In August last year, with the 50th anniversary of the coup d’état in Chile fast approaching, the editorial group at LAB decided that to mark the occasion, someone should interview Mike Gatehouse about his experiences, given he was one of the handful of British people living in Chile at the time to have been arrested by the military. That someone turned out to be me, Tom, a longtime LAB editor and Mike’s son.

I had heard Mike talk of his experience of the coup in the past, but never at such length or in such detail. And yet, I still feel there are certain aspects of this story –perhaps some of the more painful or personal ones– which remain elusive, unknowable.

Nevertheless, this very personal interview serves as a valuable piece of historical testimony. Beyond that, and more importantly, it is a reminder of the energy and optimism that fuelled Popular Unity – a movement which remains a symbol of a democratic path to socialism and of hope for a more egalitarian future, not just in Chile, but worldwide.

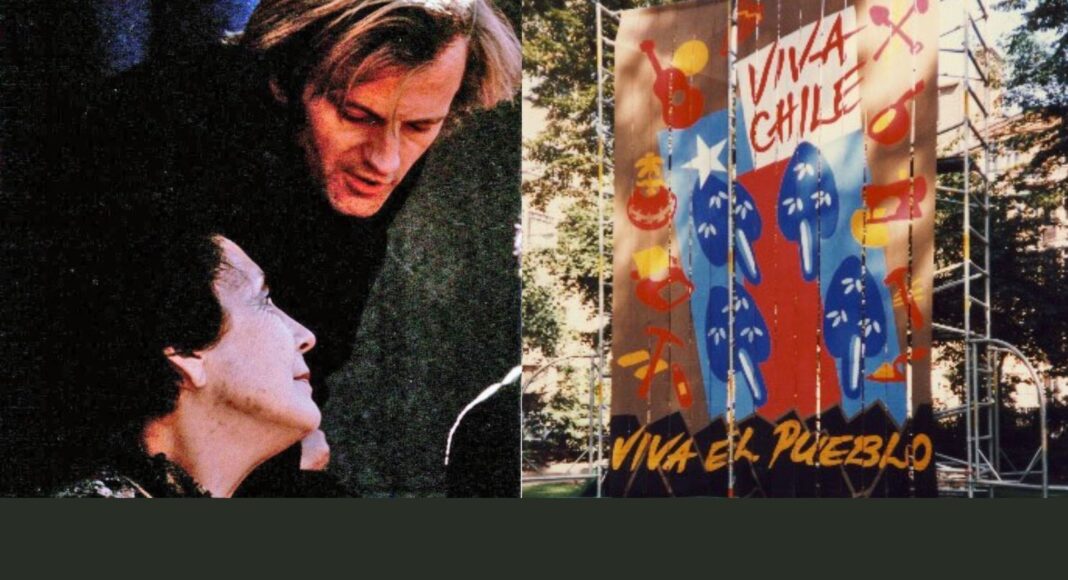

Main image: Mike Gatehouse with Hortensia Bussi (de Allende)

Tom Gatehouse: Today is 11 September 2023, which means it’s exactly 50 years since the military coup in Chile. Tell me your memories of that day. Where were you? What did you do? What exactly happened?

Mike Gatehouse: Well, it’s 9:40am now, so at this time in Chile on 11 September 1973, I was trying to reach my workplace, which was the Instituto Forestal [the Forestry Institute], located in a relatively wealthy suburb up towards the Cordillera on the eastern side of Santiago. By then it was already apparent that a military coup of some kind was underway. There had been firing in the centre of town. Cars and buses were fleeing the centre in panic. I saw four cars full of what seemed to be the staff of the Chinese embassy going at high speed along one of the avenues out of Santiago.

On my way on foot I passed the offices and printing works of El Siglo, the Chilean Communist Party’s daily newspaper – which was quite a big circulation paper then – and saw the print workers calmly unloading big rolls of newsprint from a lorry. So I thought, ‘Well, things can’t be so bad.’

But by the time I reached the Instituto it was apparent that things were really bad. There was an assembly under way in the canteen. The headquarters of the Instituto was quite a big place. There were offices, laboratories, vehicle parks, etc. Some people were departing to collect their kids from school; others who presumably had tasks assigned to them by their political party or trade union were heading off in different directions.

Most of us stayed in the canteen debating what to do and listening to the by now military broadcasts – because the military had taken over the remaining radio stations and bombed the transmitters of those which supported Popular Unity.

A number of us decided to stay at the Institute to guard the premises because there had been repeated acts of sabotage against government offices of all kinds in the preceding weeks and months. So we stayed on and wandered around, in a state of shock really. I suppose most of us believed that – although undoubtedly there was military activity – that there would not be a united military uprising against the government. And we expected to hear news that one regiment or another or some loyal general would be gathering forces somewhere or other, not necessarily in Santiago, perhaps in some other part of the country. But the news didn’t come, and it became coldly apparent by about three in the afternoon that this was for real and potentially long lasting and catastrophic in its effect.

TG: So even on the day of the coup itself, there was still hope amongst you and your colleagues that the worst hadn’t happened?

MG: Yes. I think on two grounds: one, a belief that there were still loyal sectors of the army, or at least ones that wouldn’t join in the coup. That was quite a strong belief, however misguided, but nevertheless strong. And secondly, a disbelief in the effectiveness of the armed forces to manage a total takeover of the entire country and its government and institutions in such a short space of time – and to this day I don’t know how that happened. I strongly believe that it was with substantial communications, tactical and organisational support from outside Chile, primarily from the United States.

TG: So what was the atmosphere like at your workplace?

MG: Intense sadness. I remember meeting a colleague in the corridor and just hugging them and saying goodbye with a sense that perhaps this would be goodbye forever. There was a real sense not of doom, but of sadness. I suppose we were already, to some degree, accepting the catastrophe. We knew somehow that this would change everything.

And indeed, all of us foreigners at the Institute were later automatically suspended from our jobs, sacked in effect with no nothing: just don’t come back. The Institute itself was subsequently privatised and ceased to exist.

The military had a fanatical, borderline irrational hatred, not just of Popular Unity and its supporters, but of all government institutions that had been carrying out its policies or initiatives.

Some of us were arrested. The director and a number of the more senior people at the Institute were arrested that night, the night of the 11th, and taken to the local police station and quite badly roughed up. Some of them became prisoners in the National Stadium, as I did later.

I think it’s hard to imagine how totally a world can be turned upside down, so that everything that had been normal, legal, part of your work, part of your life, in the space of 24 hours became deviant, illegal, insidious, seditious, dangerous and a matter of life and death, where your life was imperilled.

TG: What did you do after work that day?

MG: By mid-afternoon, numbers had thinned out. People had gone home or gone elsewhere. And I suppose about maybe 20 or 30 were left, including about 8 or 10 of us who were foreign nationals. The Institute had been quite an international place. For instance, there were a couple of people from Finland who were forestry specialists, Venezuelans, people from all over. By early evening, we were hearing among the military broadcasts denunciations of ‘foreign terrorists who had come to Chile to murder our families’. We decided maybe it wasn’t such a good idea for us to stay there.

So we went to the house of one of our Chilean colleagues who lived nearby and spent the night in an outhouse at the back of his house. The following morning we went back to the Institute to find that during the night the police or military had raided. There were bullet marks on some of the doors where they presumably shot out the locks, and nobody was there. The Chilean staff who had stayed had been arrested, including the director. So this group of us who’d slept elsewhere wandered a bit aimlessly around the institute and spent some of the time going through people’s offices, destroying things like lists of trade union membership, party membership, posters, leaflets, anything that could be incriminating.

