This review is reproduced from Amazônia Latitude, where it was published on 28 November 2023. You can read the original here.

In 1820, the naturalist botanist Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1794 – 1868) and the zoologist Johann Baptist von Spix (1781 – 1826), German scientists, took from the heart of Brazil to Munich, Germany, several souvenirs collected on their scientific expedition across the tropics: 6,500 plants and seeds, 2,700 insects, 85 mammals, 350 birds, 150 amphibians and reptiles and 116 fish, in addition to two enslaved indigenous children: the girl Miranha and the boy Juri.

This detail of the famous scientific expedition of Spix and von Martius has always been treated as a mere detail to be appreciated with the rules of historical resignation: they took six indigenous people captive from the Amazon, people who had been given as gifts or were exchanged for equipment in their villages. Of these individuals, two were left in Brazil with authorities at the time, two died during the crossing of the Atlantic, and with the two children they disembarked in Lisbon, from there heading to Madrid, then Valencia, Tarragona, Barcelona, up the Pyrenees, passing through Perpignan , Lyon, Alsace, entering Strasbourg, bordering the Rhine and finally arriving in the capital of Bavaria, the final destination of these two souls. The boy would die six months after arrival. The girl, Iñe-e (renamed Isabella Miranha), twelve months later.

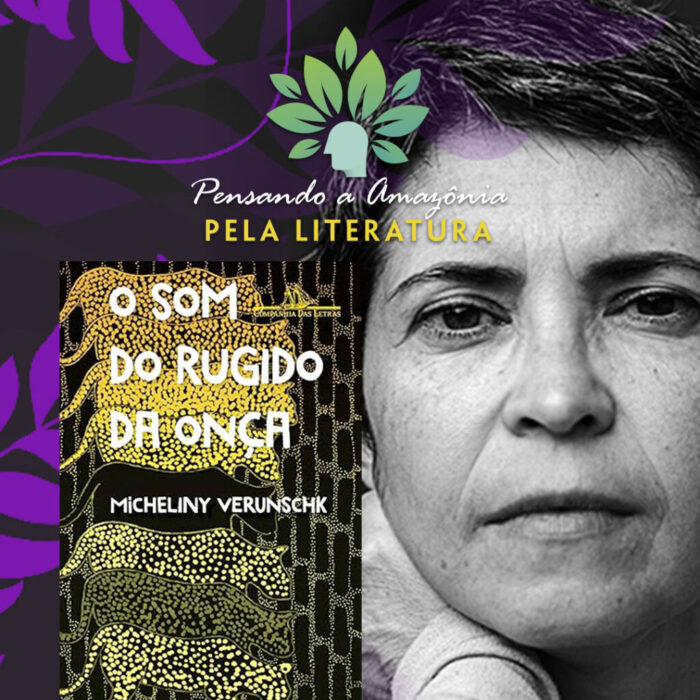

Until, in 2021, Pernambuco writer Micheliny Verunschk decided that it was in the interest of future stories to revisit the memory of the experience of the smuggled girl Iñe-e and, finally, pair her point of view with those of her captors, who enjoyed, in their time and ahead of him, of formidable dissemination and analysis. But Micheliny did not have the same tools available (notebooks, scientific documents, epistolary files, the arsenal of written language) – “paper supports anything you want”, thought von Martius in 1820. However, the author of The 21st century had an equally powerful weapon: the flexibility of literature. Literature is that quality that Roland Barthes highlighted: that of giving knowledge an indirect place and, consequently, a precious place.

It is this kind of mediumistic impulse that feeds “ O som do roar da onça ” (Companhia das Letras, 2021), one of the most acclaimed and successful novels of recent years. “Iñe-e is lent this voice and this language, and even these letters, all very well arranged, arranged one after the other, like a necklace of ants on the floor, because now this is the only means available”, he warns the author, in the first part of the book. “When Iñe-e died, she was twelve years old. So, that’s the dead girl’s voice.”

