Slowly, the multitude advances one step forward, then another, only to remain immobile, rotating counter-clockwise little by little, with the Pyramid of Mayo to its left, and the Casa Rosada opposite, as the Madres have done, rain or shine, practically every Thursday afternoon for the past four decades. Some weeks only a dozen or so people accompanied them, but today, with several Madres assisted in wheelchairs, so many have come to the Plaza de Mayo for ‘round’ (as the weekly demonstrations by the Madres are known) number 2380 that they are unable to complete the circle.

It’s 23 November, and the Madres convened the protest for the first Thursday following the sweeping electoral triumph of the self-described ultraliberal, ‘anarcho-capitalist’ Javier Milei, as president of the Argentine Republic.

In middle of the crowd are 28-year-old Mariano and Ernesto who is 70. ‘We didn’t know each other before and yet we now know everything about the other,’ says Mariano. ‘I am neither with the peronistas or the far left. I can’t absolutely define myself because I am critical of both. But this social cause has no political party.’

49 years ago, on 1 May 1974, Ernesto was in this same place, and heard president Juan Domingo Perón insult the thousands of Montoneros present who had previously supported him, calling them ‘young imbeciles’ (‘imberbes’) and prompting them to leave the square. The empty space left in their wake became a chilling forecast of the thousands who would become missing.

Ernesto’s girlfriend ended up abducted by agents of the state and to this day is a victim of forced disappearance. Ernesto survived political imprisonment and today strung over his chest is a sign written in black marker reading: ‘There were 30,000.’

Mariano, who was born in the period of democracy, and Ernesto, who bears the dictatorship engraved in his being, share perplexity and indignation that fellow citizens have elected a president who places in doubt the severity of the human rights violations committed by the last civil-military dictatorship. They also share the tremendous resilience characteristic of many Argentines that has enabled them to lift themselves up to demand justice and memory.

Now both turn their attention to union leader Daniel ‘Tano’ Catalano. With so many people in front they can barely see him but they plainly hear him say, ‘This is a time of much uncertainly and it’s hard to think clearly about how to proceed. But we will lift ourselves up once more and soon see how to construct. We are here to launch our bodies into action and continue forward.’

We will not shut up; nor will we in our bitterness sit down and cry

When it is her turn to speak, Carmen Arias, a well-known figure of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo organisation, quotes the words of historic leader Hebe de Bonafini, deceased a year ago. The government of Javier Milei ‘…must be resisted. We will not shut up; nor will we in our bitterness sit down and cry.’

During the first televised debate on 1 October between the five presidential candidates, Milei, who launched his political career just two years ago when he was elected to the national Congress, stated ‘There was a war and the State forces committed excesses.’ Later in the campaign, the Human Rights Secretariat was just one of the ministerial entities that he promised to close.

A few days before the election the future vice president Victoria Villarruel affirmed that the premises of the former Navy Mechanical School (Escuela Mecánica de la Armada, ESMA), which since 2015 houses the Museum of Memory and where human rights organisations have their offices, should be converted into ‘a school, which all Argentines need.’ 1)This is not the first proposal to destroy the ESMA space of memory. In 1998, president Carlos Menem sought to demolish it but survivors filed an injunction that was accepted by the court, thus protecting elements of proof related to crimes committed there, which is named in 300 court cases. This past September, the place Villaruel would shut down was declared a World Heritage site by UNESCO. At the ESMA an estimated 5,000 people were tortured and murdered from 1976 to 1983. Only 500 survived.

The new president’s expressions cast doubt on the perception that a human rights culture has become firmly rooted in the 40 years since dictatorship came to a close in Argentina. Debate continues regarding how to interpret the fact that the youngest voters (in this recent election, 16-year-olds voted for the first time) gave Milei his decisive electoral push. Is it due to lack of conscience? Are they fed up with corruption? Felipe, an 80-year-old Argentine who now lives in a European country, is of the opinion that: ‘Generally the old guys are blamed for conservative trends but this time the youngest voters elected Milei. The memory of the 30,000 disappeared and human rights is not their problem. They are tired of having to leave the country to find work.’ 2)Conversation 22-11-2023

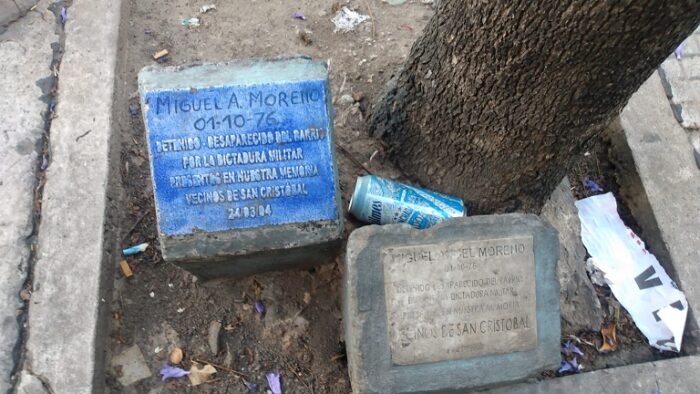

Walking along the streets of many Argentine neighbourhoods, one may stumble upon another indicator of the strength of historic memory. ‘Here lived…’, ‘Here worked…’, ‘Here was abducted by state terrorism…’ is the wording on colourful ceramic tiles installed in the sidewalks in more than 3,000 sites in the Argentine capital and in the provinces.

These are everyday memory markers of the artistic-political project known as Barrios por la Memoria y Justicia (Neighbourhoods for Memory and Justice), that was launched in Buenos Aires in late 2005.

