This is the first issue of LAB’s new series of guest-written quarterly dispatches, available exclusively to our patrons (paid subscribers). Each issue of Voz will bring you a long-read article conveying the experience and analysis of our partners out in Latin America – activists, journalists, artists and academics. We hope that their in-depth testimony and commentary will help broaden our understanding of the region, and through it, the world.

Our first guest writer, Natalia Aravena, is a Chilean psychiatric nurse whose right eye was destroyed by a tear gas grenade thrown by Carabineros in the country’s recent estallido social, and has become a prominent campaigner on behalf of all who were injured in the demonstrations.

Natalia describes how, while she was still at school, she and her fellow-students determined to break out of their ‘bubble’ of relative privilege and join the protests; how these became an avalanche of demands for fundamental change – an end to the neo-liberal economic model which has brought savage inequality to her country; and how this led to a landslide plebiscite approving the demand for an entirely new constitution for Chile to replace the one imposed by the Pinochet dictatorship.

In the resulting elections for the Constitutional Convention, in May 2021, Natalia decided to stand as a candidate in Peñalolen, the poor area of Santiago where she grew up. She won in her district but, as she explains, an ironic side effect of the gender parity rule meant that she was not in the end elected.

She recalls in painful detail the day she was injured and her determination to continue the fight: ‘We’ve witnessed how the same themes are repeated – the powerful seek to appropriate for themselves the resources that belong to all of us on this earth. I hope this can be the start of Latin America’s liberation.’

This issue was translated by Mike Gatehouse. If you’d like to read the original article in Spanish, click here.

On 18 October 2019, I was working my 8am – 8pm shift as a nurse in a psychiatric clinic. All week there had been demonstrations at the metro stations protesting the fare rises, and this was the final day. It was lunchtime and on TV we could see the demonstrations were still going on and people were filling the streets of Santiago. Similar things were also starting to appear in other cities. I remember feeling really happy, thinking ‘At last we’re rising up, we’re not putting up with any more abuse’. On the other hand, we were a little afraid, because recordings had begun to spread on WhatsApp and social media, saying that the military were going to take over the streets, that they had orders to shoot, that they would impose a curfew and it would be like it was during the military coup of 1973. Nevertheless, the main feeling was one of hope, that at last ‘Chile has woken up’.

I’ve spoken to a lot of people about it and we all agree on feeling a sense of relief that day. There was a collective longing to do something about inequality, but also this idea that we Chileans are passive, prone to keep shtum in the face of injustice. However, the secondary school students jumping the metro turnstiles and rebelling gave us the strength we needed to fight against oppression.

Learning inequality

Ever since I was little I’ve had class consciousness and empathy with others. I was born and grew up in Peñalolen, a borough in the south-eastern part of Santiago, in a house with two rooms – really small considering there were six of us. Peñalolen is one of the boroughs with the most inequality between its different neighbourhoods. There’s a stark contrast between the Alto Peñalolen area, close to the mountains, where people from the wealthier classes live, in houses that cost at least 400 million pesos [around £385,000]; and the Lo Hermida and La Faena areas, where there were old squats 1)A toma in Chile is a squat – the seizure and occupation of land. Many of the poorer areas of Santiago began as squats, dating from the 1960s-70s, where pobladores would move into a vacant piece of land, often at night, plant the Chilean flag and erect callampas, shacks of wood and cardboard. Evictions were often violent. Those that managed to survive and stay put would gradually transform their población, erect permanent buildings, get connections to water, electricity and drainage, and obtain legal recognition from the authorities – at least until the military dictatorship put a stop to it. and settlements with precarious or illegal status. My house was in the San Luis area, a neighbourhood on the border with Macul and La Florida, with a mix of middle and lower class inhabitants.

I grew up with my parents and my three brothers. My mother is a housewife and comes from a family of seven children, who didn’t have enough money for her to finish her secretarial training. She got pregnant with twins at 19, married her partner and had my third brother by the time she was 24. A year later, her husband decided to go abroad. So my mum was left on her own in a house with three children. A few years later she met my dad and they got married. When I was born, my brothers were already 15 and 10, so I was the spoiled one; the only girl and the youngest. My dad is an engineer, the first member of his family to become a professional. They were a poor family. My granny had to turn the cuffs and collars of their shirts when they wore out and darned their socks, and my aunt slept on the ironing board because they didn’t have enough beds. My dad always says that he only got into university by chance: he had a way with numbers and sat the entrance exam just to see how he would do, never thinking that he would do well enough to get in, to be able to study and apply for a student loan —which meant he would end up in debt for many years.

