In this fifth post in the CAMeNA blog, about the unique history archive in Mexico, Cornelia Gräbner describes an extraordinary set of documents which capture the most intense and dangerous phase of repression in El Salvador, leading up to the 1992 Peace Accords.

Historian and activist María Luz Casal has conscientiously collected and documented liberation struggles and pan-American solidarity in Central America. Her collection of documents was one of the first to be donated to the CAMeNA. It bears witness to the commitment and dedication, to courage and persistence in the face of adversities, and to the refusal to let oneself be overpowered by any opponent, whoever they may be.

‘Getting involved in the Central American organisations was like an injection of vitality. These were movements in the midst of an uprising, movements in which the people participated. I was gobsmacked by the demonstrations in El Salvador. People from all sectors of society joined in. The army threatened to kill pretty much everyone, but the people were there, and they carried on, and on. There was an effervescence, a political consciousness that astounded us. They revitalized us, they brought us back to life.’

María Luz Casal radiates warmth and enthusiasm when she speaks of the El Salvadorean movements that she and her husband, Carlos Leoncio Balerini, started to support in the late 1970s. ‘The context, the environment, held such a spirit of struggle, such an effervescence, that you couldn´t just sit there and watch’, she says.

The pair of experienced activists and militants started to support the El Salvadorean group Resistencia Nacional in the late 1970s. Previously, they had witnessed and survived the civilian-military dictatorship’s attempt to exterminate all forms of dissent in their native Argentina, had narrowly escaped Argentina for a short time in exile in Mexico, and had supported the Nicaraguan Frente Sandinista para la Liberacion Nacional (FSLN) in logistics, military training, and documentation.

Then, after a thorough reflection on ideological consistency and strategic integrity, they decided to dedicate their efforts to Fuerzas Armadas de la Resistencia Nacional (Armed Forces of National Resistance), which eventually participated in the umbrella organisation FMLN (Farabundo Marti Liberacion Nacional).

El Salvador is popularly known as the ‘Pulgarcito’, the ‘Tom Thumb’ of Latin America, evoking the fairy tale character of a small and disadvantaged boy who wins the day through perseverance and intelligence. El Salvador is tiny in terms of territory, about the same size as Wales.

At the time when María Luz and Carlos Leoncio decided to intertwine their fate with that of the Salvadoreans in struggle, a national oligarchy made up of landowners and the army defended its dominance over an increasingly rebellious population by any means necessary.

Most of El Salvador’s population lived in the countryside, and the economy was predominantly agricultural, relying on plantation crops like coffee and cotton. Almost all the land belonged to a handful of families who exploited the workers, repressed any attempt at self-organisation, and discriminated against indigenous peoples and peasants.

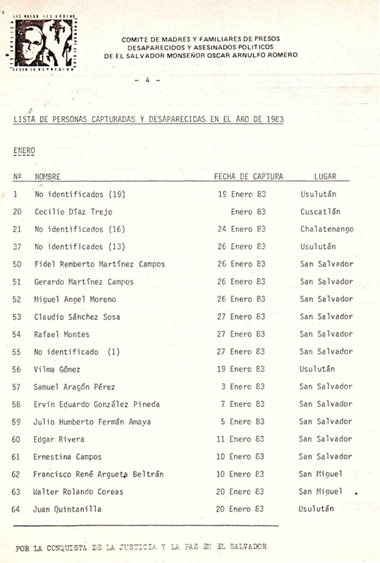

Despite this, land workers got organized, and in the cities trade unionists and university students rebelled against a classist, oppressive, unjust system. For over a decade, some had opted for armed resistance. Whatever the means that people chose for, any dissent or attempt at organisation was met with savage, unrestrained violence by death squads, many of which operated out of the army. The army, in turn, received massive amounts of funding and training from the United States.

Faced with a repression that aimed at eradicating (as distinct to, for example, domesticating) those who dissented and resisted, many movements decided that the only way forward was an armed uprising to liberate the country’s territory step by step.

