A bright, warm morning in Mexico City. The sun shines onto the café space in front of the Libreria Rosario Castellanos in the neighbourhood La Condesa. Writer Paco Ignacio Taibo II does not need to order his Coca Cola; the waiter only politely asks for confirmation. We sit outdoors not only because the weather is nice, but because Paco Ignacio chain-smokes.

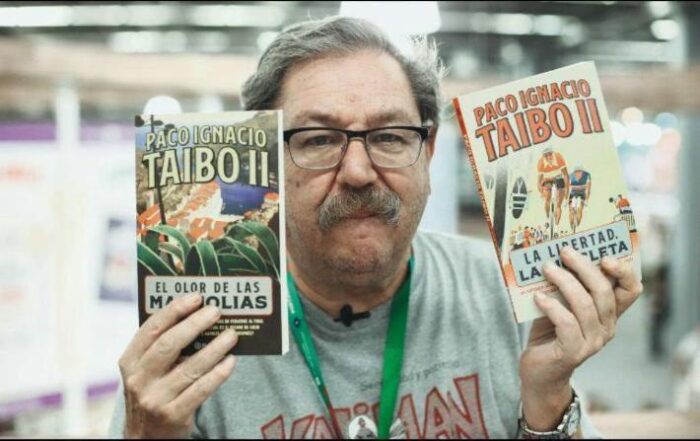

Paco is famous for his crime fiction and his popular historical writing including biographies of el Che Guevara and Pancho Villa, narratives like Patria about social and political movements, and the anecdotal books about those agents of history who never became famous, like Arcangeles or La libertad.

Taibo’s books draw on painstaking and wide-ranging documentary research, and Taibo has now donated three of his collections to the CAMeNA archive: those he assembled for the biographies on el Che and on Pancho Villa, and those he assembled on armed liberal movements for Patria. ‘My house was turning into a living library’, he remembers, ‘You could never find anything.’

Taibo wanted to ensure that the material he had collected would be freely available freely to the public. He had attended events and spoken at the CAMeNA. He felt that staff were doing an excellent job, and that they shared his view on the social role of documents and history: ‘When we write about a historical figure, we do not own any of the information about them. The documentation doesn’t belong to us’, he says, ‘only the way in which we narrate the story is ours.’

CAMeNA staff collected and catalogued boxes and boxes of material from his research on Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara. ‘One day I dropped in, just to see what it was like’, says Taibo, ’and I found 11 people from all over Latin America working with the documents I had donated on El Che. I was very happy to see that.’ Making history available to the people at large is one of Taibo’s life projects. He writes for a general audience, from the perspective of someone involved in social and civic movements from the age of 19, when he was part of the 1968 Mexican student movement. If people want to shape their present and their future in a critical spirit, and ethically, they have to know the past, that is, their own and other people’s history. Narrative has to give people a way into history, it must invite them, take them on the journey, not put them off.

Taibo sees his job as finding that narrative, with rigour, humour and passion. He likes to write about those who stand out for their irreverence, their heretical mindset, their non-dogmatic mentality, their non-sectarian involvement in struggles. The narrative emerges from what Taibo finds in the documents; he gives what he finds a shape and a voice, to reach people: ‘What are the drivers of narrative history? Curiosity, a critical vision of history, and a sense that ‘the story of this person has been told badly – if it is the story of a person. But sometimes it isn’t so much the story of a person, but the story of an epoch, or a movement, or the story of a long-term resistance.’ Once people read, they can take their own decisions; it’s up to them whether they put Dora the Explorer or el Che into their backpack, as Taibo puts it, tongue-in-cheek.

The collections he assembles when he researches contain different types of materials depending on the topic including interviews, newspaper clippings, photographs, the works of the people themselves, letters, and academic and historical publications. Each source has to be read and evaluated for its value, in its context, for its purpose. Out of this emerges a fabric, a panorama: ‘That is narrative history’, Taibo says, ‘In all this material you will suddenly come across a hidden phrase, maybe in an interview if you are writing about a person. This phrase will give you a clue about the person. Once the phrase shines and sparkles, you incorporate it into the text. And there you go.’

For almost six years now, Taibo has been director of the Fondo de Cultura Económica, a cultural institution run and funded by the Mexican State. Its remit is to make culture accessible to everyone, by publishing and selling books and promoting reading and debates emerging around cultural topics. To create a pathway into reading, Taibo and his team have launched a series of short, classical, easily portable illustrated texts, available in print or electronically, for 20 Mexican Pesos (£1) which are affordable to everyone, visually appealing, and which one can read almost anywhere.

Taibo and CAMeNA share a commitment and dedication to building and creating pathways for people who want to intervene in their historical moment based on ethical critical consciousness, whether that is by building an archive, creating an appealing and inviting narrative, or publishing books.