I went to school just opposite my house until I was 10. I had lots of friends at that age who I now realise were living in very precarious conditions: they had nits, didn’t wash much, and some were victims of psychological abuse. The mother of one of my friends taught in that school and she appeared years later on TV because she had tied a girl in her class to her chair with adhesive tape and hit her. My mum says she often heard teachers shouting at the children from our house.

After that, I went on to secondary school in the borough of Macul. It was a Catholic school, semi-private, which means it was private but got financial support from the state, so the fees weren’t too high and middle-class families could afford to send their children there. You didn’t see so much poverty, but I remember when I had just started there, a child and his group of friends started to bully me. When my mum told my teacher about it, he explained that the child had problems at home and that he was mistreated. His father had left home and he himself often had to stay at home to look after his younger brother.

The ‘bubble school’ rises up

In 2011, major student unrest broke out across the country. I was 16 and in the third year of middle school. We started to talk in our classes about how other schools and lycées were getting politically organised, but not us. Why not? We began to question our privileged backgrounds and the fact that many of us would go to university because we were getting a relatively good education simply because our families could afford it, but that lots of children came from families that couldn’t pay and were forced to study in state schools 2)Educación municipal means ‘state schools’, dependent on the municipio or council, in the way schools in the UK are (or were) run by the local education authority. most of which had pretty poor standards. We questioned why we could sit the University Entrance Exam (PSU), an exam which only tests specific types of knowledge: logical, rational thinking and scientific-humanist thought — which excluded a broad group of students who couldn’t meet those standards — the same situation which meant that my dad could go to university, but not his brothers.

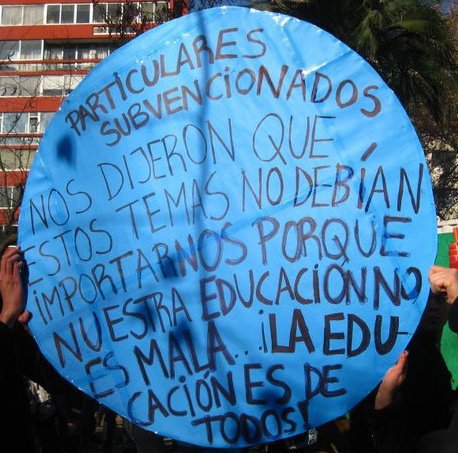

We began to protest, like the ‘penguins’ 3)The ‘Penguin Revolution’ or ‘The March of the Penguins’ was so-called because of the appearance of thousands of school students marching in their school uniforms. in the student revolution of 2006. The priests and school authorities opposed what we were doing, as did many of the parents. We ended up describing ourselves as a ‘bubble school’, where there’s talk of charity and loving your neighbour, but where everything takes place within a comfort zone, inside a ‘bubble’. So a large group of us secondary students from the school went out on a march for the first time, with a sign depicting a bubble, to demand quality education for everyone.

I went on various marches in those years and there was one constant pattern. We would arrive at the assembly point for the march and begin to move forward. Along the way we did congas and dances, we chanted and expressed ourselves in a whole range of beautiful art-forms. But when we got to the end point, the Carabineros [Chilean police] would appear with movable barriers, and begin to disperse the marchers with tear-gas trucks and water cannons. Most people would begin to disperse and the march would end. When we got home and put on the TV, we’d see all these images of destruction and vandalism, of police persecuting secondary school students, but that was it. There was nothing about the thousands of people who had come together, marched, danced; only images of destruction which we knew were only a small percentage of what happened on the march.

Now I can understand why our parents, including my own, were so afraid of us going out into the streets. They had lived through years of curfews; of the pervasive threat of Carabineros and soldiers in the city, rifles at the ready; of having to burn their own books and any kind of evidence suggesting opposition to the dictatorship. If they said anything ‘unwise’ in the wrong place, they might end up being ‘disappeared’ forever.