Active in resistance

Initially, María Luz works in documentation and propaganda and Carlos Leoncio, in military training. Then, they are assigned to running a safe house and to support RN´s logistics operations in Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

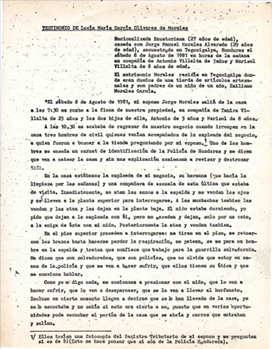

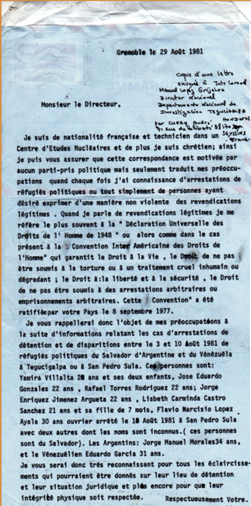

On 8 August 1981, unidentified armed men raid the house and detain Carlos Leoncio and all the Salvadoreans who are staying there. María Luz is beaten and threatened. Eventually she manages to escape with their 1-year-old son Emiliano, and asks for political asylum in the Mexican Embassy. Once she gets to Mexico, she continues to work in solidarity with the FMLN, while also searching for her husband.

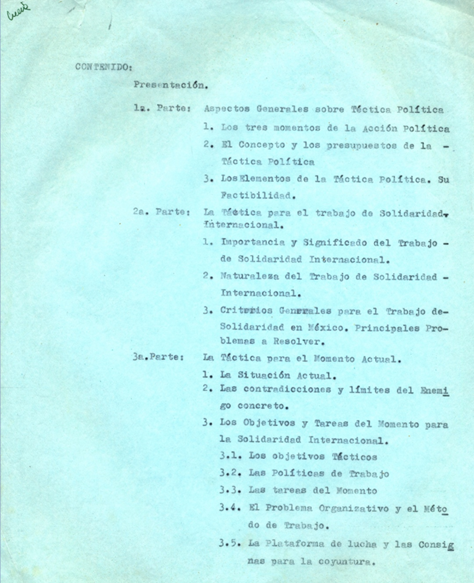

Resistencia Nacional are aware that they owe support to those of their own who have become victims of persecution, as well as to the civilians and the activists who have become victims of persecution and violence by the army. They know that if they want to offer a viable alternative to the status quo in El Salvador, they cannot concentrate on armed struggle alone, and that they have to accept that many people and organisations of good will are civilian and wish to keep a distance from armed struggle.

RN start forming working groups and networks, many of them in exile. Among them is the so-called ‘Humanitarian Area’ in Mexico, which Mariá Luz coordinates. Resistencia Nacional works together with organisations such as the Committee of Mothers, the independent news agency Agencia por la Paz, the Committee of Political Prisoners, and the Human Rights Commission of El Salvador.

‘It was tough’, María Luz remembers, ‘Many of the compañeras [from the Committee of Mothers] weren’t necessarily, or only, family members. They themselves had been tortured, raped, victimized in horrific ways. One of the compañeras from the Committee of Mothers had lost more than thirty family members to assassination.’

They arrange interviews with the press, TV, press conferences, run a news bulletin, and organize speaker tours for the Committee of Mothers to the U.S. and Canada. They work with a network of US priests who offer El Salvadorean refugees sanctuary in their churches, and set up an on-the-ground method for raising awareness: ‘The community members of each church organized gatherings at their home, where the refugees would offer their testimony, and each household who attended then committed to organizing another gathering to which they would invite ten more households.

‘It was a way of reaching out to the people of the United States from below, so that they would hear directly from those affected what was done in El Salvador with the millions of dollars that were sent there daily by the US government, how this money was spent, how people were getting raped, tortured, cut into pieces, pregnant women had their wombs cut open and the foetuses ripped out – it was horrific. This had much more impact than an article in the press.’

In Mexico, those working in the Humanitarian Area involve whoever they can, in a relationship of solidarity and while respecting other organisations’ autonomy. Trade Unions support by letting activists eat for free in their dining halls, and by offering their assembly halls for events. Protestant communities and churches provide office space, as well as indoor and outdoor event spaces. Cultural centres offer space and facilities for music and arts events, and informational exhibitions.

