It’s 11 January 2020, and I am sitting on a hot and unforgiving cement esplanade, at the commemoration of the 10th anniversary of Chile’s national Memory and Human Rights Museum. The mood is generally good natured, but somewhat restive: in between the official acts and speeches, the crowd spontaneously breaks into chants. These compare right-wing president Sebastián Piñera – whose approval ratings currently stand at an all-time low of only 6 per cent – to Pinochet, and unflatteringly accuse the police of being ‘lackeys of the state’ (although their language is more graphic).

The date marks almost 3 months since Chile hit the headlines for massive street protests. Sparked by a hike in public transport rates, the social unrest has morphed into a repeated demand for ‘dignity’, along with a denunciation of almost everything about working and lower middle-class life in one of Latin America’s most unequal, and nakedly neoliberal, societies.

Secondary school students have been at the forefront of the movement, adopting as their ‘patron saint’ a recently deceased street dog who became famous for fiercely defending students from the police. A bleakly catchy 1980s protest song about urban youth condemned to an empty existence has become one of the movement’s anthems, giving the lie to Chile’s relentlessly cultivated international image of stability and success.

Chile recently joined the OECD, and poverty and even inequality, severe though it is, have been on the decline in recent years. These hard, cold numbers seem however to have little purchase in the face of this hot, sometimes inchoate howl of rage.

Under the rainbow

So, what was the tipping point? What finally pushed a passive, politically jaded and undoubtedly individualistic population – or at least a visible and significant portion of it – beyond breaking point? Columnist Daniel Matamala’s answer – the vanishing of the horizon – makes sense, at least to this author. As the long and bloody Pinochet regime drew to a close in 1990, Chileans were promised rainbows. What they got was a softly-softly, business-as-usual arrangement – now routinely, and usually pejoratively, referred to as ‘el modelo’. The ‘model’ left untouched most of the profound constitutional, institutional, economic and cultural changes wrought by 17 years of military rule.

The dictatorial regime, sometimes more, sometimes less, ideologically neoliberal, but always fervently authoritarian, left legacies that no subsequent administration dared or managed to unpick. The most extreme include a widely-reviled compulsory personal pension system that generates billions for its financier owner-administrators, and quite literally almost nothing for the great majority of its users.

Most bizarrely of all, the military enshrined in the constitution a clause which commodifies Chile’s once-abundant reserves of water. The state is empowered to grant exclusive user rights, free of charge and in perpetuity, to private actors. The result can be clearly seen in aerial photos that show avocado-growing agribusiness reserves, startingly lush and green, amongst the parched valleys of the drought-stricken north, rapidly returning to desert. Water to keep avocados lucratively landing on the breakfast tables of Europe is diverted, dammed and usurped by its private owners. No legal or regulatory instrument exists that can force them to take heed of those who live downstream: decade-long efforts to have water declared a public or common resource were recently voted down in the Senate. The key vote was actually strongly supportive of the move (by 24 votes to 12, but Chile´s sui generis requirement for two-thirds-plus-one supermajorities for constitutional change means that for these purposes, 12 votes trump 24: the margin was not sufficient to see the reform through.

El baile de los que sobran

The litany of the neoliberal right’s real and perceived perfidies is a long and detailed one, but the specific content of the list perhaps matters less than the cumulative sense most ordinary people have, of being on the receiving end of utter disdain from a patrician ruling elite that regards them as lumpen or as rotos: the undifferentiated, uncouth masses. A whole string of scandals over big business collusion, clerical abuse, police and military procurement scams, and illegal political campaign finance have added to the sense of profound disillusion and indignation, righteous or otherwise.

It is hard to overstate the profound sense of living in a country that has lost all sense of the public, the collective, or the need to steer towards a common destiny. It is similarly hard to detect any vestige of a social glue that could reward public-spirited behaviour on the part of the haves. The have-nots, or have-less, may finally have had enough.