Nevertheless, and this was the general sense of it, my generation had grown up without this fear, and with a lot of anger at seeing our parents subjected to such grinding poverty. The neoliberal model has taken root in our country and this has meant that a few powerful people continue to enrich themselves more and more, at our cost; the cost of our lives.

In Chile, everything has to be paid for. To get access to decent healthcare you have to go through the private system and pay because the public health system has collapsed, the waiting lists are unending, and you never get an operation because you die before you get there. Health professionals offer poor service because most of them have to work in precarious conditions and suffer from burn-out; medicines are extremely expensive, especially those for mental illness. Schools are expensive and the free ones are, for the most part, of a really poor standard, so it’s extremely difficult for a child from a state school to get into higher education. Higher education is even more expensive than secondary school and the admissions system via the present University Entrance Exam (PTU) is highly discriminatory. My generation has seen our parents unable to study because they couldn’t afford to; working a lot, sometimes having two or three jobs at once and yet earning so little; living in debt, with the interest constantly mounting up; spending hours on public transport to reach their place of work. Living just to work, with nothing besides.

Chile wakes up

The reason I began to go out and demonstrate is because everything around me as I was growing up reminded me that life in Chile is profoundly unfair. I consider myself privileged because I have never had to live in need. I could go to university without having to work at the same time, I’ve been able to access healthcare, and I’ve never gone hungry… but that’s not the case for most Chileans.

Living through the estallido social 4)Estallido social (social outbreak or uprising) is the term now widely used in Chile to describe the steadily growing wave of protests, marches, demonstrations and direct action which perhaps began with the secondary school students’ ‘Penguin Revolution’ around 2006 and has continued and grown ever since, culminating in the referendum that launched the present process to draft a new constitution. has changed my life completely. I feel that I, like many others, was very content in my ‘comfort zone’. Often I think the teenage Natalia would have been disappointed in me because I left that period of activism behind me and joined the daily grind. Every now and then I would join in a demonstration or solidarity action, but all the time I felt I wasn’t doing enough to change the world, as I had promised myself I would do while I was still at secondary school.

So, when the uprising began, I joined in immediately. On 19 October I got home in the morning to sleep because in the end I’d had to stay on shift for 24 hours, because public transport in Santiago was suspended. Once rested, I went out into the street to join in a caceroleo 5)A caceroleo (pan-bashing) is when people go onto balconies or into the streets, bashing pots and pans with spoons to make a cacophony of protest, with empty pots symbolising hunger. These have a long tradition in Chile, having been used by protestors of both the left and right. organised by the neighbours in a social housing estate at the corner of my street. And in the following days I went to demonstrations both locally and in the centre of Santiago.

The demands started with the 30 peso hike in metro fares. That might not seem like much, but it came on top of multiple previous fare rises and other abuses we’d constantly had to put up with. Then came the slogan ‘It’s not the 30 pesos, it’s the 30 years’, referring to the steady erosion of living standards which millions had had to put up with since the end of the dictatorship. Very swiftly the demands moved on from the metro fare rises to the numerous demands that had emerged in earlier demonstrations: free, good quality education; free healthcare for all; decent wages; an end to the AFP pension system which makes profits from the money paid into pension funds; abolition of the TAG system of tolls on motorways; an end to machista violence; free basic services like electricity and water; protection for the environment and fauna.

During that time, Chile was transformed. As you walked down the street you would hear cars hooting to the characteristic rhythm of the demonstrations, ‘Peep, peep, pe-pe-peep’; people would call out greetings to each other when they saw their protest slogans. On the marches, too, everyone looked out for the person next to them: offering water with bicarbonate of soda to soothe the irritation from tear gas; passing around masks to protect against the gas; helping others get away to safer places when Carabineros started to get violent. This was a wonderful moment, and it’s what we still see today, despite the lockdowns, when we meet on the street.