And this was one of the many extraordinary acts of self-censorship that occurred all over Chile that day. People buried their own books and posters and anything political that could identify them. Subsequently, of course, the military went house to house doing the same thing with great brutality and much more thoroughness. I don’t know what time it was, maybe about 10:00 in the morning or perhaps earlier on the morning of the 12th. By this time, the military were in total control. They proclaimed a permanent curfew. Not a night-time curfew. A permanent curfew. Indefinite.

But some people came across the fields from one of the nearby shantytowns. They were the cleaners at the Institute. And they found us and said, ‘Compañeros, you must get out. It’s been raided once. If you’re detected here, it’ll be raided again. Come with us’. And so we went with them across the fields and they hid us in the shantytown, at manifest risk to themselves and their families. And I spent the next two nights in hiding in the house of this man – I don’t even know his name. He fed me and was tremendously supportive. When the curfew ended, I left, because I sensed that I was a danger to him, and made my way to the houses of other colleagues and stayed with them off and on for the next ten days or so.

The man whose house I stayed in was trying to manufacture bombs. Obviously, he was part of whatever resistance existed in the shantytown, and he was literally stuffing some kind of gunpowder – not dynamite, but some explosive powder – into the base of hollowed out candles. Lord knows what effect these would have had, if any. But I slept on a bed with explosive-filled candles underneath me.

TG: What were your thoughts when you were there? What were you planning to do?

MG: Well, in the instant before we left the Institute with one of the other colleagues, I think from Venezuela, we discussed, absurdly, trying to escape over the Andes to Argentina, because we were very close to the Andes foothills. But also at that point, the cordillera is extremely high – 18,000 feet plus. And although there are passes, it’s vanishingly improbable that we could ever have made it, simply in terms of physical feat, let alone if there were any army patrols to stop us.

There was a great sense of not knowing and also being cut off from anyone who could tell you what to do. We expected that maybe there would be radio. I suppose more generally, though, what we hoped and expected was that there would be some nucleus of resistance, whether armed or not, but somewhere we could go to and collect together with others who were supporters of Popular Unity.

That was not just a hope. It was an expectation that there would be such centres that one could try to reach. It might not be easy, but we would go there and then join in whatever form of defence of the democratic government or rebellion against an imposed military regime, whatever that would amount to. But nothing emerged. There were no calls, no credible voices elsewhere in Chile. There were isolated pockets of resistance in some of the shantytowns in Santiago; in one or two of the factories, especially in the Cordón Cerrillos, which was one of the industrial areas of Santiago with very strong trade union organisation and presence; and in one of the nationalised forests in the south of Chile where the Instituto Forestal worked, at Panguipulli. But those were very rapidly, brutally exterminated, those groups that were resisting. People were simply killed by the military.

TG: How did you come to be in Chile? First of all, what was it that had attracted you?

MG: I did Voluntary Service overseas (VSO) in Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia). Later, I got a scholarship to study Development Sociology at Cornell University in the US. I went there expecting then to orient my studies towards Africa and go back to Africa, perhaps to Tanzania, which offered a kind of African socialism at that time. But when I got to Cornell, the African Studies Department was very depleted, very poor. There was not much going on.

But on my course I rapidly met a number of Latin Americans and got interested in them and their countries. And they said to me, ‘If you want to see a really vital and interesting and promising experiment, you must go to Chile. That’s where it’s all happening.’

And indeed, not just people like myself, but people from all over Latin America with a progressive outlook, those who could, converged on Chile, including many political exiles from countries like Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay, and later on, Argentina.

TG: How long had you been in Chile prior to the coup?

MG: I arrived in March 1972, almost exactly halfway through the Popular Unity government, and the coup took place in September of ‘73. So I had 18 months of living in Chile under Popular Unity. It was an extraordinary experience. I mean very, very intense, enormously optimistic. Lots of good, wonderful, unprecedented things happening.

But it was also a time of mounting difficulty as the right-wing opposition got its act together after being initially divided and demoralised following Allende’s election in 1970. In March 1973 – so six months before the coup – there were congressional elections. And contrary to the expectation of the right, which through the very influential wide circulation newspapers it controlled had counted on the population of Chile reacting against the economic difficulties, the shortages of some common products and food, rising inflation, a certain degree of chaos, and certain divisions within Popular Unity about the best way forward… all of that led the opposition to expect that they would do better at those congressional elections. And they didn’t. They did marginally worse.

So Popular Unity emerged, if anything, with a slightly better democratic mandate than it had had at the presidential elections in 1970. And there were still at least two and a half years to go before the next presidential election.

It was crystal clear at the time, but more so now in retrospect, that the decision of the powerful economic sectors behind the main opposition parties – which increasingly included sectors of the Christian Democrat Party which was regarded at the time as centrist – within the military and most importantly and most powerfully in the US government: the Nixon government and the US intelligence community, that their conclusion was: A) that they were not going to win by democratic means; and B) that they couldn’t afford to wait another three years for Popular Unity to consolidate. Therefore they decided to move from economic boycott and economic sabotage to direct violence and physical sabotage of the government and its institutions. And ultimately, if that were insufficient, then to a military coup. So they hatched that and pursued that strategy relentlessly from March 1973 until the time of the coup in September.

There was an abortive coup in June, on the 29th of June, widely referred to as the Tancazo. One regiment of the army, a tank regiment, mutinied and drove their tanks towards the centre of Santiago and surrounded the presidential palace. It was in some senses a ludicrous operation and was very rapidly quelled and suppressed by the main army, and the conspirators surrendered and were imprisoned. I don’t know for how long, but anyway, they were imprisoned and some of the civilian co-conspirators fled the country.

Whether that was a dress rehearsal or whether it was a hothead military commander jumping the gun, nobody knows. To us at the time, it felt like a dress rehearsal because although it was crushed, we had the sense very rapidly that this was by no means the end of the story and that more serious attempts would be made. And that turned out to be so.

By the end of August, beginning of September, the right was sponsoring major strikes or lockouts, paralysing road transport, sabotaging vehicles; for instance, the vehicles of the Forestry Institute could no longer safely travel to the south of Chile where the forests were because they would be ambushed on the road and the vehicles destroyed and the drivers and staff roughed up or injured. So by the beginning of September, it was clear – and the Communist Party of Chile told us more or less officially – that Chile was in a de facto state of civil war. So there was a heightened expectation of military movements.

And if there were any doubt about that, there were already manoeuvres against generals who were loyal to Allende. For instance, Carlos Prats, who was the commander in chief of the armed forces until sometime, I think in July, was forced to resign when the wives of his fellow generals demonstrated outside his house and strewed grains of maize corn on the steps of his house implying, ‘You’re chicken, you’re a coward. You’re not going to rise up against this tyrannical left-wing Marxist conspiracy of a presidency.’

And General Prats resigned because he either had to resign or attempt to purge the leadership of the armed forces. He didn’t have the political strength to do that, and perhaps not the political will. Bear in mind that he was subsequently assassinated in Buenos Aires by a commando of Pinochet’s intelligence organisation, the DINA. Later, several other prominent ‘constitutionalist’ military officers were imprisoned. General Bachelet, a senior aircraft Air Force officer who’d been in Allende’s cabinet, responsible for food distribution, was imprisoned and died there, effectively killed by a savage prison regime.