But the voice of the dead indigenous girl is not the only one, there is an evocation of testimonies from two worlds in the book. Between the past of 200 years ago and the author’s own voice, which proudly merges with that of her character, there is a chorus of voices that pushes our consciousness forward, to the São Paulo of violent climate change, streets turning into rivers, the pioneer affirmative clash of chief Raoni and the struggles of original peoples, the feelings of Josefa, an expatriate from Belém do Pará living in the hustle and bustle of the metropolis, the murder of a black councilor in Rio de Janeiro, the polyphony of collective responsibilities, the debt to with our own history. “My maternal great-grandmother was caught by a lasso, did you know that? I have a lot of Kayapó blood in me. But the fact is that everyone has a grandmother in Brazil, me, you, the doorman down there.”

These voices differ due to the rhythm of the narrative. In the stories dreamed up through cosmogony and the destinations of spirits – the girl Iñe-e was destined to be a healer of the body and spirit after her encounter with the great queen of the forests, the jaguar -, Micheliny approaches Rosean language , of the inventions of that language that already exists freely in nature, but needs a good ear, an ear that can hear the noise of a game animal drowning in its own blood. “None of them had ever seen a river that spoke so many waters, rivers without banks.”

The genocide of colonization, Micheliny points out, did not end in the extermination of bodies and cultures. He projected himself into the consciousness of the times, and that is why the batteries of enlightenment and rescue must be aimed. “Expurgating, diverting, eliminating variation becomes a habit for those who write or rewrite history, especially the history of others, but every scrape or blot, every pitch cloud that covers the drawing or the first writing leaves its mark, its trace elements”. The excerpts from the “scientific” judgments of the Spix and von Martius expedition, included in the narrative, lead readers to the conclusion of its malignancy:

“The Indian’s temperament has hardly developed and can be described as phlegmatic. All the powers of the soul, even the noblest sensuality, seem to be in a state of torpor. Without reflecting on universal creation, on the causes and the intimate relationship of things, they live with thoughts concerned only with their own conservation. Past and future are almost indistinguishable for them, which is why they never worry about the next day. Strangers to every feeling of deference, gratitude, friendship, humility, ambition, and, in general, to all the delicate and noble emotions, which distinguish human society; insensitive, taciturn, immersed in the most absolute indifferentism towards everything”.

Literature can have intention, literature can have responsibility, literature can have a target (“No other man would stand, because he knew well that the male belongs to war in the same way that war belongs to the male”), literature can Be whatever you want, but it will have a very short life if it doesn’t have rhythm, cadence, drive. And the choreography is precisely one of the great achievements of Micheliny’s work, what makes her dance unscathed amidst the political diversity of her reader in post-coup Brazil, the idolatrous reader and the consumer reader. “His beautiful words were written on the white man’s tomb, Among the palm trees I always feel young. In their midst, I rise again. But, to do so, he would have to be a jaguar, something that, no matter how hard he tried, and he didn’t even try, he would never be. It was over, hunting was it.”

Defying the rules of the traditional historical novel, Micheliny Verunschk aligns herself with greater joy alongside the historical revisionists of contemporary pop culture, that kind of Tarantinian daring that has the courage to incinerate Hitler during a movie session, make a slave return to the lands of his captor to settle accounts with a past of servitude or stop counterculture killers from executing a pregnant woman in Hollywood. The message is symbolic: one way or another, it is necessary to come to terms with the past whose voice was stolen. “You learn that bad things don’t end, they don’t end with everything they did before they came into the world, much less with what they did to you and your companions, nor will it end after what they did there with Kaiemi, the daughter of your father’s son, passes. brother, don’t even put an end to what they did to your people with the Boros, the Huitotos, the Huni Kuins, the Spider’s greed for taking their lives”, says a character.

The author is a literary reality that has established itself over the last 10 years. Micheliny Verunschk Pinto Machado’s first novel, “Our Teresa – life and death of a suicidal saint” (editor Patuá, 2014), was distinguished by the Petrobras Cultural Program and won the São Paulo Prize for best book of 2015. Master in Literature and Literary Critic and PhD in Communication and Semiotics from PUC São Paulo, she subsequently published the books “Geografia Íntima do Deserto” (Landy, 2003), “The movement of birds” (Martelo Casa Editorial, 2020), this “O som do roar da onça” (Companhia das Letras, 2021, and winner of the 2022 Jabuti) and now his book of short stories “Desmoronamentos” (Martelos Casa Editorial) which won first place in the 2023 National Library Literary Prize.

Text and production: Jotabê Medeiros

Editing: Emily Costa

Art and website assembly: Fabrício Vinhas

Direction: Marcos Colón