Nevertheless, there was still a lot of fear. The government had decreed a curfew and the military had gone out, rifles at the ready, just like during the dictatorship. Numerous videos started circulating on social media, showing the repression, people being seriously injured, soldiers, Carabineros and detectives shooting at people. There are some videos I’ll never forget: a woman lying on the ground, bleeding, after they shot her in the groin; a young man, bleeding but unconscious, being dragged into a barracks by soldiers; a squad of more than 50 soldiers running with their guns, beating and shooting whoever they came across, like they were at war; a police car moving at high speed and then veering onto the pavement, running down pedestrians in its path; a Mapuche 6)The Mapuche are the largest indigenous group in Chile, concentrated mainly in the south, but with many living in cities throughout the country, often subjected to racism and discrimination. man being carried out on a stretcher by paramedics after the military had opened fire inside his home; a man falling to the ground, motionless, after being shot in the head by a teargas bomb; a teenage boy being run over by two police cars, broadcast live on TV. And on top of all that, the warnings from the doctors and health unions about a recurrent phenomenon: an alarming increase in eye injuries, reaching the levels found in countries at war, like Israel.

It never occurred to me that this could happen to me, too. I’m a very cautious person, and I only went to peaceful demonstrations, leaving as soon as I saw any violence. Now I think how naive I must have been to think that just because I was cautious, nothing could happen to me. It didn’t matter how many precautions you took: police violence was completely disproportionate and the President had declared war on us in a nationwide broadcast.

Watch out

On October 28, ten days after the uprising began, I was on my way to join a demonstration assembling near the Moneda Palace.7)Right in the centre of Santiago, the Palacio de la Moneda is the traditional seat of government, the 10 Downing Street of Chile. On 11 September 1973 it was largely destroyed by the Chilean Air Force during the military coup, and President Salvador Allende died there that afternoon. Now fully restored, it has immense symbolic significance for all Chileans. I arrived at around 4:50pm. Everything was peaceful. Lots of people were sitting on the ground, some were eating as there was a cart selling mote con huesillo. 8)Mote con huesillo is a traditional Chilean soft drink, sold on the streets from kiosks and carts. It’s made from the juice of dried peaches (huesillo), with soft, cooked wheat grains (mote). It’s refreshing and filling. Others were carrying placards or chanting or waiting for others to join. That’s what I was doing. I took out my phone to message the friend I was meeting. In a matter of seconds a tear-gas truck rapidly drove up through Paseo Bulnes, a pedestrianised area opposite the Moneda. We had to get out of the way quickly to avoid being run over. Straight away, Carabineros appeared on foot with tear-gas guns, shooting grenades into the air. I was standing on a planter, to see what was going on. When I started to run, a young man held out his hand to help me down, and another threw water with bicarb on me to soften the effects of the tear gas. I swerved into a smaller side street, thinking that they would only deploy across the Paseo, which is a large space. I managed to run about one block and then turned round to my left to see if the police were still close behind us. I remember that in front of me, a woman was running with a child of about six years old, probably nothing to do with the demonstration. At the moment I turned, I heard a shot and immediately felt a violent blow, so violent I can’t find words to describe it. I didn’t feel anything more. My face was immediately paralysed. I couldn’t feel my eye, my cheek or my lip – the whole of the right half of my face was paralysed. Instinctively I raised my hand to my eye to press it, and for a microsecond I thought: ‘No, this is a dream.’ A second later I tried to start walking, but I was dizzy. Fortunately a young man saw me, a paramedic. He helped me into a restaurant where they gave me first aid and then found a car to take me to hospital.

Afterwards, I had three operations to try to repair the damage, but they couldn’t save my eye. They had to remove it. Then came weeks of resting, when I couldn’t get out of bed; months when I lost my independence, suffered post-traumatic stress and required psychiatric treatment.

Hunger for justice

The strength I have today to carry on with my life comes from a hunger for justice. I quickly began to make my case public, giving all the interviews I was asked to do. I began to join human rights organisations and take part in the Coordinating Committee of Victims of Eye Injuries, where we are still working daily to demand justice for everything they stole from us.

As part of this struggle, the opportunity arose to push forward a process for obtaining a new constitution. But it didn’t take the form we expected. Yet again, the political parties and the government entered into agreement behind our backs: in the so-called Acuerdo por la Paz (Agreement for Peace). This was, in effect, a life raft for Sebastián Piñera9) Sebastián Piñera was president of Chile from 2010-2014 and now again from 2018 to the present. One of the richest men in Chile, he belongs to the Renovación Nacional party. and his government which was falling apart and trying to go on providing total impunity for the human rights violations which had occurred: the injuries, the torture, the abuse, the rapes, the mutilations, the arrests and the killings.