So the chips were down. By the 4th of September it was clear that something was going to happen. There was a huge demonstration in support of Popular Unity and Allende, and I can remember marching with others down the avenue in front of the Moneda Palace, and Allende was on a temporary platform erected outside the palace waving to the crowd. I suppose I must have passed quite close, perhaps within 50 yards or so. And you could see his face deeply furrowed by tiredness. He looked exhausted, and I think by then he was.

TG: In the article that you published on the BBC after Pinochet was arrested in ‘98, the tone quite heavily seems to imply that you knew what was coming – and yet you stayed. I’ve wondered about that decision. Were you not tempted to leave? Did you not think ‘this is going to turn really ugly’?

MG: On a personal level, I felt completely, perhaps romantically or unrealistically, but completely committed to the Popular Unity project. Not necessarily in a political membership sense, but I was utterly committed to what Popular Unity was trying to do in Chile. I’d decided already before then that I wanted to stay in Chile for a long time, probably indefinitely, make my life there and do whatever I could to contribute to that process. And so for me, leaving at that stage was not an option. I don’t think it occurred to me.

TG: How had you been contributing to the Popular Unity period? You talked a bit about the job at the Forestry Institute. Can you talk a bit more about that and also any other activities that you were involved in?

MG: I knew nothing about forestry beforehand and I was working in a technical capacity as a computer programmer and statistician, but it was clear that forestry was one of the major potential growth areas for Chile. In the south of the country, pine forests in particular grow very quickly because there’s very high rainfall and a comparatively temperate climate. Popular Unity had highlighted it as one of the industries it wanted to encourage and promote and grow. If I could contribute to that, I felt that already I was doing something valuable and worthwhile.

Outside of work at the Forestry Institute, I’d gradually drawn closer to members of the Chilean Communist Party and I’d applied to join the Party at my place of work before the coup, probably in about July ‘73. They were understandably wary of admitting foreigners and I hadn’t had a reply as to whether I could join. But I did attend some branch meetings.

I also had Communist friends in the neighbourhood where I lived, quite a poor neighbourhood close to the centre of Santiago, only about five blocks from the Moneda Palace. It was an area around the bus station where all the buses left to go to the south of Chile, an area of small bars and brothels and where a lot of people lived, who worked in shops, car repair places, sewing workshops and so on. Quite an interesting area, not much organised either by left or right and where people were quite volatile in their affiliations. Some were very clearly pro Popular Unity, others ambivalent, others against or even quite right wing.

Part of the difficulties Popular Unity faced in 1973 were food shortages, greatly exacerbated by deliberately organised shortages and black marketeering sponsored by the right-wing political parties. I strongly suspect that on CIA advice they would do things like publish a headline in one of the newspapers that they controlled, saying ‘toothpaste will run out tomorrow.’ So of course everyone goes out and buys toothpaste and duly toothpaste does run out tomorrow – it’s self-fulfilling. Once toothpaste does run out, people want toothpaste. So they’ll go to the shop and offer to pay over the odds for a tube of toothpaste from behind the counter. Shopkeepers – not necessarily evil people, but not stupid – can see the gain in doing this. So shopkeepers on a mass scale from big stores right down to tiny corner shops were black marketeering. They wouldn’t have described it as such themselves, but that’s what it was. And they were making profit by doing so.

So Popular Unity set up an organisation to distribute to community organisations, local community organisations, key products such as cooking oil, flour, I think some kinds of meat, sugar, soap, etcetera, at official market prices. People in communities were encouraged to form organisations which were called juntas de abastecimiento y precios – supply and price organisations – and we set one up in our barrio.

This was an eight- block city neighbourhood with a mixture of flats, tenement buildings and conventillos, one room tenements along a passageway that were common in older parts of Santiago. We had 1,200 families enrolled in our organisation in that tiny city area and every week we had a system of distributing coupons to them depending on the number of people in their family.

And they could then go to the little corner stores that they normally used and obtain essential goods at official prices. And we, the organisers of the committee, had to make sure that we distributed the officially sourced, officially priced products to these little shops. I used to cycle around my neighbourhood with one of those delivery tricycles taking boxes of soap or flour or cooking oil or whatever from one shop to another to make sure there was enough to cover the coupons that would be surrendered at that shop.

It was kind of insane, but at the same time, it was moving and it had a sense and it did have a significant impact on the black market. It didn’t eliminate it, but it helped to reduce it. And you could almost see a sort of battle going on day by day between official prices and black market prices.

We had weekly meetings in a big church hall with up to a couple of hundred people who would turn up and often shout at us because they hadn’t had their quota of whatever. And we tried to respond to their requests and demands and meet them. It was a very hands on, live, grassroots experience of community organising, albeit in a way and for a purpose that wasn’t entirely rational.

TG: I’ve heard you talk a lot about your arrest. You talk about coming back to your flat, though you had been advised against it. Why was that? Did you not think you were in danger? How conscious of the danger were you at that point?

MG: Well, I supposed that things had calmed down a bit. I had no particular reason to think anyone was looking for me. Perhaps what I was not sufficiently aware of was that some of our right-wing neighbours had it in for me or us – myself, and the two Chileans I was living with there at the time. One of them, Wolfgang, worked at the State Technical University, the UTE, and he was a member of the Communist Party. We had both been involved with the Junta de Abastecimiento y Precios in our barrio, so we were fairly well known. I’d spoken on, as it were, public platforms.

In our street, the flats were maisonettes above a row of shops. And one of these little corner shops was owned by a woman who was broadly sympathetic to Popular Unity. The other was owned by the wife or widow of a police detective who was pretty hostile to Popular Unity and towards us. And those two women were at daggers drawn with one another. Subsequently, I learned that somebody, possibly the right-wing shopkeeper or possibly another neighbour, had claimed that we – myself and my flatmates – had stored a cache of arms in the patio behind the flats, which was absurd, to put it mildly, since the patio was visible clearly to all the other flats and it would be the last place anyone would choose to hide anything.

The police had raided our flat twice already before I got back there, and it was in a fair state of disarray. Also, my flatmate had been trying to purge it of left-wing literature and books and stuff like that. I went back there to collect clothes. This was nearly ten days after the coup and I hadn’t had any change of clothes. I was desperate to get the basic things.

I was only there for about an hour or so. I was just packing up to leave. As I opened the door, the police were coming up the stairs and along the passageway to arrest me. There were 8 or 10 police, guns in hand. And it was pretty clear that that was it. I tried to walk past them, pretending ignorance, but they grabbed me and took me off in a police bus to the nearest police station, the Comisaría de la Octava Comuna, which was in Calle San Francisco. There they stood me up against a wall. One of the officers said to the others, ‘This one’s dangerous. If he moves, shoot him.’ They said that I was a Cuban terrorist, which seemed mildly improbable given my blonde colouring and English accent. However, later in the afternoon, they put me in a cell, facing onto the police courtyard with a grille in the door, and I watched as bonfires of books and papers were burned in the courtyard of the police station, presumably stuff they’d seized from mine and other flats.

