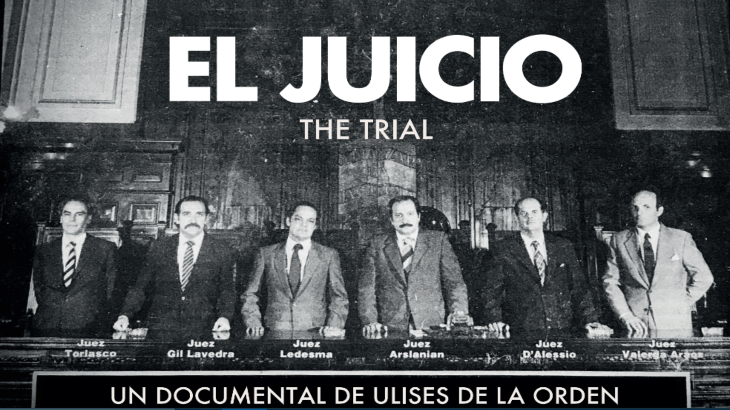

This new documentary by Ulises de la Orden takes us to the heart of the courtroom using original footage from Argentina’s post-dictatorship trials. The film screened at Open City Documentary Festival at Bertha DocHouse in September 2023.

Commonly referred to as the Trial of the Juntas, this case involved the prosecution of nine members of Argentina’s de facto government, who were responsible for gross human rights abuses during the dictatorship from 1976-1983. Up to 30,000 people are believed to have been killed during the dictatorship, many of them forcibly disappeared.

In 1988 the judges took copies of video tapes of the trial to Oslo, where they were stored by the Norwegian government. The original footage remained unbroadcast for decades, until human rights organization Memoria Abierta set about digitizing and preserving the tapes.

2022 saw the release of Argentina, 1985, a fictional depiction of the trials, but de la Orden takes a different approach; condensing the 530 hours of video tapes into three intense hours, divided into 18 chapters. To create the final edit, de la Orden and his team spent months fine-tuning until they had crafted a carefully-constructed narrative. The final version was the 22nd edit. Deliberately compiled in a non-linear fashion, El juicio’s sequences don’t necessarily follow the chronology of the trial but serve to create a dramatic narrative.

The forces of good and evil

There is a clear distinction between the characterization of the defendants and the witnesses, and throughout the film protagonists and antagonists become increasingly obvious. Shots of the defendants (amongst them military officers and dictators, Jorge Rafael Videla and Emilio Eduardo Messera) show them nonchalantly smoking and reading newspapers during the horrifying and detailed witness testimonies. When they enter or leave the courtroom, they smile and greet each other. They uphold the belief that the “Dirty War” was justified and deliberately avoid questions to draw out the trial process for as long as possible.

In contrast, witnesses are filmed from behind whilst the viewer sees the reactions on the judges’ faces (it’s not clear whether this was an artistic or legal decision by the courtroom’s camera operators). The juxtaposition of this seeming anonymity with the raw, emotive testimonies (of which there were 280) creates a powerful oppositional force to the bench of defendants. In a particularly harrowing sequence, several female witnesses detail the torture and sexual assault they either endured or witnessed. This is made all the more compelling by jump cuts which stress the extent of the crimes committed. This form of dramatic narrative isn’t native to factual filmmaking, but it gives a voice to the disappeared and highlights the need for justice, no matter how much time has passed.

Representing the truth

In the Q+A that followed the Open City screening, De la Orden pointed out the importance of the work being true to the victims and their families, to himself as a filmmaker, and to Argentina’s history. During the editing process, subjects of the film (including witnesses and judges) were consulted and shown rough cuts. By integrating the subjects into the filmmaking process, they became active participants in documenting their own stories and shaping the narrative of the final cut. When the footage was originally broadcast on Argentinian television, it was only allowed to be shown in three-minute excerpts with no audio or subtitles. This means that El juicio will be the first time that most people have witnessed the trial footage. Within this context, it’s essential that the original witnesses, prosecutors, and judges helped to shape this landmark work.

Nunca más

Nearly 50 years later, the legacy of the dictatorship still lives on. In 2022, 19 former military officers were charged for crimes against humanity committed during the dictatorship. The epilogue details the trials that are still ongoing, with many suspects still at large. In Post-dictatorship societies often ask: how do we remember? Perhaps El juicio will serve as an example. It is likely that other reconstructions and edits of the trial tapes will begin to appear now that the archival footage is recovered. De la Orden’s dramatic retelling may not be chronological or completely faithful to its original form, but it documents a version of the truth that has gone untold for decades.

El juicio can be streamed online at KINOA.TV

You may also be interested in… Clamor: The search for the disappeared of the South American dictatorships by Jan Rocha.