However, it became vital that the population took over this process, rather than leaving it in the hands of ‘los mismos de siempre’ (‘the old gang’), i.e. the same politicians as always, the privileged political class, the businessmen and the people who have taken over this country to run it for their own benefit. Now new, independent forces came forward, pressing for the Plebiscito del Apruebo (the Plebiscite for Approval)10)The Plebiscito del Apruebo was a key demand of those pressing for Chile to have a new constitution, to replace the one drawn up by the Pinochet dictatorship and adopted in 1981. This had been modified to some extent after the end of the dictatorship, but its core values and many of its provisions remained in place. After delays caused by the Covid pandemic, the Plebiscite was finally held on 25 October 2020 and 78% of the votes cast were for ‘Apruebo’ – approving the principle of drawing up a new constitution. A second question on the ballot drew an 80 per cent vote to establish a fully elected Constitutional Convention (rather than one in which the existing Congress would have half the seats). This was a resounding victory for all who had been pressing and demonstrating for change.. Different social organisations got involved, non-political public figures, social movements and communities, all calling on people to vote. It was a lovely campaign that vividly showed the unity operating in the streets. Flags and banners were everywhere, but not Chilean flags; flags of the Mapuche people; flags with the symbol of the negro matapacos 11)The ‘Black Cop-Killer’ is a black dog that first became famous when it appeared in the 2011 demonstrations and was credited with helping to protect the marchers., a black dog which became famous after it appeared at so many of the protests.

During the estallido social and the subsequent period of preparations for the Plebiscito del Apruebo, many local organisations, assemblies and cabildos 12)A cabildo is the meeting of a council made up of local people, leaders or householders. Among the Mapuche and indigenous groups, the cabildo was the traditional decision-making body. were set up. Collective forms of organisation quickly began to proliferate. While demonstrations were being called, in parallel, calls went out to join in street assemblies where, among neighbours and local people, we could discuss the new constitution, the implications of the process and the changes that were needed.

Everyone took part – lawyers and professionals were invited to give talks to the wider public, to pass on their knowledge; neighbours and locals came together to discuss their needs; organisation leaders launched activities to publicise and educate. It wasn’t just the political parties and social organisations, everyone wanted to take part. I can remember having planned discussion groups with my own circle of friends and lots of others did this too.

Finally, the Apruebo (‘I approve’) won, with 78.28 per cent in support of drawing up a new constitution. After these results, we quickly started to plan the process of establishing a constitutional convention and people began to discuss candidates. A lot of people encouraged me to put myself forward. At first I didn’t think it was possible, but when they offered me slots on several slates to stand, I began to think it was something I could do. I think in Chile we are too used to thinking that the people who hold political office should be wealthy people, relatives of politicians or members of the elite, and that’s why I didn’t think it was for me. But then I realised that that’s exactly the problem: we’ve allowed useless people to become politicians, just because they’ve made us believe they’re equipped to do the job, when in reality they’ve only legislated and governed in their own interests.

Constituent Candidate

I agreed to run as an independent on the list of the Convergencia Social 13)Convergencia Social describe themselves thus: ‘We are the Convergence of four movements from the Frente Amplio who have decided to join forces to create a new political party: feminist, socialist, emancipatory. We hold out our hands to social movements in every area and nation of Chile to help us build a decent society and a new relationship with all our peoples and our common wealth.’ party, because it is a relatively new party which hasn’t perpetuated the neoliberal model since the end of the dictatorship as the parties of the former Concertación 14)The Concertación was a coalition of various centre and left parties founded in 1988 and which won elections and remained in power from 1990-2010. Initially successful in managing a peaceful transition from dictatorship, it failed to dismantle key provisions of the 1980 constitution and largely preserved the neoliberal economy instituted by Pinochet’s ‘Chicago Boy’ advisers, disciples of Milton Friedman. have done.

My team was made up of family members, friends and people who believed in the project I was putting forward. We wanted to ‘do politics’ in a new way, without making promises that would never be fulfilled just to win votes, and we wanted the proposals that were put forward to be agreed between the communities and local organisations.

