The Troncal 10 is a road full of huge pot-holes and obstacles that constantly threaten to destroy cars that venture onto it. This ‘trunk road’ leads to Tumeremo, the capital of the Sifontes municipality, in the state of Bolivar in southern Venezuela. The journey is slow and tense, as drivers and passengers are stopped at the frequent military roadblocks and questioned about their reason for traveling to the area, which is feared for its insecurity and violence.

Sifontes is the epicentre of gold mining in Venezuela. Mining has increased considerably since 2016 when the government of Nicolás Maduro launched the ‘Arco Minero’, to permit and promote mining in an area south of the Orinoco River, measuring 111,843.70 square kilometers – larger than Guatemala.

Since then, the scars of deforestation have spread rapidly. According to Global Forest Watch, the state of Bolivar has lost more than 74,600 hectares of primary forest in the last six years.

Now Sifontes has also become the epicentre of the malaria epidemic in Venezuela, which has the highest incidence of the disease in the Americas. The WHO’s latest World Malaria Report reveals that 35 per cent of malaria cases reported in the whole continent originate in Venezuela.

The epidemic increased gradually at first. It progressed from 137,996 cases in 2015 to 242,561 cases in 2016. By 2017 it had exceeded 400,000 cases and reached 467,000 in 2019.

The twin legacy of mining and deforestation

The combination of deforestation and illegal mining is at the core of the reemergence of malaria because it favors both the reproduction of the Anopheles mosquito, which transmits the parasite, and the interaction of the vector with humans.

The increased risk of disease transmission has been aggravated by the gradual dismantling of health infrastructure in recent decades. Epidemiological surveillance is a critical factor in keeping the disease at bay, explains Venezuelan researcher Juan Carlos Gabaldón, from the Institute of Global Health in Barcelona, Spain.

‘When the economic crisis took hold in Venezuela, there was a major explosion of illegal mining activity in the south of the country: a lot of people from other states in the country began to migrate to Bolivar and Amazonas to work in the mines, became infected and then returned to their homes. This contributed to a huge increase in cases in this area, but also to the reactivation of outbreaks in other areas of the country,’ he says.

San Isidro, in Sifontes, perfectly illustrates the connection between deforestation due to mining expansion and the increase of malaria cases: between 2007 and 2017, it lost about 3,058 hectares of forest while malaria increased by nearly 746 per cent, according to a study published in Plos Neglected Tropical Diseases.

The same research revealed that most of those affected by Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum, the two species of malaria parasites prevalent in the area, were men engaged in mining activities.

Living on ‘dos gramas al día’

You don’t have to go far from the Troncal 10, which stretches more than 900 kilometres and connects with Brazil, to appreciate the changes to the landscape caused by soil removal for mining. Along the road, men and women carry on their heads the tools used to quarry the mud in search of the golden metal.

This is the daily work of 34-year-old Kemberly del Valle, who lives in Las Tres Rosas, in Tumeremo. Working in the mines she can collect ‘one or two gramas’ of gold per day. The grama, a gram of gold, is worth US$50 (£38.45). This income helps support her two children, especially her 15-year-old daughter, who is already the mother of a baby girl a few months old.

This amounts to a living wage in a country where the monthly minimum wage, at the end of March of this year, was equivalent to US$1.62 (£1.20), and 94.5 per cent of the population is living in poverty.

Kemberly works at the Pueblo Nuevo mine, an 8-hour walk from Tumeremo or a 40-minute flight by light aircraft. ‘I’m waiting to leave again, because here in Tumeremo, the situation is ugly,’ she says, referring to the difficult economic conditions in her town, where, as in much of Venezuela, services are charged in dollars.

Women are often victims of sexual exploitation or violence in the mines. But the threat that finally reached Kermberly was malaria, whose symptoms – fever, chills, exhaustion, and headache – she began to feel on 31 December.

At the Ministry of Health’s Francesco Vitanza field research centre, she receives the treatment she needs and an insecticide-impregnated mosquito net that she will take with her to the mines. Although this is not the first time that Kemberly has gone for malaria treatment, receiving the mosquito net is a novelty, a benefit of the humanitarian aid that has arrived in the area.