In Chile, where expressions of memory are commonly vandalised – as happened with the mosaics installed in the sidewalk and repeatedly broken outside the Venda Sexy torture center where the notorious DINA agent Ingrid Olderock worked – Chilean human rights memory activists admire the apparent respect that Argentines exhibit. However, similar attacks have been noted with increasing frequency in Argentina as well since the government of Mauricio Macri and up to the present.

Strolling through the quiet Buenos Aires neighbourhood of San Cristóbal where he teaches in a secondary school, the social psychologist Enrique Ramírez Concha comes across several memory tiles that have been vandalised. The son of Chilean social activists, including his aunt Herminia Concha who was an emblematic figure of the resistance, Enrique came to Argentina as a child more than 45 years ago when his parents fled the Chilean military coup.

Since earning his degree in 2003 from the Universidad Popular Madres de Plaza de Mayo, Enrique teaches children’s rights, women’s rights, and human rights in general at several secondary schools. Every 24 March, on the anniversary of the last military coup that took place in 1976, schools hold special commemorative events, sometimes attended by a Madre or Abuela who tells their story. ‘Over quite some time, the Tiles of Memory were respected. But now you often see them hatefully broken with vengeance. They are repaired and then the vandals break them once again. You ask yourself what happened. Why don’t some people want to preserve this memory? Yet no matter how much the younger generation that voted for Milei prefers to forget, memory will endure.’ 3)Conversation 22-11-202

One of the memorial tiles that Enrique notices whenever he is in San Cristóbal bears the name of Miguel Ángel Moreno Malugani, whose life was marked by persecution in three countries. Moreno was an Uruguayan who arrived in Chile in 1972 to escape persecution in his native country. After the military coup upended Chile, he fled to Argentina, where, in October 1976, he was forcibly disappeared by repressive agents, at 28 years old.

Many of the tiles, fashioned collectively by relatives and the friends of the disappeared, have encrusted in the surface small squares or rectangles of coloured glass, like pieces of hard candy. These are created by the visual artist Marisa Munczek, an active participant since the group’s inception.

The project, explains Marisa, ‘addresses people who are well aware of that history as well as others who know nothing about what happened. They mark the footsteps among us of those who died because they dreamed of a better world. The tiles are colourful because they celebrate life; these are not tombstones.’

She affirms that ‘Negationism is not new. It always has existed in Argentina. We have seen it in the attempts to protect the military from prosecution. This violence against the tiles – and the Nazi symbols painted on the walls of schools and hospitals – has been unleashed now because the negationist discourse of the new president and especially the vice president authorises it.’ 4)Conversation 5-12-2023 A tile that was attacked right after the election was restored this past Saturday.

In 2008, neighbors of the Almagro district of Buenos Aires placed a tile in front of the building at 2583 Corrientes Street, where the physicist Gerardo Strejilevich lived at the time he was abducted by repressive agents on 15 June 1977. His sister Nora, also abducted that day, is a witness-survivor and writer known on both sides of the Andes for her reflections about the persistence of memory. She and Marisa were at the Plaza de Mayo for the demonstration (round number 2380).

She recalls what Argentine cultural critic Alejandro Kaufman had to say about denial of a massacre or genocide: ‘…it does not intervene the past, rather it speaks to the future, and its objective is to tear down the barriers that have been lifted to prevent repetition [of human rights violations]. Therefore, in both Argentina and Chile, the fight for Never Again has become a fight against the discursive erasure to eliminate what exists, existed and will always exist: the resistance of memory’. 5)Electronic mail correspondence 8-12-2023. Books published by Nora Strejilevich include Una sola muerte numerosa (1997), El lugar del testigo (2019), and Un día, allá por el fin del mundo (2019).

In the 21 days that transpired between the election day of 19 November and the presidential inauguration of 10 December, Milei appears to have quietly dropped some of his most extreme proposals. He is no longer openly calling for the dollarisation of the economy, closure of the Central Bank, or ending diplomatic relations with China and Brazil.

The opposition hopes that his threats to close many cabinet ministries and to privatise state-owned firms such as the successful YPF energy company and Aerolíneas Argentinas were simply campaign bravados. If Milei attempts to implement some of his harshest measures, he will have to surmount an opposition majority in Congress and likely the ire of Argentines who are known for massive street mobilisations in response to injustice.

Argentine lawyer Pablo Llonto, who represents Chileans in the Operation Colombo case, describes the road he recommends human rights advocates follow. ‘We have to multiply efforts to disseminate the dictatorship’s horrors and those responsable for those human rights violations. We must tell people about how factories were destroyed, jobs were lost and the country was sunk. That’s why historic memory work is so important. But we must be good teachers too: point out examples, show hard data, and talk about the crimes. Court cases will continue and we will not cease to bring claims to the judiciary, despite all the current difficulties and those to come.’[i] That spirit of resilience is reflected in Marisa’s words: ‘Every time a tile is vandalised, we will restore it. Memory cannot be erased, and it will never be destroyed.’ 6)Electronic mail correspondence, 30-11-2023

Maxine Lowy is author of Latent Memory: Human Rights and Jewish Identity in Pinochet’s Chile (2022).

References

| ↑1 | This is not the first proposal to destroy the ESMA space of memory. In 1998, president Carlos Menem sought to demolish it but survivors filed an injunction that was accepted by the court, thus protecting elements of proof related to crimes committed there, which is named in 300 court cases. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Conversation 22-11-2023 |

| ↑3 | Conversation 22-11-202 |

| ↑4 | Conversation 5-12-2023 |

| ↑5 | Electronic mail correspondence 8-12-2023. Books published by Nora Strejilevich include Una sola muerte numerosa (1997), El lugar del testigo (2019), and Un día, allá por el fin del mundo (2019). |

| ↑6 | Electronic mail correspondence, 30-11-2023 |