsonaro ally who was one of the president’s earliest backers in the 2018 elections. Auke Dijkstra, Plauto Miró Guimarães Filho and Renato João de Castro Greidanus are not listed as responsible for Boa Esperança II in the government’s current land management system, but are listed as owners of the property in the National Rural Registration System, the government’s former self-declared land database, managed by INCRA.

Agência Pública contacted those named above for comment, asking about their relationship with the Boa Esperança II farm that lies on the territory of the Kanela Indigenous people, however no response was received before the publication of this report. In the event of those contacted responding to the requests for comment, this article will be updated.

Federal Public Ministry halted certification processes in 13 states

Shortly after the publication of the Funai ruling, members of Brazil’s Federal Public Ministry from across the country started to launch efforts against the measure.

For Ricardo Pael, a prosecutor from the Federal Public Ministry of Mato Grosso, a state in the central-west region of Brazil, and the first to bring a public civil action aimed at overturning the Funai ruling, the measure is based on “a restrictive view of indigenous territorial rights with respect to their original nature.”

“[The measure] is a very clear choice by Funai to defend and prioritize the rights of the non-Indians, in detriment to Indigenous peoples. If a rural [farmer’s] using the same hypotheses, it would be fine, because it is a defense of the rural owners’ right to property. It’s not something that you would expect to read or hear from a public body that defends the rights of indigenous peoples,” Pael explained.

By the time of publication of this report, at least 29 court cases in 15 states across Brazil had been launched against the Normative Ruling No.9.

The measure was overturned, whether by court rulings or preliminary injunctions, in 13 Brazilian states, including seven in the region known as the Legal Amazon: Acre, Amazonas, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia and Roraima.

On top of these, the Brazilian Judiciary also ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Bahia, Santa Catarina, Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso do Sul and São Paulo. In some states, the rulings are only effective in certain districts, such is the case for rulings regarding the municipality of Passo Fundo, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, and in Janaúba, in the state of Mato Grosso, which only affected the municipalities covered by the districts in question.

Despite the judicial victories suspending the measure, the Funai ruling has had concrete effects on indigenous territories, according to the MPF attorney Pael.

“There has been a significant increase in the number of invasions of indigenous lands, this being the most palpable and most immediate harm caused to indigenous peoples. [The ruling] ended up greatly incentivizing land invasions and the increase of the illegal exploitation [of the land], both in terms of logging and mining,” he explained.

According to Pael, those taking part in illegal land invasions in the state of Mato Grosso have even used the Funai ruling as a basis for the defense of their actions.

In the eyes of Rafael Modesto, legal advisor to the Indigenous Missionary Council, Funai’s normative ruling is part of a “range of actions by the federal government that put wind in the sails of illegal miners, farmers, loggers and other invaders.”

Among the other measures cited by Modesto is the Normative Ruling 01/2021, by Funai and Ibama, the environmental regulator, which authorized “partnerships” between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples, and Resolution 04/2021, which restricted Indigenous people’s ability to self-declare their Indigeneity, until it was suspended by the Supreme Federal Court.

Other measures taken by Funai have towed the same line, such as the substitution of anthropologists working on demarcation cases, and the failure to carry out necessary protective measures on unratified Indigenous Territories – something which was also overturned by the Supreme Federal Court.

*The report is part of the Emergência Climática [Climate Emergency] series of special reports, which investigates the socio-environmental violations that result from carbon-emitting activities – ranging from cattle raising to the production of energy. Full coverage can be found on the project’s website.