We drew up a programme which had seven basic points: feminism, human rights, participatory democracy, workers’ rights, protection of animals and the environment, and ending the estado subsidiario 15)Estado subsidiario is a concept embodied in the Chilean constitution of 1980. The basic principle is that the state should intervene only in activities which private enterprise and the market are unable to carry out., to be replaced by a guarantee of rights and the establishment of a decentralised and plurinational 16)Plurinational refers to Chile’s Mapuche and other peoples and the concept of a state made up of many nations. state.

The campaign on the streets was really rewarding. In general I got a really good reception because my candidacy represented the same interests as those which came to the fore in the social rebellion, and this was reflected in the outcome of the ballot. I got the fourth largest number of votes in my district and the highest number of those on my list. However, I was excluded because of the gender parity requirement.

For the first time in history, we succeeded in stipulating that a constitution should be drawn up by equal numbers of men and women. Women have always been excluded from politics and that is why we fought to enshrine parity both in the selection of candidates and in the election results. In my district we were to elect four constituyentes 17)Constituyentes are members of the constitutional convention.: two women and two men. The results showed three women and one man in the top four places, and as I was the woman in third place, I had to give up my win to the man on my list with the highest number of votes. I had obtained 13,800 votes, a lot for our district, given our very scarce resources, but in the end Marcos Barraza was elected with 11,200 votes. Barraza is a member of the Communist Party and a former minister in the government of Michelle Bachelet.

Overall, the parity principle yielded excellent results. Without it, it would have been impossible to ensure that the Convention was made up half of women. Parity enabled credible women candidates to be selected for parties and lists, and encouraged the electorate to back the female vote. Nevertheless, it excluded 13 women, who were replaced by men.

Perhaps parity is not the best principle, since the final objective is not to secure an equal number of men and women, but to include women, as historically we have been relegated from politics. It shouldn’t operate as a mechanism to exclude women. Perhaps a better option would have been to set minimum quotas for women’s participation – for example that at least 40 per cent of those elected should be women, but that if more women than that were elected, it would not be necessary to swap them for men.

The red thread

A year and eight months have gone by since the beginning of the revolt and Chile is not the same country. Plaza Dignidad (which is what we now call the Plaza Baquedano) hasn’t a blade of grass left, after being trampled by so many demonstrators; buildings and walls are covered with graffiti referring to the estallido: ‘Piñera out’, ‘ACAB’18)‘ACAB’, an acronym for the phrase ‘All Cops Are Bastards’, is used as a political slogan of anti-police and anti-establishment sentiment. It is often seen on political banners, in tattoos and written on public walls by graffiti artists and protesters. Although the phrase originated in the UK, it has been adopted worldwide by those denouncing police brutality. It was widely used as a slogan in Chile’s estallido social in response to brutal state violence., ‘until dignity becomes the norm’ and others. Many who used to back the right no longer do so, because they have seen the damage that they’ve done to people by unleashing police repression. Perhaps aesthetically our country is uglier, but we can see that underneath are ideals and beautiful slogans that call for an end to injustice and inequality.

I am certain that what is happening in Chile will be repeated in other countries in Latin America and that in fact, this is already happening. They say that across Latin America there is a red thread which joins us together, so when one country is suffering, others feel it too. The history of colonisation and violence has affected us all equally and now is the time to put an end to it, because until today we’ve witnessed how the same themes are repeated – the powerful seek to appropriate for themselves the resources that belong to all of us on this earth. I hope this can be the start of Latin America’s liberation.

They say that across Latin America there is a red thread which joins us together, so when one country is suffering, others feel it too. […] I hope this can be the start of Latin America’s liberation.

***

All images below are property of the author, unless otherwise stated. To read more of LAB’s Chile coverage head to lab.org.uk/chile