Malaria-control efforts need to be sustained

Malaria remains an emergency in Venezuela, but in 2020 cases dropped by almost half. A total of 232,000 cases were recorded, a change in trend that the WHO World Malaria Report attributes to ‘restrictions on movement during the Covid-19 pandemic and a shortage of fuel that affected the mining industry.’ The document also notes that confinement may also have affected access to health services, which would have led to a lower reporting of cases.

The biologist and researcher of the Central University of Venezuela, María Eugenia Grillet, points out that the decrease in malaria cases in the country can also be attributed to the work of NGOs to alleviate the precarious state of health services, affected by the country’s wider humanitarian crisis.

The International Red Cross, Doctors Without Borders, and the Rotary Club have worked with local authorities to implement preventive and palliative measures such as the distribution of medicines and insecticide-treated mosquito nets.

‘Simply by conducting surveillance and early diagnosis and administering treatment, transmission was interrupted, and cases dropped dramatically. Malaria, from the point of view of strategies and instruments, can be tackled. The problem is the situation in Venezuela, this mining chaos, this whole situation where a control program has to be developed,’ says Grillet.

Mining and violence

The figures on violence illustrate the scientist’s assertion. Two mining municipalities in the state of Bolivar account for the highest numbers of deaths due to violence in the country: El Callao, with 511 deaths per 100,000, and Sifontes, with 189 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. A report by the NGO SOS-Orinoco describes numerous massacres, extrajudicial executions, and disappearances as irregular armed groups and the Venezuelan army fight for control of the mines.

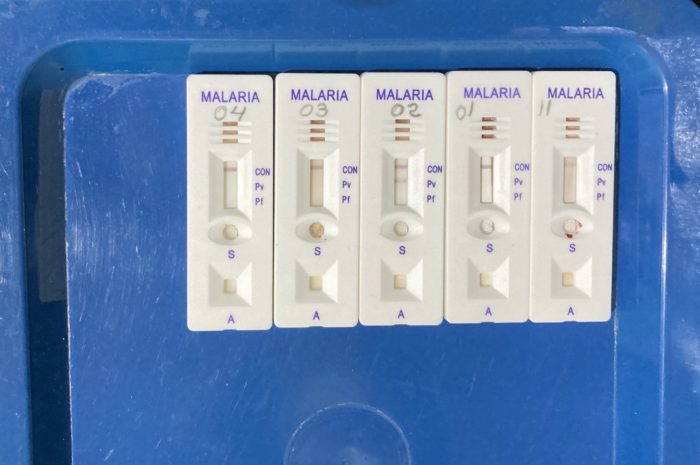

In the midst of this violence, 74 malaria diagnosis and treatment points have been installed in Sifontes, 40 by local health authorities, and 34 by Médecins Sans Frontières. The efforts have been directed mainly towards Las Claritas, in the locality of San Isidro, where much of the mining activity is concentrated, explains doctor Grecia Paz, coordinator of the NGO.

’The main measure is vector control, which ranges from mosquito nets to insecticides, depending on the habit of the transmitting mosquito that lives in the area’, Paz says.

The alliance with entomologists who monitor the behavior of the anopheles is fundamental to establishing preventive guidelines that may vary from one community to another.

In any case, it is still necessary to maintain the fight against malaria in Venezuela, especially in the mining areas, since the country, together with Colombia and Brazil, contributes 70 per cent of the cases in the continent.

In addition to the international humanitarian cooperation already present in the area, the Global Fund, an international alliance that fights against endemics, approved US$19 million (£14.5 million) for the period 2020–23 for the fight against malaria in the country. Local investment, however, remains precarious: the latest contribution from the Venezuelan government for the anti-malarial program was US$940 (£718) in 2018.

According to Gabaldón, without local investment and without rebuilding the permanent epidemiological surveillance system, which in the mid-20th century allowed Venezuela to be a global reference in terms of malaria control, it will be impossible to curb the spread of the disease permanently.

‘It is a mistake to think that when the disease is under control, that when cases go down, epidemiological surveillance measures should be completely forgotten. I would say that perhaps this is the main lesson that can be drawn from what has happened with the malaria epidemic in Venezuela’, he says.

Main Image: Gold mining has accelerated deforestation south of the Orinoco. Image: Jorge E. Moreno

This reporting project was funded by the European Journalism Centre, through the Global Health Security Call. This program is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.