‘El Perrito’, is a chartered mining engineer with more than 40 years experience of the industry. From Central America he sent us his highly critical view of the Economic, Social and Governance (ESG) frameworks to which the large mining companies claim to adhere. In many cases, he argues, these amount to little more than ‘greenwash’, and on occasion they serve to disguise or deflect attention away from much more sinister malpractice.

Anglo-American Corporation´s 2021 Sustainability Report is a slick, glossy and almost Messianic report. It reminds me of the words of the hymn which promise ‘peace on earth and goodwill to men’. Among other gems it claims that the company is ‘reimagining mining to improve peoples´ lives’, that ‘our ability to build partnerships brings a unique lens to the business of uplifting regional economies’, and that it provides ‘a catalyst for self-supporting regional economic activity’.

The 82-page report, posted on its comprehensive website goes on to give promises and commitments on zero carbon, climate change, the biosphere, culture, human rights, anti-slavery, environmental stewardship, social policy, business conduct and supply chains, in fact on almost every area of human – and biological – endeavour.

The first page of Anglo´s sustainability report shows a smiling and attractive young woman selling locally made ice-creams. Like other corporate reports it makes liberal use of digital tools, predictive graphs and sleek colourful graphics, packing its web pages with pictures of smiling children and women. Corporate-speak peppered with long words and technical terms seems designed to induce warm and comfortable feelings, like a bright log fire and a malt whisky on a chilly night. It is surprising that the company has any time and money left to extract ore.

ESG, or Economic, Social and Governance, is the latest child of corporate capitalism which was born at the beginning of this century and championed, among others, by the World Economic Forum, which claims that ESG drives ‘effective transformation of global corporations’ sustainability efforts’, but fails to explain what is to be transformed. Meanwhile the World Bank promotes ‘sustainability finance’ and ESG through the International Finance Corporation, with the enthusiastic endorsement of global consultants McKinsey and Deloitte.

The company´s relentlessly upbeat approach and its many promises to improve the world is what Greenpeace calls greenwash. According to Investopedia, greenwash is false or misleading information designed to depict a company and its products, as environmentally sound. Greenpeace condemns greenwashing as a distraction, that it declares everything is fine when it is not, and delays and stops the ‘actions we need to move to better systems’.

Mining companies have much to hide. Mining is a dirty business; a despoiler of lives and the natural environment. A good ore deposit can raise enormous profits pulling get-rich-quick investors into the game.

Yet the price can be high for the rest of us. We remember the tragedy of the village of Aberfan in South Wales in 1966 when heavy rain collapsed a spoil heap, overwhelming a school and drowning 116 children and 28 adults in coal slurry. In 2019 a Brazilian tailings dam, operated by iron ore miner Vale at Córrego do Feijão, near Brumadinho, gave way and killed 270 people. The British newspaper the Guardian reports on the town of Baotou in Inner Mongolia, the largest Chinese source of ‘green’ technology from smartphones to electric cars, where there is a huge lake of radioactive and toxic chemicals, ‘as far as the eye can see’, produced by the mining and processing of rare earth elements. From the 1930s to the 1990s the gold process plant at Mina El Limon in Nicaragua, spewed out toxic tailings over a wide area and into natural water courses.

These are a few of the more spectacular and tragic examples. Less visible and less well reported are the contamination of surface and groundwater by mines, process plants, tailings ponds and waste dumps; airborne dust and greenhouse gas emissions; loss of biodiversity – especially if waste is not cleaned up after closure; and health effects, such as mercury poisoning by unregulated gold mines in Latin America and Africa. The smaller or ‘junior’ miners can act as vanguards for the major mining companies, even unwittingly.

Complex codes mask poor compliance

The ICMM, the International Council on Mining and Metals, was founded by the mining industry majors in 2001, and promotes ESG and sustainable practices in mining. Its membership comprises global multinationals such as AngloGoldAshanti, Barrick, BHP, Glencore and Goldfields. ICMM works closely with the World Economic Forum and other global cheer leaders and produces several formidable ESG and sustainability codes of practice tailored to suit their members and fellow traveller global organisations.

ESG codes have become increasingly convoluted and complex (the popular Global Resource Initiative has around 120 clauses many of which contain intricate sub-clauses), and this complexity is encouraged by the large mining companies.

Complying with the multiple GRI, SASB (Sustainability Standards Accounting Board), and ICMM codes of conduct is expensive and time consuming and is beyond the reach of many small mining companies.

It is doubtful whether even the larger companies fully meet the standards; compliance leans heavily on the future tense: ‘It is intended to…’, ‘we plan on…’, ‘we pledge to…’, etc. Actual observance is often limited to a small number of easily met targets.