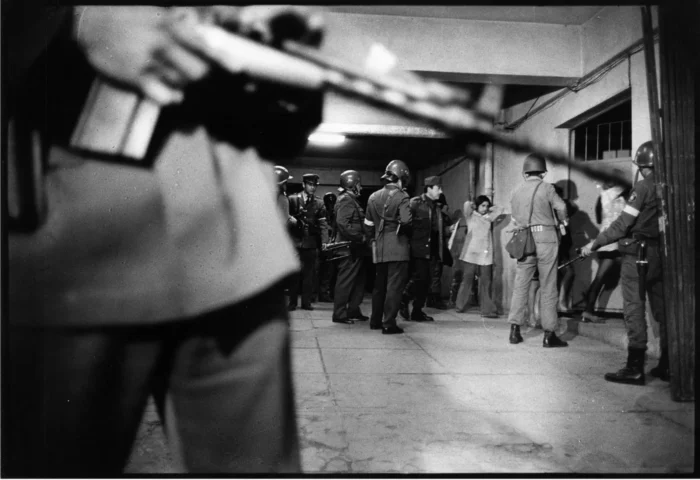

Some time later on, we were taken out, myself and one or two other prisoners from that police station. We were made to lie flat on the floor in the aisle in the centre of a police bus, while armed police stood over us with submachine guns pointing at us. And we were driven to the Estadio Nacional, which was about a mile, mile and a half away in the barrio of Ñuñoa.

When I got to the Stadium, we were taken out at gunpoint into a wide assembly area in the entranceway where lorries and buses bringing in prisoners were disgorging groups of prisoners singly or in groups. We were marshalled by armed soldiers into wherever we were going to be processed. It rapidly became clear that they had very little idea of who was who – there was no paperwork that I was aware of. You were simply handed over to be taken prisoner in the Stadium. I was taken and put into a cell, which was one of the changing rooms under the stand in the stadium.

This was Chile’s equivalent of Wembley Stadium, where all the national matches were played. It’s a big oval shape with the seats in banks upwards from the pitch and underneath the angle of the stands there are administrative offices, team changing rooms and so on.

We were put into a team changing room. There were about 130 prisoners there with me. We were so tightly packed that at night the only way we could lie down to sleep was by lining up in rows and dovetailing heads and feet to lie down. There was a complete mixture of prisoners, the majority Chilean, some from government offices, some from factories or working-class areas. Some who had just been picked up off the street at random. And some foreigners.

In the changing room next to us were women prisoners, and they were an extraordinary group. They had seemingly much higher morale, or courage, than we did. They sang songs to keep their spirits up, and they sang songs to us to keep our spirits up. And as the days passed, they got to know the soldiers who were guarding the cells. And the soldiers were mostly raw recruits who probably had very little idea of what was going on. They were just acting under orders. And the women sort of teased them and not exactly made friends, but established a relationship with them, got them to give them cigarettes. And then the women would pass the cigarettes through a grill to us in the next-door cell. It was an astonishingly heart-warming experience.

There was a woman called Marta Cabrera, a Yugoslav national who’d been married to the treasurer of one of the main copper mines, I think Chuquicamata, in the north of Chile. Her husband, herself and their children had been seized by the military on the day of the coup. They’d been separated, but she learned later that he’d been shot. She was taken by plane to Santiago and then to the Ministry of Defence, separated from her children. She was pregnant at the time and they beat her in the stomach until she had a miscarriage and then brought her to the stadium. I saw her months later in Helsinki at a meeting held for victims of the coup to give testimony before an international audience – an extraordinarily brave and impressive woman. And she had been in the women’s cell at the same time I was next door in the men’s cell.

The stadium was divided into segments by the passageways that led through and by the stairways up to the stands. Each segment was divided from the others by barriers, barbed wire and machine guns mounted in a sandbagged embrasure. There was an atmosphere of being in a concentration camp under military guard and constantly intimidated.

I didn’t myself witness torture, but a prisoner in my cell who was at times sitting next to me, a Brazilian engineer, was tortured. He was taken out while we were there, taken off for interrogation. He said that he was hooded, beaten around the head with a wooden bat until he was almost deaf, and that he detected that some of those interrogating him were Brazilian intelligence officers.

Chile, before the coup, had been a point for people from all over Latin America to come, many of them left wing or of left-wing sympathies, and some who were de facto refugees from other countries, notably Brazil and Uruguay. Immediately after the coup, probably by previous agreement or plan, intelligence officers from the military in those other countries started to arrive in order to find, identify and interrogate and possibly take back or kill those who they were seeking.

TG: Did you get the feeling that the police actually knew who you were and what you did, or simply that they’d acted on this tip and that was good enough?

MG: I think primarily the cause was the tip. Secondly, it was the denunciation – if it’s true that that was made – that we were hiding arms. Bear in mind that that was the sort of constant propaganda of the right wing and of the military both before and after the coup, that ‘these left wingers are hiding arms in order to attack us and our families.’ I don’t know whether individual police recognised me. It’s possible because the police sometimes controlled the queues at the shops which we from the Junta de Abastecimiento y Precios were also involved with. They might well have seen me and I stuck out because I was a gringo, a rubio and a stranger, evidently not a local person.

I was extremely frightened while I was in the police station. The police were, in a sense, in a state of hysteria. I believed that they probably had not been home since the coup. They’d been on permanent duty, probably sleeping in the police station. They had been told that they and their families were under risk of attack. There were some stories at the time that both police and soldiers were given drugs to increase their state of alertness and aggression.

I don’t know if that’s true or not, but I also heard that specifically the police station in my community had divided on the day of the coup, and police loyal to Popular Unity had had a shootout with the police who had joined the coup. If that’s true, it would certainly explain the heightened sense of hysteria, aggression. I was myself profoundly relieved when they took me to the stadium because it soon became apparent that nobody there knew who I was.

TG: I’ve heard you on several occasions relate the story of your arrest and your detention, often in great detail, but you’ve never really talked very much about how you felt during this experience. Can you talk a bit about that? What was going through your mind? Did you think that there was a way out of this? Or were you trying not to think too far into the future?

MG: I think you need to have a sense not just of my own feelings, but those of pretty much everyone who supported Popular Unity in Chile at the time. No matter what had gone on before the coup, the coup itself was a shock of the most extraordinary and profound nature. It wasn’t just a few shots fired around the presidential palace, change of the guard type of thing. It was the most thorough, total and devastating destruction, not just of a government, but of the whole legal framework of democracy. The electoral registers were burned. Congress was padlocked. It was utterly complete, much different from coups elsewhere in Latin America, both at the time and previously. This was not at the end of a war where the country was in ruins, like Germany in 1945. This was a country fully functioning with all its normal institutions, apparatus, state courts, judiciary, all the rest of it functioning.

And then from one day to the next, the whole of that apparatus is paralysed, parts of it are destroyed, and most of it is substituted by an entirely new regime under direct military control. Not only did the military order the electoral registers to be burned, but they replaced the rectors of every university in the country with military nominees, some of them serving or retired military officers, some of them just people of their confianza, their confidence. The directors of many, if not most, secondary schools, the mayors of virtually all towns. It was an astonishingly complete coup. And the effect on all of us was one of, you know, complete shock.

