International Delegation stands with mining-affected people to urge administration of President Gustavo Petro to withdraw from corporate courts.

‘Do we have fundamental rights at the international level?’, a Wayúu Indigenous community leader asked during a workshop in La Guajira, Colombia at the end of May.

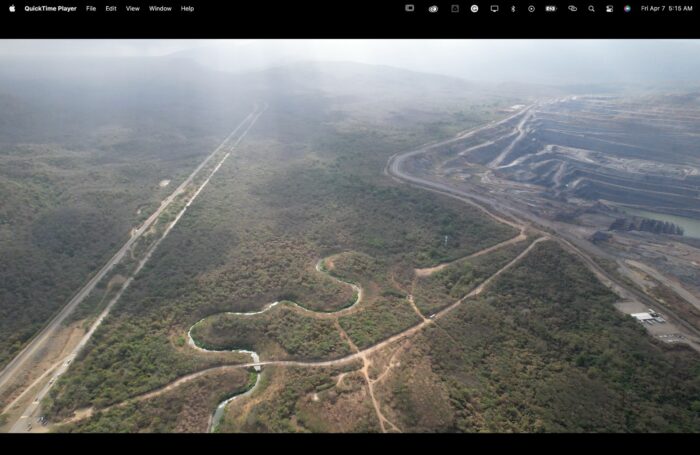

For decades, Wayúu communities have been deeply affected by Latin America’s biggest open-pit coal mine, known as Cerrejón. In 2017, they won an important decision from the Constitutional Court that seeks to protect their rights to water, health and food sovereignty from this mine’s expansion over the last remaining tributary of the Ranchería River, the Bruno stream, on which they depend. Years later, the ruling has yet to be implemented.

Standing in the way are the international investor rights of Swiss mining company Glencore as found in a bilateral investment treaty between Switzerland and Colombia. Glencore has brought an international arbitration claim against Colombia for an unknown sum that is interfering with implementation of the decision, putting pressure on the judiciary and regulatory officials.

During the same workshop, Cindy Forero from the Lawyer’s Collective José Alvear Restrepo (CAJAR) commented that because of the arbitration suit, public officials have been afraid even to talk about the decision and its implementation. ‘On the one hand, there is this arbitration case in process’, she told me. ‘On the other, there is the [state’s] obligation to protect the communities’ fundamental rights. They can’t tell me that they won’t protect their rights out of fear. If that’s the case, then the company is above the state and we’re without a state. These are the implications of this unjust arbitration mechanism.’

the company is above the state and we’re without a state

Cindy Forero, CAJAR

The constitutional court ruling cites as the reason to admit their case the historic discrimination that the Wayúu and other Indigenous peoples have faced in Colombia. Perversely, as Cindy further explained, Glencore argues in its claim that it is the company that the Colombian state treated unfairly as a result of this sentence. Nonetheless, the delegation observed how the company is continuing activities at the La Puente section of the coal mine that should be suspended; and how it has diverted 3.6 kilometers of the Bruno stream into a channel that the Wayúu refer to as a concrete highway, devoid of the life they attribute to the remaining natural streambed.

These injustices were the focus of the workshop and an international delegation to Colombia in May. The International Mission to Stop ISDS (Investor State Dispute Settlement) sought to call attention to the abyss that exists between peoples’ full enjoyment of rights and their curtailment when these are affected by transnational investments, a situation which is compounded by the exclusive recourse that transnational companies have to sue countries when they believe that a state’s decision impacts their investment and future profits.

Fundamentally unjust global investment rules

Together with representatives from a dozen social and environmental justice organizations from eight countries in the Americas and Europe, the delegation in which I participated sought to share experiences from other parts of the world, north and south, where action is being taken against this investor protection system.

We also went to build solidarity and hear first-hand about its implications for frontline communities organizing to defend their territories from mining harms, including those in the departments of La Guajira and Santander.

Colombia has faced an onslaught of 22 investor arbitration suits since 2016 for a total of US $13.2 billion in known claims. This amount is roughly equivalent to the total education budget for the whole of Colombia in 2023. In three of these cases, including Glencore’s, the amount claimed is not even made public.

Betraying the neocolonial nature of this system, companies suing Colombia have relied on free trade agreements and bilateral investment agreements with five countries: Canada, the US, Spain, the UK and Switzerland. Nearly half of these claims have been brought by mining companies and nearly all of these have at their core the struggle of an affected community fighting to protect or seek accountability for harms to their water, land, self-determination or local economy.

Indignation at this extraordinary privilege afforded to transnational corporations has understandably arisen among the Wayúu, organizations like CAJAR, as well as grassroots groups like the Committee for the Defense of Water and Páramo of Santurbán. Prior to the delegation, their concerns were laid out and disseminated through a declaration, Recover Colombia’s sovereignty in defense of water, life and territories, signed by over 280 organizations from 30 countries.

The only way is out

The Committee for the Defense of Water and Páramo of Santurbán has fought for fourteen years to keep industrial gold mining out of a high-altitude wetland unique to the Andes known as páramo.

Páramo and interconnected ecosystems like Andean forest regulate the water supply for tens of millions of people in Colombia, over two million in Santander alone. The Committee’s successful efforts to date have led three Canadian mining companies, Eco Oro, Red Eagle and Galway Gold, to sue Colombia for roughly US$1 billion for protecting the paramo and people’s water.

These cases are ongoing, but an initial ruling against Colombia in the Eco Oro case demonstrates the futility of including language to protect the state’s right to regulate in favor of the environment in agreements such as the Canada Colombia Free Trade Agreement. Rather, as was discussed in meetings with communities, social movement organizations, students, media and government officials, complete withdrawal from the investor protection system is an important step to recover local and national sovereignty to protect people’s health and the environment.

Days after the delegation arrived in Colombia, the Minister of Commerce announced that the country plans to review all of its investment protection agreements. It is unclear, however, how far this might go.

Were Colombia to chart a path to withdraw from ISDS it would not be alone.

As the delegation shared during its meetings, countries as diverse as Ecuador, Bolivia, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, South Africa, New Zealand, Canada, and the US have taken steps to reduce their exposure to international arbitration in recent years. Meanwhile, the European Commission is moving toward a coordinated exit of the European Union from the Energy Charter Treaty, a treaty specific to the energy sector, given the incompatibility of investor-state dispute settlement with measures needed to address the climate crisis.

Weeks after the delegation’s departure from Colombia, in late June, President Gustavo Petro visited La Guajira with members of his cabinet. In a meeting with communities affected by the Cerrejón coal mine, he declared, ‘A sovereign nation is not afraid of international lawsuits when it does what is just.’ This is a welcome promise, raising the community’s hopes and motivation to continue pressing Colombian officials to protect fundamental community rights and return the Bruno stream to its natural course, despite Glencore’s suit.

Nonetheless, as Petro concluded his speech, this will be a difficult task: ‘When one stands up to capital, even Congress becomes afraid to pass laws.’ For this reason, the delegation together with our local partners will also continue urging Colombian officials to plan a withdrawal from this unjust mechanism which transnational corporations use to intimidate and impede.

Jen Moore is an Associate Fellow of the Institute for Policy Studies. She researches, writes and collaborates closely with the struggles of mining-affected communities and allied organizations. From 2010 to 2018 she coordinated the Latin America Program at MiningWatch Canada. She advised LAB on our ‘The Heart of Our Earth’ project which led to our 2023 book of that name.