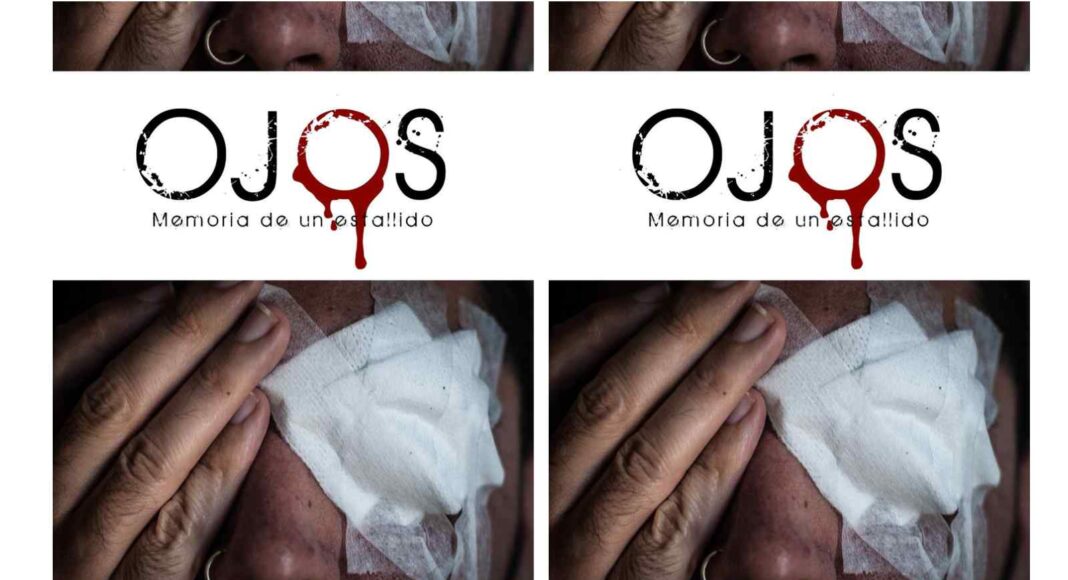

Ojos: Memoria de un estallido is a book put together as a memorial for victims of eye trauma suffered as a result of the fight for human rights in Chile. The people whose stories are gathered in this volume were caught up in the so-called Estallido Social, a period of social unrest which occurred between October 2019 and March 2020.

The Estallido began in Santiago de Chile when secondary school students instigated a fare boycott on Santiago’s metro system to protest a recent hike in public transport prices. The authority’s crackdown on the students led to sympathy marches across Chile fed by widespread popular dissatisfaction with the high cost of living and a general loss of faith in the political classes. What began as a small, local movement soon developed into nationwide civil disturbance.

The measures imposed by the government in response to the protests and unrest led to some of the worst violence in Chile since the time of Pinochet’s dictatorship. A state of emergency was declared and enforced with violence: tear gas was used to disperse crowds and protesters were fired on by the police and army, resulting in a huge number of civilian casualties, including 15 deaths.

Amnesty International documented the extreme cruelty and disproportionate use of force by the authorities in its ‘Eyes on Chile’ report which stated that the action of the authorities meets criteria for defining torture. Evidence for this is seen in the sheer number of injuries reported: from the start of the unrest in October until 30 November, 12547 wounded were admitted to hospital emergency departments, there were 1080 gunshot injuries and 347 eye injuries. Indeed, several of the stories in Ojos: Memoria de un estallido contain accounts of the authorities purposefully causing injury (e.g. p. 8 and p. 60).

The high rate of eye injury is almost certainly a direct result of the Carabineros’ (Chilean state police) use of rubberised buckshot, a form of non-lethal ammunition that nevertheless pierces flesh and causes extensive damage. The use of rubberised buckshot was not limited until its exact nature was made public, at which point, the number of eye injuries had already exceeded 250.

This collection includes 17 stories and these are accompanied by 18 images to complement the narratives. The experiences of several of the contributors to this volume were highlighted by Amnesty as particularly egregious examples of human rights abuses; their stories and the others contained in Ojos de Memoria are gruelling reading. However, this is as it should be. The accounts range from straightforward narrative to more cryptic psychological pieces to poetry, and the editors have successfully arranged these diverse voices into a coherent whole. Each voice is separate and distinct but their stories weave a detailed tapestry telling a broader narrative about Chilean society.

The images included with the stories have undoubtedly been well chosen to reflect the individual characters who contributed to this book. There are photographs from the riots, pictures of the authors and their injuries, as well as some very moving hand-drawn artwork either by the authors themselves or their children. These images work well with the text, providing what feels to be a very personal link to the contributors.