People really didn’t know how to feel, how to address this. There was a deep sense of grief. There was a sense of disbelief that it could be so complete. There was a sort of vague, gradually diminishing, hope that there would be a focus of resistance to which we could in some way join. There was a determination on my part and everyone else’s part that I knew to resist, to fight this if we could. But there was no means. You couldn’t pick up a gun and go out in the street and shoot a soldier. Even if you’d had a gun, that was completely unrealistic. There were heroic acts of resistance, but workers trying to resist were exterminated. There was a nightly curfew, I think from quite early, something like five or six p.m. through till dawn. And if you were caught on the streets, you were shot. There was no argument.

By this time the newspapers had resumed publication, albeit right-wing newspapers. The radios under military control were transmitting military communiques, but then subsequently beginning to transmit news of a sort under heavy censorship.

There were photographs, television images of bodies found in the Rio Mapocho, the river that flows through the centre of Santiago. Bodies were found in the street. Well-known people had been murdered. Allende had been killed. Whether he committed suicide or was shot is not clear. Victor Jara had been murdered. There was a murderous atmosphere. And so all of this filled people with grief, but I didn’t want to leave. Even after my arrest and after my release, I didn’t want to leave Chile. I wanted to stay if I possibly could. But it became apparent once I was released that I couldn’t realistically stay. My job had been abolished, suspended. I couldn’t go back to work. I’d talked to colleagues at the Institute and they said ‘No, all the foreign employees have been sacked.’ I didn’t even have a passport because my British passport was at the time of the coup with the Ministry of the Interior for my visa to be renewed. Without a job, with no income, I had no means of survival. I realised that I had to leave. Perhaps if I’d had more imagination or courage, I might have stayed. But then I didn’t have anyone to associate with, to group with, to join with, and certainly nobody who I felt would not be more endangered by associating with me than they would be helped. So it made sense to go.

I was rescued from the Stadium by the British consul. He took me out and drove me directly to a diplomatic residence, the residence of the first secretary of the British Embassy, a man called Peter Summerscale. And I stayed there in his house until they took me directly to the plane and drove me in a diplomatic car to the steps of the plane that would fly me to Argentina and thence back to Britain.

TG: How did the British consul discover your whereabouts? And what do you know of any attempts that were made back home to secure your release?

MG: I know that my parents were very worried because I hadn’t been in touch with them since the day of the coup. I’d been frightened to phone internationally or do anything because I assumed that all phone calls would be monitored. I’m sure they were.

They were worried. They’d contacted people they knew. My former student colleagues in the US at Cornell University had started some sort of campaign for my release. So the fact that I was missing was known, and presumably the British Embassy found out; whether they were notified by the military or they themselves went to the stadium, I don’t know. Bearing in mind that it was a Conservative government at the time in Britain, which was broadly sympathetic to the coup, or at least on good terms with the military, it was not in their interest to have British citizens getting arrested and getting into trouble. So their motivation was to get us out of the way, out of trouble. And they helped several others apart from myself, to get back to Britain.

TG: What about when you got back to the UK? So how was your reinsertion back into life here? And did the government offer you any kind of support at all?

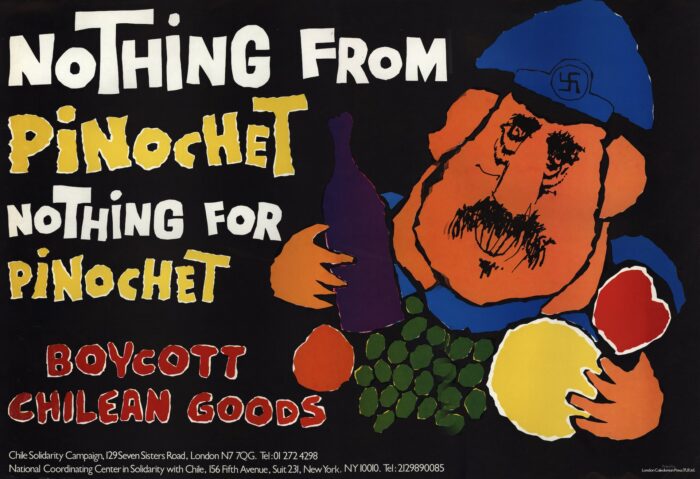

MG: Absolutely not. I made contact, I think, first of all, with Amnesty International, who were extremely active at the time and starting big campaigns. And then with people who were beginning to set up the Chile Solidarity Campaign. So I went to several meetings, there were initial meetings in the House of Commons with Judith Hart, Martin Flannery, Jo Richardson, Ian Mikardo and other Labour MPs mostly on the left of the Labour Party, starting to pull together what would become the Chile Solidarity Campaign.

TG: What did you do in the first days and weeks after your arrival? What was your feeling when you got back? What did you envisage yourself doing?

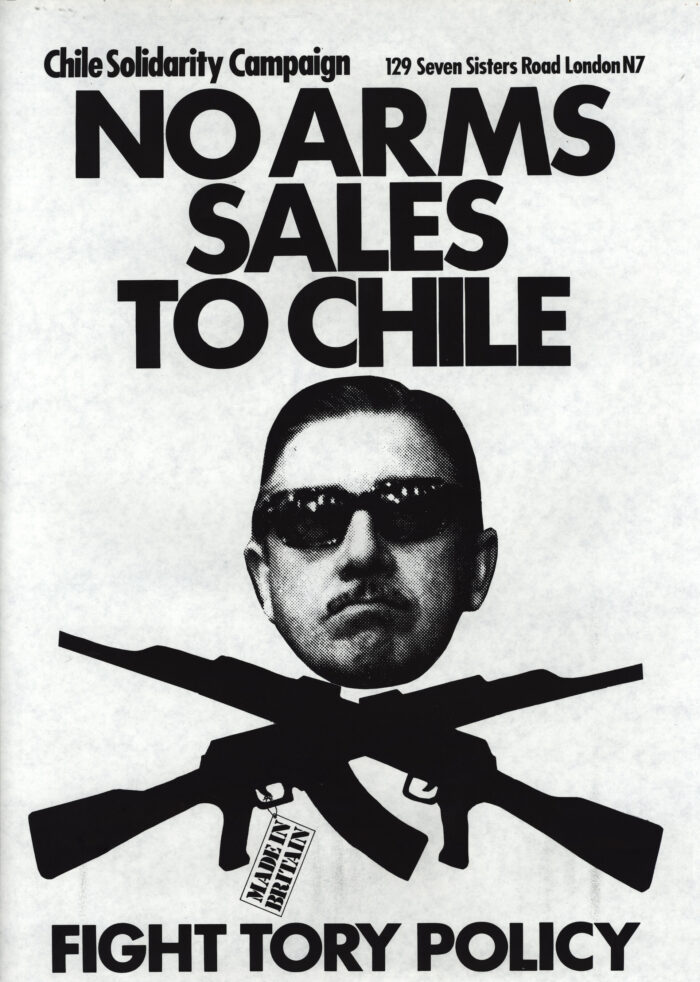

MG: What I was determined to do was to tell my story, because I knew that my testimony was of value to a degree, and to join up with others to oppose the coup and to organise some form of solidarity from Britain. Also to resist or oppose the policies of the British government, which was at the time refusing to accept refugees from Chile and displaying considerable signs of, if not complicity, then certainly acquiescence in the coup in Chile and a determination to resume normal relations with the military government.

TG: What was the attitude of your family, friends and acquaintances when you got back? How did they receive you?