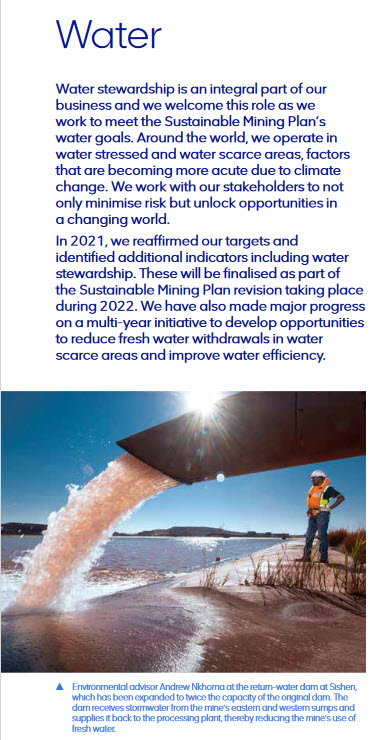

Deep into Anglo´s Sustainability report, I read about the company´s actions in 2021 in relation to water. ‘We continued to install critical monitoring systems’, ‘we piloted a water data collection system’, ‘we rewrote our water commitments’, I read. Busy but ineffective. Why hadn´t they set up monitoring systems before, given that the mine in question had been operating for several years? Clearly the actions taken were at a carefully measured pace, just sufficient to claim to have done something, but without expending too much money or effort.

The reaction of most small miners – in my experience – is to ignore the codes of practice for the most part if not entirely. As a result, Latin America has particularly high levels of conflict around the environmental impacts of mining, especially when the rights of ethnic and indigenous communities are traduced.

A paper by Ann Helwegg (Challenges with resolving mining conflicts in Latin America, Elsevier, 2015) gives some particularly egregious examples, for example: six protestors, including two teenage boys, were shot in 2013 by the Canadian miner Tahoe Resources in Guatemala; and two Mexican environmental rights activists were shot in San José del Progreso by hired gunmen allegedly connected to the Trinidad/Cuzcatlán mine. LAB has reported on many more such violations across the region.

According to the Global Initiative as reported in the Guardian, illegal gold mining by small companies has overtaken cocaine to become one of the largest exports of Peru and Columbia, resulting in taggering scales of human rights abuse and wrecking the environment with toxic chemicals such as mercury.

Other small mining companies, perhaps the more responsible ones, are unable to meet the complex codes of practice championed by the top-tier mining companies, the ICMM, and many regulators. Unable to raise the necessary capital, where institutional investors may regard environmental hazard as a risk, they sell out to larger companies. This benefits the risk-adverse large corporations who get the juniors to locate deposits and do the exploration for them. The shareholders of both sides benefit as the large company increases its stable of reserves and the small company is bought out, often at a handsome profit.

E is for Environmental

The growth of ESG has been matched by the parallel growth of environmentalism, especially in relation to climate change which has become a fashionable concern among western elites. Hence the “E” or Environmental in ESG is largely concerned with climate change prevention, mitigation and above all, managing risk: by reducing carbon emissions, adopting zero carbon measures, renewable energy, electrification to replace diesel power, and planting trees as carbon sinks.

The ‘S’ in ESG is the social element: managing stakeholders and the company´s reputation; control of investors, the public, their own staff, supply chains, labour relations, technology and market trends.

Governance, meanwhile, measures the quality and effectiveness of the company’s board, accounting transparency, ethics, and an emphasis on EDI (equity, diversity and inclusion) throughout the organisation.

Smoke and mirrors

For many companies ESG is a smokescreen, hiding continued abuses or near inaction. Meaningful action is taken only when the company´s reputation is at stake, when their income and profits are threatened, or a government regulator turns nasty.

I have focused on the bad side of mining companies whose CEOs and directors are typically paid eyewatering salaries and share options, and who want to keep the company in stasis and as a cash cow for their benefit, and thus ESG becomes an exercise in smoke and mirrors.

But there are a few responsible mining companies who wish their operations to be sustainable and their associated communities and employees to succeed. They promote ongoing and long term training to provide electricians, plumbers, programmers, welders, drivers, foresters and so on, who will obtain a living once the mine closes; they rehabilitate waste dumps to make them safe and to turn them into valuable agricultural land; and they turn the open pit into wetlands for biodiversity and for tourism. This is the true spirit of sustainability.

Main image: Chuquicamata mine, Chile, the world’s largest open-cast copper mine. Image: Wikimedia

LAB’s new book The Heart of Our Earth – community resistance to mining in Latin America, by Tom Gatehouse (April 2023), discusses this theme extensively, with many more examples of oppressive action by mining companies, their agents and local and state governments against communities who resist the damage and destruction wrought by mining. You can order copies here.