Translated for LAB by Mike Gatehouse. Click to see original in Spanish.

Main image: El Bajío, Sonora. Photo: Giuliano Salvatore, septiembre 2023

It’s so hard for Abigail to talk about the imprisonment of her dad, Bartolo Pacheco. He is one of the five members of the Ejido El Bajío arrested on 13 April 2016 for defending their land against a gold mine belonging to a company owned by the powerful Mexican Peñoles Group, controlled by the Baillères family.

‘It doesn’t seem fair to me, but at the same time it makes you more determined than ever. Because you can’t just do nothing when the law treats you like a criminal when you aren’t one. Because they were innocent, because they looked after their land, because they defended what was theirs, they took them away like criminals. No! I couldn’t believe it and I never imagined being in a situation like this,’ says Abigail, amidst her tears.

When her father was arrested, Abigail was forced to make a difficult decision to help her family to survive economically. She would look for a job with the same company, but in their La Herradura mine, an opencast gold mine which borders on their ejido and in places has invaded their land. She would do this and have to confront the same discrimination, exploitation of labour and health risks.

‘My daughter was getting bigger, already 18 months old, so what could I do? My brothers were students, so I decided to look for work to help out a bit, to help my family, my mum and dad and my brothers, as best I could. At that time my husband was working, so he helped me with the application. But he thought they wouldn’t accept us, children of ejido members, you know.’

Through the Red Mexicana de Afectadas y Afectados por la Minería (REMA), we took part in a conference on Community, Mining and Journalism this September, held on the land of Ejido El Bajío, located in the Great Altar Desert, on the Gulf of California, between Puerto Peñasco and Caborca, Sonora. This desert, unique in North America for its dunes, its spectacular colours and the clearness of its dawns and sunsets, deserves our attention for the beauty and diversity of cactus varieties and the timid animals which inhabit this land of savage heat and important diversity. This beautiful and imposing desert is home both to species in danger of extinction, such as the Sonora antelope, and to landscapes full of life and persistence.

Organized by the ejido and the Bajío Sahuaro Foundation, this conference gave us the opportunity to recognize the important victories and tough sacrifices made by the men and women of the ejido, who are carrying on the struggle to exercise their collective rights and defend their lands.

The illegal Soledad-Dipolos mine and the abuse of power by the mining company, Fresnillo PLC

A huge deployment of 33 police patrolmen, accompanied by the private security guards of the Penmont mining company, a subsidiary of Fresnillo PLC, arrived in the ejido that day in April 2016 when they arrested Bartolo and four other comrades. Fresnillo is listed on the London Stock Exchange and claims to be the largest exporter of silver in the world. The police were acting on a complaint lodged by Rafael Pavlovich, uncle of the then governor of Sonora, who was also interested in the ejido’s land.

However, it was the Penmont company which was operating illegally.

Since the end of the 1900s, the company had been operating in the ejido under agreements reached with a small group of ejido members. The agreements of 2002 and 2005 were never ratified by the ejido assembly, the official governing body of the ejido, and had never been signed by the ejido council. Instead they were signed by a notary and the representatives of the mining company. In 2010 the company put the Soledad-Dipolos gold mine into commercial production.

By that time tensions were rising between the company and the majority of ejido members. They, making full use of their farming rights, secured a victory over the company – something highly unusual in conflicts with the large mining companies. In December 2014, the Magistrate of the United Agrarian Tribunal for District 28, issued 67 rulings in favour of the ejido. These ordered the company to hand back and reinstate the lands of the ejido, to compensate the Ejido for the damage caused, and in an unprecedented judgement, to return the gold which had been illegally extracted from the ejido’s territory.

However, faced with this historic judgement, impunity has prevailed: the Magistrate was not recognised by the Senate and the judgements have not been enforced.

Since then, to protect their extensive territory of 19,038 hectares (47,000 acres), a group of ejido members has maintained a camp in an area next to the mine. They remain there to oversee the implementation of the rulings and to look after their land, which the tribunal is supposed to do, but is not doing. Those who stay on in the camp have had a lot of support from their own families and the other ejido members, many of whom have had to move away because of the difficult conditions in the ejido, especially the lack of water.