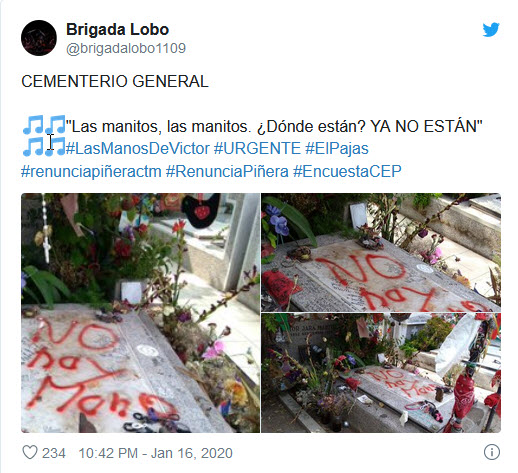

This anomie has its sinister side: far right anti-immigrant rhetoric and violence is as palpable among the poor as among Chile’s unashamedly xenophobic well-to-do, and memory sites commemorating victims of Pinochet-era human rights violations have been vandalized and defaced with swastikas during the recent unrest.

Protests have also provided a perfect cover opportunity for looting and other manifestations of poor-on-poor exploitation. There is, however, much to celebrate about the recent explosion of resistance – from its determinedly carnivalesque air, and creative, verbally dexterous slogans and memes, to its feminist and anti-colonial strands, and clear yearning for re-encounter, including between the generations.

The tin ear of authority

This strong desire for lost human connection was perfectly illustrated in Santiago on New Year´s Eve. So too was the inept response of political authorities, who have acted throughout with a mixture of insouciance, tone-deafness, and heavy-handedness. First it was announced that official New Year celebrations would be called off. Next, the city’s public transport – traditionally extended on New Year’s Eve – was instead ordered to shut down early. Unofficial fireworks and impromptu street parties would not, we were told, be happening; while police threatened to simply occupy, by sheer force of numbers, the city square that has become the Ground Zero of the protests.

In the event, nothing could have more graphically demonstrated either the authorities’ undignified and undemocratic fear of people occupying public space, or the fact that city authorities are simply no longer in charge. Dozens of people calmly showed up in the square in the early afternoon, busily setting up trestle tables and preparing to serve hundreds of portions of free food through the night. First aid was provided by unofficial brigades of paramedics, now a permanent fixture around the square thanks to weekly pitched battles between protesters and heavily armed police. A cordon of self-appointed ‘front line warriors’ kept a watchful eye on police front lines (the ready adoption of military metaphors on both sides is both striking and disturbing). Miraculously, the police acted prudently for the first time in weeks, retiring to a discreet distance.

The largest, best-natured and most euphoric street party since perhaps the end of the dictatorship promptly got under way, prolonged by the authorities’ self-defeating strategy of leaving attendees stranded, without transport, in the city centre. Around 100,000 people, many of them families with young children, simply partied until dawn.

Systematic police brutality

Throughout the whole period of the protests, police special forces have behaved with spectacular and jaw-dropping disregard for public safety, basic discipline and simple effectiveness. They have partially or fully blinded dozens of protesters by firing tear gas canisters at head height into crowds; deployed supposedly ‘plastic’ shot pellets actually made of much more dangerous materials; and been caught on camera laying indiscriminately into protesters, onlookers and passers-by alike.

One young man was deliberately run over by an armoured car, in full view of hundreds of protesters, breaking his pelvis and leaving him with life-threatening injuries. Another, student Gustavo Gatica, has become a byword for the senseless and unnecessary human cost of bellicose policing, after losing both his eyes to the impact of randomly fired ‘plastic’ pellets. The deeply distressing image of this slightly built and lost-looking teenager, seated on the pavement with blood streaming from both empty eye sockets, being comforted by an unknown passer-by, will surely haunt the memory of all who saw it.