MG: My parents were a traditional Conservative-voting middle class family. They were traumatised by my disappearance. But, at least as they expressed it to me, they were cross with me for having got into a dangerous situation and put them through grief – and they displayed no sympathy at all for people in Chile, what they’d suffered and so on. And that led to not a quarrel, but a breach that I suppose lasted for most of the rest of their lives. I found it hard. Perhaps if I’d been more aware of how they had suffered, during the period when I was missing, perhaps the relationship would have been better. But I found it hard to forgive them.

Others I knew who’d been in Chile had parents who were much more sympathetic. Who were outraged by what had happened, not just to their own child, but to the people of Chile in general.

TG: You talk about them having suffered and gone through this grief and being sort of traumatised to an extent. But what about you? These are the sorts of experiences which can have repercussions for people for years and years afterwards.

MG: One of my friends from university when he met me when I came home said ‘You’ve become so hard.’ I suppose because I had become politically committed both while I was in Chile and then by my experience of the coup and after – something that didn’t seem normal or sit comfortably in cosy middle-class Britain. And it created a breach with him as well. It’s a strange thing how people react.

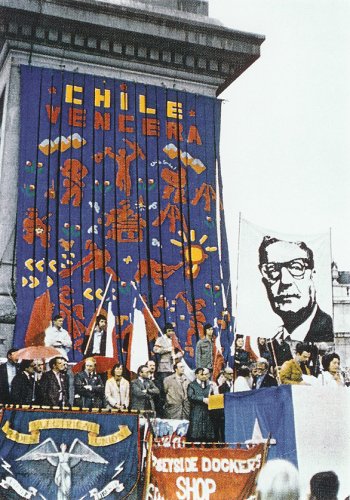

The organisations that came together to form the campaign initially were Academics for Chile and the Association for British Chile and Friendship. Both of those had been set up during Popular Unity in broad support with Popular Unity, and quite a lot of people who were prominent figures subsequently in the solidarity movement – like Dudley Seers, David Lehmann and Judith Hart. There were also artists and intellectuals from London – North London, Hampstead especially. They immediately started taking action.

I think there were demonstrations outside the Chilean Embassy within hours of the coup. People grouped together to help the ambassador who was effectively evicted from his embassy. There were other Chileans who had held posts either in the embassy or in Codelco, the Chilean Copper Company office in London, and some Chilean academics and students who happened to be in the UK at the time.

Some of the younger Chilean students, together with British friends, formed a group called Chile Lucha, which became influential at the beginning and subsequently throughout the campaign. They were very active in supporting the Chile Solidarity Campaign when it was formed and played a positive role.

Most Chileans in the UK, both those sympathetic to Popular Unity and some from groups such as the MIR [Chilean far-left movement, the Revolutionary Left Movement or Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria] which criticised it, agreed that ‘whatever our differences about the causes of the coup and whose fault it was, it makes no sense to replicate that in the solidarity movement. What is in all our interests is to have a united solidarity movement.’

Similarly, within the British broad left and more widely, there was a consensus that it made no sense to have a campaign that excluded, for instance, the Communists or the international Marxist group, the International Socialists (the forerunner of the SWP) or indeed anyone else. And so the campaign was initially – and managed to remain – a genuinely broad left and progressive campaign. It had everybody from the Labour Party leftwards active and more or less in agreement in the measures to be taken in solidarity. And the solidarity was directed not at any one Chilean political party or group, not to the Socialists, not to the Radical Party, not to the Chilean CP, but to Popular Unity and the Chilean people. And that became a sort of founding principle of the campaign.

But beyond the Chile Solidarity campaign there rapidly developed a human rights committee, Chile Committee for Human Rights, with its own staff and office, which took in much broader sectors of the British population, church people, all sorts of progressive people, but who were unaffiliated, who might have felt uncomfortable about more overtly political nature of the campaign. When they started the campaign to adopt Chilean prisoners and some of these subsequently arrived as refugees, the impact was substantial.

Then when Chilean refugees started arriving in numbers, the Joint Working Group was set up to receive Chilean refugees and then resettle them around the country. And this led rapidly to the development and expansion of a network of local committees in 30 or 40 towns and cities across the UK, probably more. We worked also with World University Service because the Labour government diverted the money that had previously gone in aid to Chile to WUS to run a programme for Chilean refugee scholars, academics and students who’d been forced to leave the country either because they’d been imprisoned or because their courses had been suspended, or because they’d been individually targeted. And later on, their children and other children of refugees in Britain who became eligible for refugee scholarships.