Thanks to the struggle by this ejido and their camp, the mine has been unable to operate for most of the last nine years. However, since the criminal case was brought, violence broke out immediately, at considerable cost to the lives of everyone in the ejido.

The violence that followed after their victory

Margarita López clearly remembers 13 April 2016, when more than 100 police arrived at the camp, together with the company’s private security guards, to arrest five comrades from the ejido, among them her husband Erasmo Santiago. At that time she was not spending the night in the camp, but at the main settlement in the ejido, called El Sahuaro, because her children were still small and needed to get to school.

‘We heard about it after the police arrived. We only just got there as the patrol was taking them away.’

After their lawyer brought pressure to find out where the men had been taken to, Margarita and other ejido women travelled every eight days to see prisoners in the ‘Centre for Social Rehabilitation’ (CERESO) in Caborca. They had to undergo invasive searches before being allowed in. All the food and other things they brought for their partners was inspected and deliberately spoiled during the violent searches.

Erasmo was to remain in prison for one year and eight months, the other comrades for eight months.

‘The joke is that when they grabbed them, they wanted a leader they could screw and put in his place. But when they took Erasmo, they picked the one who spoke out, defied them and told them what they could do with their actions. So, what did they do with him? They just piled more false charges on him so they could keep him inside.’

For the rest of the six year term of Governor Claudia Pavlovich (now Mexican Consul in Barcelona), the wave of violence against the ejido continued apace.

In February 2018, ejido member Raúl Ibarra was murdered, and Noemí Elizabeth López Gutiérrez was disappeared. They were a couple. Margarita tells us that they were the two who always fought harder than all the others.

‘Raúl Ibarra was the one who spoke up most and said he would not leave, and that if some authorities turned up, they could go to the devil. “This is my land,” he said, “And no one is taking me away from here.” He spoke out really strongly, and his wife was the same,’ says Margarita.

Raúl managed to avoid arrest in 2016. He wasn’t in the camp that day and the warning reached him in time. Despite that, Noemí went with the other women when they protested.

‘Noemí Elizabeth was always with us. When we went to visit [the prisoners], she came along to raise the morale of the detainees, telling them not to worry, that it would all turn out well.’

When she came out on our side, probably that counted against her too, because she was the one to speak up. And when she got annoyed she would go in and grab the phone and record what the police were saying inside, she didn’t hold back.

Another leader, José de Jesús Robledo Cruz, who was president of the Ejido Council when the 67 rulings were handed down, fled to the US after being repeatedly threatened. When he returned to Mexico in April 2021, he was murdered alongside María de Jesús Gómez Vega, his wife.

‘As for Chuy Robledo, it was open season against him, because he represented the Council at that time … he was constantly being threatened. In the end I think he dropped his guard and they seized him and his wife. You had to look at his body, because when it was found it was really terrible. They had used a knife to fix a piece of cardboard on his stomach, with the names of all the men of the ejido on it.’

The ejido found out about the murder of the couple and the threat against the other 13 ejido members on the news, and this made them really worried and afraid again.

Reflecting on theses terrible losses, Margarita says, ‘We can’t do anything. They are at rest. But their struggle will not be in vain. They made a great sacrifice and they suffered terribly, but their struggle was worthwhile and we are going to carry it on to make sure that it was worth their while, what they did, and we will carry on until we win.’