The sheer horror of the injuries suffered by the book’s contributors is obviously most striking and the trauma they have been through as a result is clear. People have very different responses to trauma: a few make only metaphorical references to their injuries, for instance speaking about being ‘rota igual que una hoja de papel’ – torn like a piece of paper (p. 36) while several authors speak of their lucha and even seem to make light of their injuries ‘Quedó con medio cráneo y epilepsia, pero la lucha sigue’ – I ended up with half a skull and epilepsy, but the fight goes on (p. 34). One author speaks of their guilt for being an added burden to their families and how they have felt the need to lie about their pain to protect others (p15-16) while another, talks with ferocious anger of how the state ‘me cagaron la vida para siempre’ – they’ve crapped up my life forever (p. 64).

The lack of support from the government, however, is a common theme contributing to the desolation expressed by many of the book’s contributors. One author describes how they could not stay in hospital after their injury because they couldn’t afford the bills (p. 47) and another describes how promises of help were made but have never materialised (p. 82). Even more disturbingly there are accounts of state intimidation of injured protestors (p. 17) while another contributor describes how ‘discursos de odio’ narratives of hate (p. 64) have been deployed against those involved in the protests constituting a double victimisation for those who were injured.

Several of the pieces included in this anthology give us details of their author’s back-story explaining about the hows and whys of their involvement in the Estallido. Contributors speak of numerous common social problems such as difficulties getting medical care for relatives (p. 30) or struggling to get an education (p.53-54). As one author attests: ‘In Chile you pay through the nose for everything: to get good healthcare you have to pay to go private, the public system has collapsed, the waiting lists are interminable, and often, surgery never happens because the person dies first’ (p. 57). This terrifying yet matter-of-fact statement sums up the extremity of the situation faced by many Chileans.

While there is less fear of being disappeared for saying the wrong thing, this has been replaced by political indifference and the cruelty of an economic system that further impoverishes the needy.

A striking feature of many of the stories in this collection is the despair at how Chile’s post-dictatorship society has failed the people. Of course, Chile’s political climate is not quite the same as it was, and several contributors contrast their experiences with the political oppression of their parents’ generation — one comments that his elders often tell him ‘“si hubieses sido grande en la dictadura te hubiesen matado”’ – if you’d been an adult during the dictatorship they’d have killed you. However, while there is less fear of being disappeared for saying the wrong thing, this has been replaced by political indifference and the cruelty of an economic system that further impoverishes the needy.

What is more, when the people manifest their frustration, it is as if nothing has changed; rather than facing up to Chile’s social and economic problems, the State reverts to the tactics of authoritarianism, seemingly forgetting all the promises that the atrocities of the dictatorship should never be repeated. And this is exactly what happened in the Estallido, as one contributor says: ‘During the Estallido, I thought of the saying I grew up with: “Never again in Chile”, a saying that’s never been really meant because I saw how we were repeating that bloody history and it was my turn to live through it.‘

A few authors give their occupations and ages and from other information contained in these stories it is clear how broad a cross-section of Chilean society was involved in the Estallido. Not only are the poor and marginalised represented here, but there are also professionals and high school students whose accounts underline not only how the dissatisfaction with Chile’s political and economic regime crosses class and race divides but also the immense solidarity of Chile’s people. Several contributors describe how they went to the protests with friends, work colleagues, and family and how they were entirely peaceful events — until the police turned up. Their descriptions of how strangers comforted and administered first aid when they were injured and even helped them get to hospital, are deeply moving. Yet these accounts are also fundamentally distressing in how they underline the deep “Them and Us” divide that seems to exist between the people and those in power, with one contributor commenting: ‘sólo el pueblo ayuda al pueblo’: only the people help the people.

This book fulfils its purpose as a meaningful memorial to the people so grievously injured in Chile’s most recent political violence. It does this primarily in the way the stories it contains demonstrate the incredible survival drive of those affected and the solidarity of the Chilean people, and secondly in how it is a demand for justice from the Chilean government. The anthology also acts as a powerful indictment of the Chilean government for allowing the conditions that provoked the riots, ignoring the inhumane actions of its own law enforcement, and, in the aftermath, failing to provide help and compensation for those injured.

You can download ‘Ojos: Memoria de un estallido’, written in Spanish and edited by Natalia Aravena, here.

Hebe Powell is a freelance academic and literary translator (Spanish to English). Hebe is also a researcher in variational Spanish pragmatics focussing on politeness theory and rapport management in online communication. She lives in London with her husband and two children.