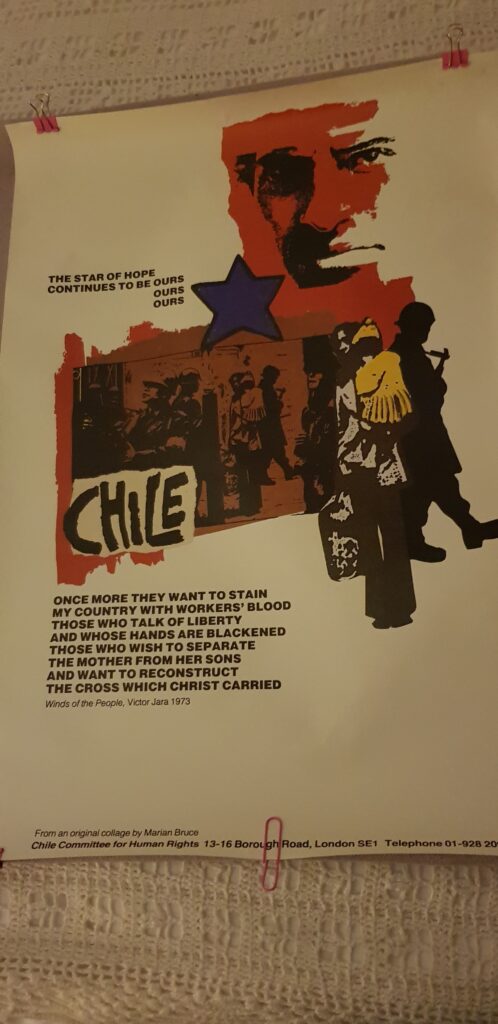

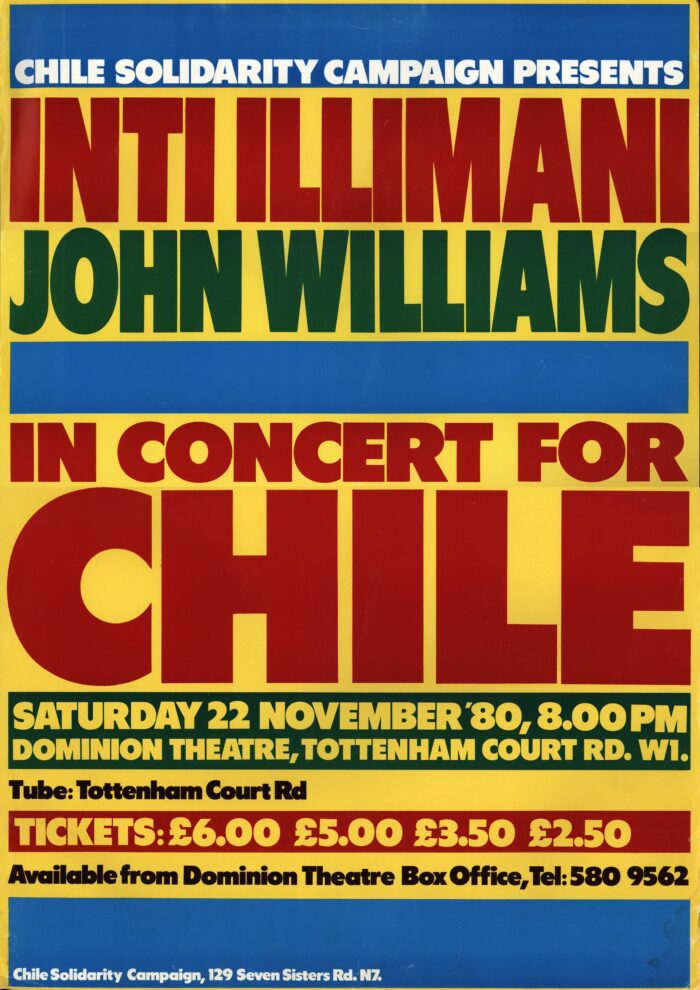

So the campaign itself, together with the Joint Working Group and Chile Committee for Human Rights, became a really broad thing. We also had a cultural committee, which was part of the campaign but quite heavily populated by members of and sympathisers of the MIR, partly because a number of Chilean actors had arrived as refugees who were MIR members. We had our magazine, Chile Fights. Also important were the big concerts with the Chilean groups in Inti Illimani and Quilapayun, both of whom happened to be out of Chile at the time of the coup. With them we filled the Royal Albert Hall on one occasion in London, and big halls in Birmingham, Glasgow, Liverpool and elsewhere around the country.

Because the music was good, catchy, important, committed, it had a huge effect, including on folk music in Britain, which previously had often been rather apolitical. This broadening of cultural work was later expanded by Nicaragua Solidarity campaign during the 1980s to great effect. They were better at it even than we were.

It was in a sense, a whole wide movement with a political range from, let’s say, Lib Dems, Labour and then all the left groups, virtually the whole of the trade union movement.

TG: And can you talk a bit about your role in all of this?

MG: Well, I was employed full-time as joint secretary of Chile Solidarity from roughly December ‘73 until September ‘79. So, six years, and it was an exceedingly full-time job. I probably never worked harder in my life. We had a little one-room office on Seven Sisters Road.

We were greatly encouraged and stimulated by the decision of groups of workers around the UK to boycott Chilean goods or work on Chilean things. Most famously the Rolls-Royce workers in East Kilbride in Scotland, who refused to service jet engines for the Hawker Hunter jets of the Chilean Air Force. Liverpool seamen refused to crew some ships to Chile and put leaflets into the holds of others where Chilean dockers might find them. Liverpool Dockers refused to unload some shipments from Chile. Lorry drivers in Northampton and other cities refused to carry goods coming from Chile, notably fruit and vegetables. The boycotts may not have been economically that significant, but diplomatically and symbolically they were extremely important and gave great strength and reinforcement to our movement.

In 1979 I retired, as it were. But the campaign carried on and grew stronger. It sent several delegations to Chile, including a women’s delegation. It broadened out its cultural work and particularly work by and with women. The campaign had been a rather male-dominated affair, not least because the trade union movement, which was the core of the campaign at the time, was a fairly male-dominated movement. But it broadened out as well. The campaign continued until the time of the plebiscite in 1989, which restored a form of democracy to Chile.

Even after that, the arrest of Pinochet in London in October 1998, while he was being treated for a heart condition in the London clinic, dynamized both the Chilean community and people who’d been involved with the Solidarity campaign. Chileans still in the UK organised ‘El Piquete de Londres’ and they turned up every day outside the London clinic and then another North London hospital and then wherever Pinochet was under house arrest until Labour Home Secretary Jack Straw, shamefully and disgracefully, allowed him to return to Chile.

Pinochet was allowed to return to Chile – allegedly on health grounds – yet when he arrived at a military airport in Santiago, he got out of the plane, out of his wheelchair and did a little dance on the tarmac, waving his stick to denote his contempt for the whole process. That was a sad day.

But his arrest and detention in Britain was tremendously important in Chile. It unlocked a new wave of demands for justice, which had become somewhat stymied under the Concertación governments during the 1990s. The Aylwin government and the judiciary were still afraid of the military. Pinochet, remember, was still commander in chief of the Army until sometime in the late ‘90s. Still a senator. Now his arrest gave some strength to Chile’s courts, who had previously been notoriously pusillanimous and had refused to hear cases because of so-called amnesty laws. The most powerful thing was that for prisoners who were disappeared in their thousands, it was agreed that those responsible could not be covered by amnesty because, in the absence of any proof of their whereabouts or deaths, their cases were still ongoing.

So I would say Pinochet was fatally weakened by the fact of his arrest, despite the fact that he eventually was allowed to return to Chile.

TG: In Chilean politics today, it seems the dictatorship and its legacy are perhaps more present than they have been since the restoration of democracy. You have Boric on the one hand, who’s to some extent set himself up as the torch bearer for this project which was cut off by the period of dictatorship. And, on the other hand, the Chilean right seems to be coalescing behind José Antonio Kast, an extreme far-right figure who’s openly expressed admiration for Pinochet and for the dictatorship period. So why do you think this is?

MG: The estallido social in 2019 brought together and gave hope to a vast panoply of different sectional interest groups, campaigners, and people. Because of the inclusive nature of the subsequent process for drafting the new constitution, and the way in which the constituent assembly worked, my impression is that they drew up a document which was like a vast mixed salad of everybody’s wishes and aspirations. In some ways that was good.

But what it also meant was that there were many, many things in it that specific groups of people were likely to oppose or be concerned about. The result was that when it came to the plebiscite to decide whether this new constitution was going to be accepted, the surprising result was a fairly convincing majority against it. I think the reason could be seen in the very intelligent slogan of the opposition, presumably the right-wing opposition, but a broader opposition, which was ‘Así no’ – ‘Yes, but not like this’. And that was an invitation to everyone who had any minor discrepancy or reservation to vote against it, with an implied promise that there would be another chance for something better later that would satisfy their particular sectional interest.

Be that as it may, the worrying thing is that the new constituent assembly has a heavy majority of the right, including substantial representation of Kast’s Partido Republicano. Perhaps this, too, will maximise opposition. They are going to be pressed by their own right-wing supporters to include stuff about abortion, further toughening or outlawing abortion, gender rights, a whole range of other issues.

[This is exactly what happened, and in December 2023 the ‘right-wing draft’ in its turn was rejected in a national plebiscite by a majority of 56 percent to 44 percent, a smaller margin than that which defeated the first, ‘left-wing’ draft, but still decisive. President Boric subsequently announced that there would be no attempt at a third draft.] .

However, the dissatisfactions which led to the estallido have not been resolved. The Concertación governments after 1990 continued with the same constitution that had been drawn up by Pinochet’s extreme right-wing advisers in 1980, and had remained more or less intact with minor modifications right up to the now, because that constitution is still in effect. A few things have been removed from it, like the provision for ‘life senators’, effectively nominated by Pinochet. They’ve gone. But many other aspects of the Constitution remain in place, in particular, in relation to human rights, and water and other key resources being regarded as commodities to be freely traded

But there was a broader dissatisfaction with politicians, somewhat analogous to the dissatisfactions that led to the Brexit vote in the UK, high votes for populist parties, for Bolsonaro in Brazil and elsewhere – votes by or participation by people who are not fundamentally right wing or at least not ideologically right wing, but have become increasingly disenchanted, disenfranchised, and indeed whose livelihoods have been attacked and fundamentally undermined. And the public services they relied upon have been undermined by neoliberal economics.