Rapacious extractive mining and its damage to health

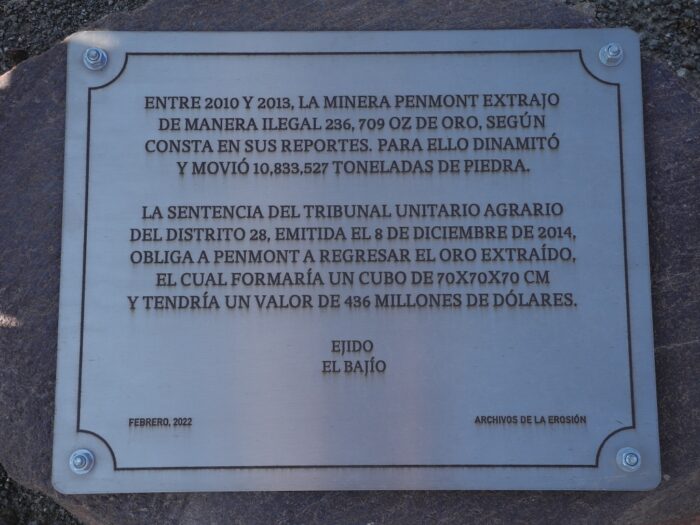

In just three years of operations, the Fresnillo company extracted 236,709 ounces of gold from the Soledad-Dipolos mine, enough to fill a 70 centimetre cube. Yet this left an enormous hole in the ground and more than 3,000 hectares of land destroyed with millions of tons of rock and toxic residues of the ore left behind, which will remain for ever in the territory of El Bajío. The mounds of tailings can be seen like vast levelled and extended platforms, contrasting with the silhouettes of the Western Sierra Madre.

The artist Miguel Fernández de Castro demonstrates the dramatic difference between the tiny quantity of metal extracted and the sheer scale of the destruction wrought by the open-cast mine: he created an installation with a cube of compacted earth and on it a plaque with texts by Natalia Mendoza. After being exhibited in New York, it can now be found inside the workings of the Soledad-Dipolos mine.

Returning this gold to the communities is perfectly possible for this Mexican transnational company. The gold Fresnillo owes to El Bajío is equivalent to 37 per cent of the gold which the company extracted from the seven mines it as operating in Mexico in 2022 alone, or 68 per cent of the gold extracted just form the La Herradura mine that same year.

For some years Margarita and her daughters have spent more time in the camp, alongside Erasmo. But it’s not easy.

Yet even if the company returns the gold, this part of the territory of El Bajío will never get back to its former state.

‘For food we get contributions from the ejido members living away from here, which is a big help. But I’ve got grown-up children with their own families,’ says Margarita. Her sons work outside the ejido and send back all they can afford as their contribution to the struggle.

There’s no water for our crops, either, and even when the mine isn’t in operation, everyone is constantly exposed to the contaminated dust from the leaching pans left by the mine. The exposure to heavy metals such as lead has serious effects on the nervous system. In other communities affected by mining in Mexico, damage to health caused by mining has been observed particularly among pregnant women living near open-cast gold mines, as at Carrizalillo, Guerrero, where for years there has been a marked increase in birth defects, miscarriages and premature births.

Here Abigail, stayed working at the Fresnillo company’s La Herradura mine, to help her family after her father’s arrest. She was working in the mine laboratory and not long after starting there she became pregnant.

‘In the area where I was working, I stayed at the same post, five days a week for two months. I was breathing in all the steam until the supervisors themselves said, “Hey, the extractor isn’t working.” It gives you a taste in your mouth like pumpkin caramel [a traditional dessert in Sonora] – once you taste it you can’t get rid of it, even if you drink water. The supervisors know perfectly well that it’s the lead, and just the smell, the taste are enough for them to say “Check the extractor”.’

‘We had special clothing, but the lead just works its way through everything. Even though they claim that they’ve got all the controls in place, you’re still in contact with it,’ says Abigail.

Her second daughter was born with spina bifida and other health problems. Now Abigail is pregnant again. Struggling to ensure that her child can learn to walk and play like the other little girls is a tremendous challenge, especially now, as she was given the sack a few months ago and is fighting to get the back-pay she is owed.

‘I only hope they pay me what I’m owed, as well as for all the damage they have done to us.’

Long live the Great Desert of Altar and its people

The fight put up by the El Bajío ejido continues, their eyes firmly fixed on securing a better future for their families and for everyone who lives in their territory. They are fighting, not just for the implementation of the 67 rulings of the Agrarian Tribunal, but for justice, given the violence they have suffered, and to restore the habitat in their lands with its rich and important flora and fauna.