References

| ↑1 | A toma in Chile is a squat – the seizure and occupation of land. Many of the poorer areas of Santiago began as squats, dating from the 1960s-70s, where pobladores would move into a vacant piece of land, often at night, plant the Chilean flag and erect callampas, shacks of wood and cardboard. Evictions were often violent. Those that managed to survive and stay put would gradually transform their población, erect permanent buildings, get connections to water, electricity and drainage, and obtain legal recognition from the authorities – at least until the military dictatorship put a stop to it. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Educación municipal means ‘state schools’, dependent on the municipio or council, in the way schools in the UK are (or were) run by the local education authority. |

| ↑3 | The ‘Penguin Revolution’ or ‘The March of the Penguins’ was so-called because of the appearance of thousands of school students marching in their school uniforms. |

| ↑4 | Estallido social (social outbreak or uprising) is the term now widely used in Chile to describe the steadily growing wave of protests, marches, demonstrations and direct action which perhaps began with the secondary school students’ ‘Penguin Revolution’ around 2006 and has continued and grown ever since, culminating in the referendum that launched the present process to draft a new constitution. |

| ↑5 | A caceroleo (pan-bashing) is when people go onto balconies or into the streets, bashing pots and pans with spoons to make a cacophony of protest, with empty pots symbolising hunger. These have a long tradition in Chile, having been used by protestors of both the left and right. |

| ↑6 | The Mapuche are the largest indigenous group in Chile, concentrated mainly in the south, but with many living in cities throughout the country, often subjected to racism and discrimination. |

| ↑7 | Right in the centre of Santiago, the Palacio de la Moneda is the traditional seat of government, the 10 Downing Street of Chile. On 11 September 1973 it was largely destroyed by the Chilean Air Force during the military coup, and President Salvador Allende died there that afternoon. Now fully restored, it has immense symbolic significance for all Chileans. |

| ↑8 | Mote con huesillo is a traditional Chilean soft drink, sold on the streets from kiosks and carts. It’s made from the juice of dried peaches (huesillo), with soft, cooked wheat grains (mote). It’s refreshing and filling. |

| ↑9 | Sebastián Piñera was president of Chile from 2010-2014 and now again from 2018 to the present. One of the richest men in Chile, he belongs to the Renovación Nacional party. |

| ↑10 | The Plebiscito del Apruebo was a key demand of those pressing for Chile to have a new constitution, to replace the one drawn up by the Pinochet dictatorship and adopted in 1981. This had been modified to some extent after the end of the dictatorship, but its core values and many of its provisions remained in place. After delays caused by the Covid pandemic, the Plebiscite was finally held on 25 October 2020 and 78% of the votes cast were for ‘Apruebo’ – approving the principle of drawing up a new constitution. A second question on the ballot drew an 80 per cent vote to establish a fully elected Constitutional Convention (rather than one in which the existing Congress would have half the seats). This was a resounding victory for all who had been pressing and demonstrating for change. |

| ↑11 | The ‘Black Cop-Killer’ is a black dog that first became famous when it appeared in the 2011 demonstrations and was credited with helping to protect the marchers. |

| ↑12 | A cabildo is the meeting of a council made up of local people, leaders or householders. Among the Mapuche and indigenous groups, the cabildo was the traditional decision-making body. |

| ↑13 | Convergencia Social describe themselves thus: ‘We are the Convergence of four movements from the Frente Amplio who have decided to join forces to create a new political party: feminist, socialist, emancipatory. We hold out our hands to social movements in every area and nation of Chile to help us build a decent society and a new relationship with all our peoples and our common wealth.’ |

| ↑14 | The Concertación was a coalition of various centre and left parties founded in 1988 and which won elections and remained in power from 1990-2010. Initially successful in managing a peaceful transition from dictatorship, it failed to dismantle key provisions of the 1980 constitution and largely preserved the neoliberal economy instituted by Pinochet’s ‘Chicago Boy’ advisers, disciples of Milton Friedman. |

| ↑15 | Estado subsidiario is a concept embodied in the Chilean constitution of 1980. The basic principle is that the state should intervene only in activities which private enterprise and the market are unable to carry out. |

| ↑16 | Plurinational refers to Chile’s Mapuche and other peoples and the concept of a state made up of many nations. |

| ↑17 | Constituyentes are members of the constitutional convention. |

| ↑18 | ‘ACAB’, an acronym for the phrase ‘All Cops Are Bastards’, is used as a political slogan of anti-police and anti-establishment sentiment. It is often seen on political banners, in tattoos and written on public walls by graffiti artists and protesters. Although the phrase originated in the UK, it has been adopted worldwide by those denouncing police brutality. It was widely used as a slogan in Chile’s estallido social in response to brutal state violence. |