- At least 177 environmental defenders were killed last year globally, according to a new report from Global Witness. At least 155 of them were in Latin America.

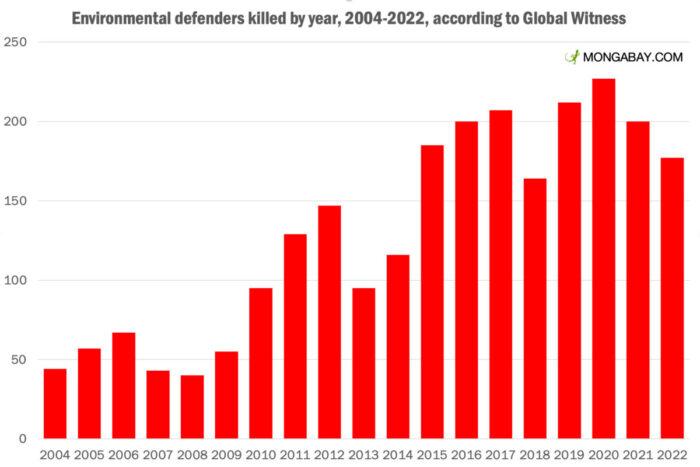

- There have been 1,910 murdered defenders since 2012, the year that Global Witness started tracking this type of violence. Last year, the murders took place across 18 countries worldwide, 11 of them in Latin America.

- Colombia topped the list with 60 murders while Brazil came in second with 34. Honduras led the world in murders per-capita with 14.

- This article was first published on 14 September 2023 by Mongabay. You can read the original here.

Latin America is far and away the most dangerous place for people fighting to protect the environment. From activists and community leaders to journalists and politicians, standing up against deforestation, pollution and other threats to the environment results in death more than anywhere else in the world.

At least 177 environmental defenders were killed last year globally, according to a new report from Global Witness. At least 155 of them were in Latin America — a shocking 88% of the year’s total. Global Witness said those numbers could get worse in years to come.

“The worsening climate crisis and the ever-increasing demand for agricultural commodities, fuel and minerals will only intensify the pressure on the environment – and those who risk their lives to defend it,” the report said. “Increasingly, non-lethal strategies such as criminalization, harassment and digital attacks are also being used to silence defenders.”

There have been 1,910 murdered defenders since 2012, the year that Global Witness started tracking this type of violence. Last year, the murders took place across 18 countries worldwide, 11 of them in Latin America.

Colombia topped the list with 60 murders, nearly double what it had in 2021. Brazil came in second with 34 murdered defenders, a slight uptick from the 26 it saw the previous year. Mexico had 31 murders, a major decline from the 54 in 2022.

Honduras led the world in murders per-capita with 14.

The motivations for the violence weren’t always clear. The report found that 10 of the murders were connected to agribusiness while another eight were linked to mining and four to logging. But in five instances — all in Latin America — the victims were children.

More than a third of all murdered defenders were Indigenous, highlighting a problem that is especially prominent in the Amazon rainforest. More than anywhere else in the world, Indigenous groups there faced extreme pressure from legal businesses and criminal groups alike, all interested opportunities for mining, logging and agriculture.

The violence made global headlines late last year when Indigenous activist Bruno Pereira and his colleague, Guardian journalist Dom Phillips, were killed in Brazil’s Vale do Javari region in the western Amazon, an area where criminal groups, Indigenous people and other traditional communities clash over control.

In Pará, Brazil, the Kayapó people have experienced escalating violence amid a new influx of mining caused by stripped-back regulations. Similar mining-related violence is taking place in Venezuela to the Uwottüja and Yanomami peoples and in Peru to the Kakataibos and Shipibo-Konibos peoples, the report said.

“Why do we want to protect the territory and risk our lives for it? We are not the only ones who need the forest to survive, we have to fight alone, but we do it for the entire planet, we do it for our children and for our grandchildren, so they can live in peace,” said Bepdjo Mekrãgnotire, a leader of the Kayapó people in Brazil. “We will keep the forest standing, we will protect the air, the rivers, the fishes, the animals. This is what we fight for.”

Policymakers have taken some steps to address the violence. The first annual meeting of the Escazú Agreement, created to protect environmental and human rights defenders, was held in Chile last April. The first UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders also took office last June with a mandate to enforce countries’ obligations to protect environmental activists. Anyone receiving threats can now submit complaints to the special rapporteur.

The E.U. is also considering supply chain regulations, known as the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, that would require companies to carry out thorough due diligence measures to help avoid human rights and environmental violations connected to their imports. It’s expected to receive approval by the end of the year.

At the same time, Global Witness said countries need to continue developing new strategies for creating “safe environments” for defenders and take the lead in investigating violence against them. Businesses also need to identify and prevent violence connected to their products.

“Urgent action is needed to hold companies and governments to account for the violence, criminalization and other attacks faced by land and environmental defenders as they seek to protect their land, their communities and our planet,” the report said.

Banner image: The Indigenous communities that live in the Amazon are subject to threats during the invasion of their territory. Photo: Cícero Pedrosa Neto / Global Witness.