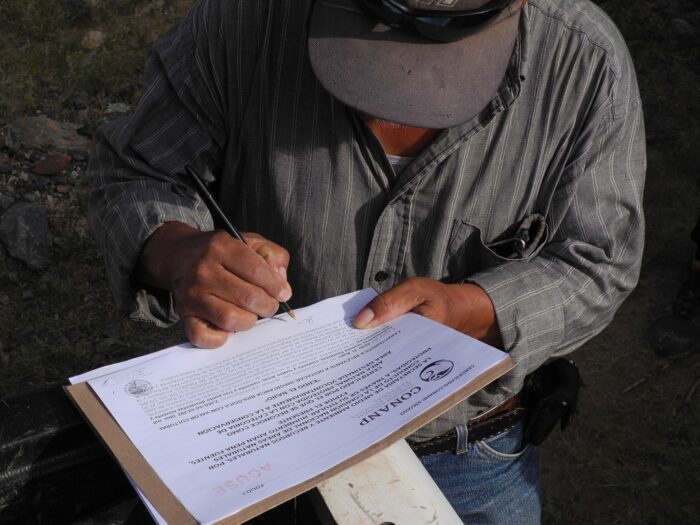

While we were visiting their encampment, Abigail’s father signed an certificate to convert the 2,460 hectares of the ejido into a Voluntary Conservation Area. Abigail hopes that the project which will emerge from this and from their struggle can improve the situation for the whole ejido, as well as for all the flora and fauna of the beautiful Altar desert.

Margarita says she is happy at the rulings they won, but that she is determined to carry on the struggle, so that all the sacrifices they have made are worthwhile and that it all means something to their successors in the future. ‘We just want to carry on,’ she says, ‘to take better care of the animals and the plants, so that they don’t keep getting destroyed.’

For herself, she hope’s she’ll get a chance to rest a bit, to spend more time with her family, and to sow her crops.

‘We love growing things,’ she says, smiling.

Original version in Spanish:

Hacer valer los sacrificios de la lucha por la vida en el Gran Desierto de Altar de Sonora

Por: Red Mexicana de Afectadas y Afectados por la Minería (REMA)

Es muy difícil para Abigail hablar del encarcelamiento de su papá, Bartolo Pacheco. Él es uno de los cinco ejidatarios del ejido El Bajío detenidos el 13 de abril de 2016 por defender su territorio de una mina de oro que pertenece a una empresa del poderoso grupo mexicano Peñoles, controlado por la familia Baillères.

“No se me hace justo y a la vez te da mucho coraje porque no puedes hacer nada, viendo como la misma ley te trata de ver como una persona mala, cuando no lo eres. Ellos por ser inocentes, por cuidar sus tierras, por defender lo de ellos, los llevan como si fueran criminales. Pues, no. No lo podía creer y nunca me imaginé estar en esta situación,” nos dice Abigail entre lágrimas.

Frente a la detención de su padre, Abigail tuvo que tomar una difícil decisión para ayudar la economía familiar. Buscaría trabajo en la misma empresa, pero en la mina La Herradura, una mina de oro a cielo abierto que colinda con su ejido y que inclusive ha invadido una parte de sus tierras. Haría esto enfrentando la discriminación, explotación laboral y riesgos a la salud.

“Tenía mi niña grandecita un año y seis meses, y dije, ¿qué vamos a hacer? Mis hermanos [estaban] estudiando y decidí buscar trabajar para ayudar un poquito a mi familia, mi mamá, mi papá, lo que sea, mis hermanos. Y la opción fue la mina. En este tiempo, mi esposo estaba trabajando y fue el que me ayudó con la solicitud, y sí. Pero, pensaba que no nos iba a aceptar porque, por ser hijos de ejidatarios, ¿no?”

Por parte de la Red Mexicana de Afectadas y Afectados por la Minería (REMA), participamos en el encuentro Comunidad-Minería-Periodismo en septiembre de este año dentro del territorio del ejido El Bajío, ubicado en el Gran Desierto de Altar frente el Golfo de California, entre Puerto Peñasco y Caborca, Sonora. En este desierto, único en su tipo en toda América del Norte por sus dunas, los espectaculares colores y la frescura de sus amaneceres y atardeceres invitan a reflexionar sobre la belleza de la diversidad de cactáceas y especies de fauna tímidas que habitan estas tierras de calor hostil, pero de una diversidad importante. Este hermoso e imponente desierto resguarda especies en peligro de extinción, como el berrendo sonorense, y paisajes llenos de vida y resistencia.