The corrosive effect of all of this on police legitimacy, particularly in the peripheral urban poor communities where violent, repressive policing has long been the norm, will be felt for generations to come. It is impossible to discern any vestige of understanding of the need for consent-based policing in the defiant subsequent declarations of the national police commander. He asserted that he would permit no officer to be disciplined or dismissed, no matter what they were later proved to have done.

A steady stream of national and external monitoring reports painstakingly documenting repeated human rights violations were simply dismissed, refuted or ignored, until mounting pressure forced a belated nominal suspension of some of the worst police tactics. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights carried out a preliminary visit in November, and an official visit in late January and early February 2020 will investigate the situation further. This abusive, repressive, reaction, and the clear failure of guarantees of non-repetition that it represents, is perhaps the most dismaying aspect of the events of recent months.

Those who see this as the wheels finally coming off the neoliberal bus are not entirely mistaken, though the expectation that it must or will lead to real change are being sorely tested. Chile’s widely discredited political class – left, right and centre – wasted no time in recreating what sounds to many like the same appeal they heard, and naively heeded, back in 1990: go home, simmer down, and defer to the experts. Every apparent concession from a woefully out- of-touch ruling class has been withdrawn or diluted when the time came for the small print to be hammered out.

The promise of a new Constitution – consistently sought since 1990, and just as consistently denied – is no exception. A plebiscite is now due to be held in April 2020, to determine whether a replacement will be crafted at all, and if so, how. The options have however been pre-emptively limited to exclude the ´constituent assembly’ option – considered too emotively radical – sticking to alternatives more susceptible to control by the existing political class. A proposal for gender parity in the constitution-drafting body was blocked by the same peculiar 12-24 minority mentioned above. Mainstream and far right-wing parties have already come out against the whole idea of replacement, making something of a mockery of their claims in the early weeks to have ‘understood the message’ of popular discontent.

Meanwhile, record temperatures in the capital and the onset of the summer holiday period, when the capital and other major cities traditionally empty out, have muted the protests for the time being. Many however expect that March will see fresh waves of activism and heavy-handed reaction.

For more information:

Recently published report on truth, justice and memory in Chile, including discussion of inequality and ECOSOC rights violations as unaddressed consequences of dictatorship-era repression:

Observatorio de Justicia Transicional, Universidad Diego Portales (2019) ‘Memory in Times of Cholera: Truth, Justice, Reparation and Guarantees of Non-Repetition for Dictatorship-Era Human Rights Violations’, for version in English click here or here, and for the original text in Spanish, here

Other chapters in the same report, covering labour, education, and indigenous rights among other issues, in Spanish, are here.

Reports on the human rights dimensions and implications of the recent protests:

In English and Spanish:

Human Rights Watch (2019) ‘Chile: Police Reforms Needed in the Wake of Protests: Excessive Force Against Demonstrators, Bystanders; Serious Abuse in Detention’ 26 November 2019 ; ‘Chile: Llamado urgente a una reforma policial tras las protestas: Uso excesivo de la fuerza contra manifestantes y transeúntes; graves abusos en detención’ 26 de noviembre de 2019

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (2019) ‘IACHR Condemns the Excessive Use of Force during Social Protests in Chile, Expresses Its Grave Concern at the High Number of Reported Human Rights Violations, and Rejects All Forms of Violence’ 6 December 2019, Press Release Ref 317-19 ; ‘CIDH condena el uso excesivo de la fuerza en el contexto de las protestas sociales en Chile, expresa su grave preocupación por el elevado número de denuncias y rechaza toda forma de violencia’, 6 de diciembre de 2019, Comunicado de prensa ref. 317-19.

In Spanish only:

Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos, INDH (2019): Informe Anual Sobre la Situación de los Derechos Humanos en Chile en el Contexto de la Crisis Social.

Amnistía Internacional Chile (2019) ‘Chile: Política Deliberada Para Dañar A Manifestantes Apunta A Responsabilidad De Mando’ 21 de noviembre de 2019