Those people participated in the estallido, including some who were extremely violent and trashed a lot of buildings, public facilities, streets, squares and so on, which shocked a lot of people. A lot of people talking now about it don’t remember the progressive things that it was campaigning for, but remember the physical damage. It had effects, comparable perhaps to the Tottenham riots in the UK or wider riots in U.S. cities and in France with the gilets jaunes and so on.

So the estallido was not purely as we’ve tended to view it, a progressive or left thing. It also included substantial, somewhat anarchic elements, and they subsequently have been a negative. I suspect that many of them voted against the draft of the new constitution and some of them certainly have gone on to vote for Kast and his new party, which is called Republicanos. It looks now as though if there were a presidential election, Kast or the candidate for Republicanos might well win against Boric and that they will try to implement a constitutional change, which will be pretty regressive in contrast to the one that was rejected in the plebiscite last year.

TG: You’ve explained this with recourse to contemporary factors. But in Chile it seems like it has this particular historical aspect to it as well. How do you account for that?

MG: I think you need to sort of step back a pace and remember that the coup happened 50 years ago and that the majority of Chileans were not born at the time. And many of them, if they remember the dictatorship at all, were children or young people. The dictatorship ended in 1989. That’s what, 34 years ago?

People on the left, all of the victims, relatives of victims, descendants of relatives, refugees, descendants of refugees have tended to keep the image of and the message of what Popular Unity is about in their minds and in the forefront. But for the majority of Chileans, that’s not the case. They don’t have direct experience or contact with that. So I think that we can’t assume their loyalty or even their knowledge of what Popular Unity stood for or what the dictatorship destroyed.

But for the older generation, especially progressive people, it’s what they hark back to. That period, its symbols and their understanding of what that period was about, really has resonance with a considerable section of the Chilean population today.

Although Kast is indeed extremely right wing, probably well to the right of any of the National Party politicians of earlier decades, he probably isn’t viewed as such by very many young Chileans. I know he has stated his support for the Pinochet dictatorship, but that may not be much registered by people and perhaps a lot of young people say, ‘so what?’.

I think there is another thing happening in Chile, for whatever reason: the rise of mafia-style drug cartels and criminality has been quite dramatic over the last few years. And a lot of people are feeling a profound physical insecurity in their homes, on the streets, in ways that in Chile they were somewhat unaccustomed to. This is common coinage in Mexico or Colombia, or El Salvador, Guatemala, the countries of Central America. But in Chile, it is a relatively new phenomenon. There was always criminality, but not on that kind of gang scale that now exists. And that has made a lot of people frightened. And those people tend to find their sympathies lie more with those like Kast’s Republicanos, who promise hard-line measures.

TG: So paradoxically, the dictatorship is present both for reasons of memory and forgetting. Memory in the sense that the left tends to try to keep the memory alive of those who were disappeared, those who were killed, etc., and tries to reinforce the ongoing relevance of the dictatorship in contemporary political culture. But also forgetting in the sense that, as you were saying, lots of younger Chileans perhaps have no memory of the dictatorship, weren’t personally affected by it, or their families weren’t directly affected by it. So for them it’s past history and perhaps they’re more susceptible to right-wing populist ideas espoused by someone like Kast because they’re not inoculated against it in the way that someone with more of a historical consciousness would be.

Chile was far from the only country in Latin America to suffer the experience of military coup and dictatorship. Others had similar experiences – or even bloodier, like in the case of Argentina, or longer lasting, such as Brazil. There was a genocide in Guatemala with catastrophic loss of life. So perhaps this reflects our own ignorance in the UK and in Europe, but it does seem that Chilean history has had a resonance in the media, academia and in popular culture that others haven’t really to the same extent. Why do you think this is?

MG: There are a number of factors, but one of the most important is the relative unity and coherence of the Chilean left, for many years, even before Popular Unity was formally established. 1970 was the fourth run at the presidency that Allende had, and the Chilean socialists had a long tradition, as did the Chilean CP. And then with the formation of Popular Unity, they created really a very substantial broad left, which I don’t think had any parallel elsewhere in Latin America, certainly not in Argentina, nor in Brazil.

The second reason is the emphasis on a democratic road to socialism, whether we regard it now as having been realistic or idealistic, it was a very genuine attempt. Certainly Allende himself profoundly believed in it, and that had tremendous echoes across Europe. Bear in mind that in the wake of the Second World War, the beginning of the Cold War, there were major attempts with varying degrees of success to isolate the communist parties.

Christian Democracy was publicly touted as ‘The Third Way’, although in Britain that term is more associated with Tony Blair’s New Labour – and there are similarities–. In Chile, the US State Department backed the Christian Democrat leader Eduardo Frei and put money into Frei’s presidential campaigns, probably in 1964 and certainly 1970.

So the Third Way was very important. But of course, it was a non-socialist programme that had relatively minor quarrels with or disagreements with capitalism. It was a project within capitalism, for a more progressive kind of capitalism.

But the socialist alternative within democracy was best expressed anywhere in the world by Popular Unity in Chile. And I think that explains the deep interest in it before 1973, before the coup, and hence the profound reaction that followed.

Think also of the divisions of the left elsewhere, in Argentina for example. The Peronist movement was extraordinarily full of contradictions. Peronism itself had some of the aspects of fascism. Perón spent time in Franco’s Spain and was quite pally with Franco at various times. And yet the Montoneros, the left-wing of the Peronist youth, were guerrillas who espoused the more militant forms of Cuban-exported revolutionary socialism. So it was quite difficult to be in solidarity with the Argentine left because it was very difficult to say what it was.

The other thing that’s important is the Cold War, and that by the end of the 1960s, the Cold War consensus and in particular the division of the World Trade Union movement was beginning to fall apart, partly under the impact of the Vietnam War, partly under the impact of the behaviour of American trade unions and the AFL-CIO, its close alliance in many cases with CIA sponsored think tanks and projects and the growing awareness of this in the European Trade Union movement.

Even in the Brussels-based Trade Union Internationals like the International Transport Workers Federation (ITF), many were no longer willing to be dictated to by this Cold War rhetoric. Chile was a good opportunity for them to identify with a movement much closer to their own heart. And when that movement was destroyed by the military, to react in a very direct way.

Certainly I think this explained the actions of people like Jack Jones, the General Secretary of the Transport and General Workers Union, Hugh Scanlon of the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers (AUEW), and many other leading British trade unionists. And they saw Chile not just as important for Chileans, but also important for them. And they used the Chilean experience to try to steer the world trade union movement away from Cold War divisions and direct alignment with US interests.

One of the things that’s important in Chile at the moment is the whole issue of impunity. President Boric has promised a new commission to search for the bodies of the disappeared prisoners. Impunity tends to be focused upon the victims of the military coup and the perpetrators in the military.

But I feel that there is much more important impunity that is still not being touched even by Boric and the more progressive sectors in Chile. And that is the impunity of wealth. Those sectors of wealth that backed, sponsored, stirred up, provoked and made possible the coup in Chile, which backed the dictatorship subsequently, and are still alive and well and breathing and if anything, gaining strength in the US and here in Britain.

Until we begin to tackle the impunity of wealth, we will not have the possibility of a progressive and socialist future for any of us.