Organizado por el ejido y la Fundación Bajío Sahuaro, este encuentro nos dio la oportunidad de conocer de cerca las importantes victorias y los difíciles sacrificios que han hecho las mujeres y hombres del ejido, quienes siguen en la lucha para hacer valer sus derechos colectivos y para defender sus tierras.

La mina ilegal Soledad-Dipolos y los abusos de poder de la empresa minera Fresnillo PLC

Un enorme despliegue de 33 patrullas acompañado por la seguridad privada de la empresa minera Penmont, subsidiaria de la Fresnillo PLC, se presentaron en el Ejido aquel día de abril 2016 que detuvieron a Bartolo y cuatro compañeros más. Fresnillo cotiza en la bolsa de valores de Londres y presume ser la principal explotadora de plata en el mundo. Las policías respondieron a una denuncia interpuesta por Rafael Pavlovich Durazo, el tío de la entonces gobernadora de Sonora, quien también había mostrado interés en las tierras del ejido.

Sin embargo, fue la empresa Penmont la que estaba operando en la ilegalidad.

Desde fines de los años noventa, la empresa operó en el ejido mediante convenios acordados con un pequeño grupo de ejidatarios. Los convenios de los años 2002 y 2005 jamás fueron ratificados por la Asamblea Ejidal, la máxima autoridad del ejido, y tampoco cuentan con la firma del Comisariado Ejidal, sino de un notario y de los representantes de la empresa minera. En 2010, la empresa puso en operación comercial la mina de oro Soledad-Dipolos. Pero para entonces ya habían crecido las tensiones entre la empresa y la mayoría de los y las ejidatarios quienes, en pleno ejercicio de sus derechos agrarios, lograron una victoria poco común entre las luchas contra las grandes empresas mineras. En diciembre de 2014, el Magistrado del Tribunal Unitario Agrario de Distrito Veintiocho dictó 67 sentencias a favor del ejido. Las sentencias ordenaron a la empresa entregar y reparar las tierras del ejido, indemnizar al Ejido por los daños generados y, algo inédito, devolver el oro que se había extraído de forma irregular de su territorio. Sin embargo, frente a esa sentencia histórica, la impunidad se ha antepuesto: el Magistrado no fue ratificado por el Senado y las sentencias aún no han sido ejecutadas.

Desde ese entonces, para proteger su amplio territorio de 19 mil 38 hectáreas, un grupo de ejidatarios ha mantenido un campamento en un área cercana a donde se encuentra la mina. Están ahí para vigilar la implementación de las sentencias y cuidar su terreno, haciendo lo que el tribunal debería hacer, pero que no ha hecho. Quienes resisten en el campamento han contado con mucho apoyo de sus familias y de los demás ejidatarios, muchos de los cuales han tenido que desplazarse a otros lados, dadas las difíciles condiciones que se presentan en el ejido, especialmente la falta de agua.

Gracias a la lucha de este ejido y al campamento que sostienen, durante la mayor parte de los últimos nueve años, la mina no ha operado. Sin embargo, desde esta sentencia la criminalización y la violencia escaló inmediatamente, con grandes costos para la vida de todo el ejido.

La violencia que siguió a la victoria

Margarita López recuerda claramente el día 13 de abril de 2016, cuando más de cien policías llegaron al campamento junto con la seguridad privada de la empresa para detener a cinco compañeros del ejido, entre ellos su esposo Erasmo Santiago. En este momento, ella no pasaba las noches en el campamento, sino en el centro habitacional del ejido que se llama El Sahuaro, debido a que sus hijos aún eran pequeños y necesitaban ir a la escuela.

“A nosotros nos avisaron ya cuando llegaron la policía… Veníamos entrando cuando la patrulla ya iba saliendo con ellos.”

Después de presionar mediante su abogado para saber a dónde los había llevado, ella y otras compañeras del ejido iban cada ocho días para verlos en la cárcel Centro de Reinserción Social (CERESO), en Caborca. Tuvieron que pasar por revisiones invasivas para poder entrar. Toda la comida y otras cosas que llevaban para sus compañeros fue inspeccionada y estropeada adrede con tan violenta verificación.