‘We organized a vigil with an umbrella organisation of Protestant churches’, remembers María Luz, ‘At each full hour a different activity started, a film, music, a testimony. We ended at 7am with a church service in which a pastor from each of the denominations participated.’ In addition to these efforts by Resistencia Nacional, other organisations join together in the Committee for Solidarity with El Salvador, also building international solidarity with those fighting and surviving.

The price of commitment

María Luz and Carlos Leoncio had decided to intertwine their lives with those organized in Resistencia Nacional, and the price they paid is horrific. María Luz never found Carlos Leoncio, and raised Emiliano on her own. Now, decades later, their son researches secret operations of the Argentinian security services in Central America and specifically, El Salvador.

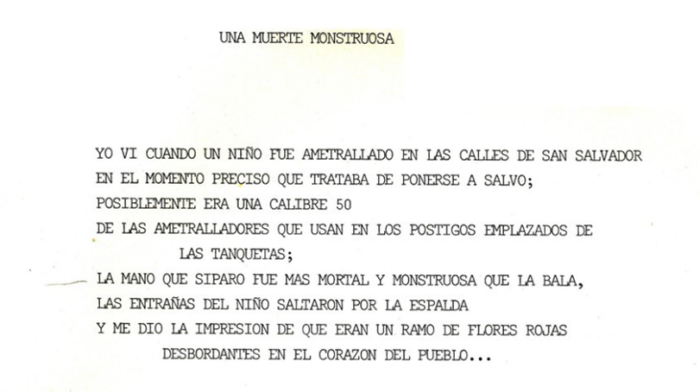

A passionate historian, María Luz countered attempts at exterminating the efforts of her comrades, and all traces of them. She kept and stored documents that testified to what they did and how they thought. When people passed through her house in Mexico, they brought articles, letters, notes, drawings, poems.

María Luz kept everything: ‘In the heat of war what people least want is to collect papers’, she said, ‘But I’m a historian, and I wasn´t in the midst of the fighting. If I’d been at the front it might not have occurred to me to collect all these documents. But I was here, in Mexico. And because I was involved in setting up Documentation Centres in Costa Rica and Nicaragua I know the value of a document.’

She also knew what it is like to lose them. When she was working at a documentation centre in Managua, she transcribed a multitude of documents from microfilms that she projected on the walls: ‘Some of these were tremendously sharp analytical works. And there were articles, poems, short stories. I even transcribed Roque Dalton’s [poetry] book Un libro rojo para Lenin, which was eventually published in Nicaragua.’ She still has her transcription of the manuscript; but everything she did not keep and conserve herself, is now lost or dispersed.

The Salvadoreans brought María Luz and Carlos Leoncio back to life after the shattering repression they experienced in Argentina. When the Salvadoreans themselves were subjected to a repression that aimed at exterminating their lives and their efforts and delete any trace or memory of them, María Luz conserved testimonies and traces.

Eventually, she donated the documents to CAMeNA so that anyone who wishes can learn about the perseverance and dedication of those committed to liberation and justice for the ‘Pulgarcito’ of Latin America.

Now, in 2022 more than 40 years later, María Luz still marvels: ‘One day the National Guard, who had the reputation of being very brutal, marched into a place where the Committee of Mothers were on hunger strike. And a tiny, skinny lady stands up in front of a soldier, pushes her chest out and says: ‘Shoot! Kill me, come on, go ahead!’ The soldier had gone for the only father amongst the hunger strikers, the only man, and she’d put herself between the two. I asked myself, what cloth are these people cut from? How is it possible that just like this, without weapons, she stands up to a guy who is twice her height, armed to the teeth, who is there to kill her – and she´s that calm?’

Main image: 28 May 2021, San Salvador, members of the Co-Madres took part in an ecumenical mass to mark the Week of the Disappeared Prisoner. Co-Madres (the Comité de Madres y Familiares de Detenidos y Desaparecidos y Asesinados Políticos) is the same organization that was established in 1977, at the height of the repression in El Salvador, under the protective umbrella of the Archdiocese of Santiago, and whose courage María Luz celebrates.