Erasmo se quedaría en la cárcel un año y ocho meses, mientras que los demás compañeros lo harían por ocho meses.

“El chiste es que cuando lo agarraron [ellos] querían un líder para chingarlo y colocarlo en su lugar. Y cuando agarraron a Erasmo, [que] es quien habló más, es quien le andaba más a la madre, a la fregada y todo esto. Entonces, ¿qué hicieron con él? Por eso le pusieron más cargos falsos, para que él se quedaba allí adentro.”

Durante el resto del sexenio de la Gobernadora Claudia Pavlovich, ahora cónsul de México en Barcelona, la violencia se mantuvo muy fuerte en contra del ejido.

En febrero de 2018, el ejidatario Raúl Ibarra fue asesinado, y Noemí Elizabeth López Gutiérrez desaparecida. Eran esposos. Margarita nos dice que ellos eran los que siempre lucharon más que todos.

“Raúl Ibarra era quien más hablaba también que el no se dejaba, si entraba un gobierno, él le mandaba hasta la madre. Decía que aquí es mi tierra y nadie me va a sacar de aquí. Él hablaba duro. Y su señora es igual,” dice Margarita.

Raúl logró evitar ser detenido en 2016. No estuvo en el campamento este día y le llegó el aviso a tiempo. Aún así, Noemí acompañaba a las compañeras.

“Noemí Elizabeth siempre estuvo con nosotras. Cuando [los] íbamos a visitar, ella también iba y daba ánimo a los que estaban adentro, que no se preocupa, que todo iba a salir bien.”

“Ella, cuando fue a pelear con nosotros, a lo mejor para esto fue en contra de ella también, porque ella es la que hablaba más. Y cuando se enojaba, ella entraba y agarraba el teléfono y le grababa a los policías allí adentro y no se detenía.”

Otro líder, José de Jesús Robledo Cruz, quien era el presidente del comisariado ejidal en el momento que salieron las 67 sentencias, huyó a los Estados Unidos por todas las amenazas que enfrentaba. Sin embargo, cuando volvió a México, en abril de 2021, fue asesinado junto con María de Jesús Gómez Vega, su esposa.

“Por parte de Chuy Robledo, pues, fue ensaña en contra de él porque fue el Comisariado en aquellos tiempos. … Todo el tiempo ha tenido amenazas. Y el último, pues, creo que se descuidó y lo agarraron con todo y su señora, pues. Y se mira en el cuerpo, porque cuando lo encontraron estaba bien feo. … Y en su cuerpo, cuando se murió, le puso un cartón con cuchillo en la panza con los nombres de todos los hombres ejidatarios.”

El ejido se enteró del asesinado de la pareja y de la amenaza en contra de los 13 ejidatarios por los noticieros, y esto les generó mucho miedo y preocupación nuevamente.

Reflexionando sobre estas grandes pérdidas, Margarita dice, “No podemos hacer nada, están descansando. Pero su lucha no va a quedar en vano, los que hicieron un sacrificio también les pasó lamentablemente, pero su lucha valía la pena y nosotros vamos a seguir adelante para que valga la pena lo que ellos hicieron y vamos a seguir hasta que ganamos.”

El extractivismo minero rapaz y los daños a la salud

En tan solo tres años de operación, la empresa Fresnillo sacó 236,709 onzas de oro de la mina Soledad-Dipolos, una cantidad que cabe en un cubo de 70 centímetros por 70 centímetros. Sin embargo, dejó un hueco enorme y más de 3 mil hectáreas destruidas con millones de toneladas de roca y residuos tóxicos del mineral procesado, residuos que permanecerán para siempre en el territorio de El Bajío. Los desechos amontonados se muestran en el horizonte como grandes escalones planos y alargados que contrastan con las siluetas accidentadas de la Sierra Madre Occidental.

El artista Miguel Fernández de Castro expone la dramática diferencia entre la pequeña cantidad de mineral extraído y la magnitud de la destrucción generada por la mina de tajo abierto, con la instalación de un cubo de tierra compactada marcada con una placa con textos de Natalia Mendoza. Después de mostrarlo en Nueva York, ahora se encuentra dentro del tajo de la mina Soledad-Dipolos. Regresar este oro a la comunidad es algo que está dentro de las posibilidades de esta empresa mexicana transnacional. El oro que Fresnillo debe a El Bajío es equivalente a 37% del oro que la empresa sacó en sus siete minas en operación en México tan solo en 2022, o el 68% del oro extraído solamente de la mina La Herradura el mismo año.

Sin embargo, si bien la empresa podría regresar el oro, esta parte del territorio de El Bajío jamás regresará a su estado anterior.

Desde hace unos años, Margarita y sus hijas permanecen más tiempo en el campamento, junto con Erasmo. Pero no es fácil.

“Lo que comemos, tenemos un poquito de ayuda de los ejidatarios que [viven fuera y] nos ayuda. Y yo tengo también hijos ya grandes por la propia familia” dice Margarita. Sus hijos trabajan fuera y mandan todo que pueden como parte de su contribución a la lucha.

Tampoco hay agua para poder cultivar y, aún cuando la mina no está en operación, todos ellos están constantemente expuestos al polvo contaminado de los patios de lixiviación que dejó la mina. La exposición a metales pesados como el plomo tiene impactos sobre el sistema nervioso. En otras comunidades afectadas por la minería en México los daños a la salud por la minería se han observado particularmente en las mujeres gestantes que viven cerca de las minas de oro a tajo abierto, tal como en el caso de Carrizalillo, Guerrero, donde desde hace años se ha identificado un fuerte aumento en los nacimientos con deformaciones, así como un incremento en los abortos y partos prematuros. Por su parte, Abigail se quedó trabajando en la mina La Herradura de la empresa Fresnillo desde la detención de su papá para ayudar a su familia. Trabajaba en el laboratorio y, poco después de entrar, se embarazó.

“En el área en donde yo trabajaba, estábamos dos meses, cinco días a la semana en el mismo lugar. Inhalar todo el vapor, hasta los mismos facilitadores te dicen, ¿sabes qué?, el colector no está funcionando. Aquí se sienten el sabor como si fuera dulcecito de cala, es algo que tú sientes y es difícil quitártelo, aunque tomas agua, aunque comes algo, allí lo tienes. Hasta los mismos facilitadores saben que es el plomo y con sólo el olor, el sabor, dicen checan el colector.”

Tuvieron su uniforme y ropa especial designada, pero aún así el plomo traspasaba todo: “aunque dicen que tienen todos los controles, aún estás en contacto” comenta Abigail.

Su segunda hija nació con espina bífida y otros problemas de salud. Hoy Abigail está embarazada de nuevo. Luchar para que su hija pueda caminar y jugar como las demás niñas es un gran reto, especialmente ahora, puesto que fue despedida hace unos meses, y ahora lucha para que la empresa le pague lo que le debe.

“Espero que me paguen lo que me correspondan y todo el daño que nos hayan hecho.”

Que viva el Gran Desierto de Altar y su gente

La lucha del ejido El Bajío sigue con la mirada puesta en la lucha por un futuro mejor para sus familias y todos los seres vivos en su territorio. No solo están luchando por la ejecución de las 67 sentencias del Tribunal Agrario y por justicia por toda la violencia que han sufrido, sino también para restaurar el hábitat con la importante flora y fauna que abarca su territorio.

Mientras visitamos su campamento, el papá de Abigail firmó un certificado que convierte 2,460 hectáreas del ejido en un Área Destinada Voluntariamente a la Conservación. Abigail espera que el proyecto que salga de allí y de su lucha pueda mejorar la situación para todo el ejido, y también para toda la flora y fauna del hermoso desierto de Altar.

Margarita dice estar feliz por las sentencias que ganaron, pero para que realmente valga la pena el sacrificio que han hecho y para que esto tenga sentido para quienes vengan en un futuro, lo que quiere es seguir luchando por su territorio: “Seguir adelante es lo que queremos. Cuidar los animales mejor y las plantas, para que ya no destruye.” En lo personal, también espera poder descansar un rato, poder estar más con su familia y sembrar sus tierras. “Nos gusta mucho el cultivar,” dice, sonriendo.